I can’t quite remember the first time I encountered Texas Isaiah’s images but they have imprinted on my mind, wedged in like a bookmark, ever since. His images of Black people, particularly of young Black transmasculine people in nature, always seem to find me at the right moment in life, conjuring up warm possibilities.

When I caught up with the Brooklyn-born photographer, who now splits their time between New York and Los Angeles, over the phone in February, they had just returned home from a late night out at Papi Juice, a party run by an artistic collective of queer and trans people of color. Nightlife is where Texas Isaiah first started experimenting with the camera, before shifting his gaze from the undulating throngs of bodies in the club to the quietude of portrait sessions with his “sitters,” a term he borrows from painting.

In 2020, the Black transmasculine artist was heralded as the first trans photographer to shoot for the cover of Vogue and Time magazines, capturing images of notable Black movement makers including Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors, writer Janet Mock, retired NBA player Dwyane Wade, and actor Gabrielle Union. While Texas Isaiah may be a first for Vogue, they don’t consider themselves to be an inaugurate. Instead, Texas Isaiah says they’re part of a “Black trans renaissance” and notes the historical erasure of artworks and practices by their Black trans ancestors who didn’t have the same resources or platforms to be considered by the mainstream.

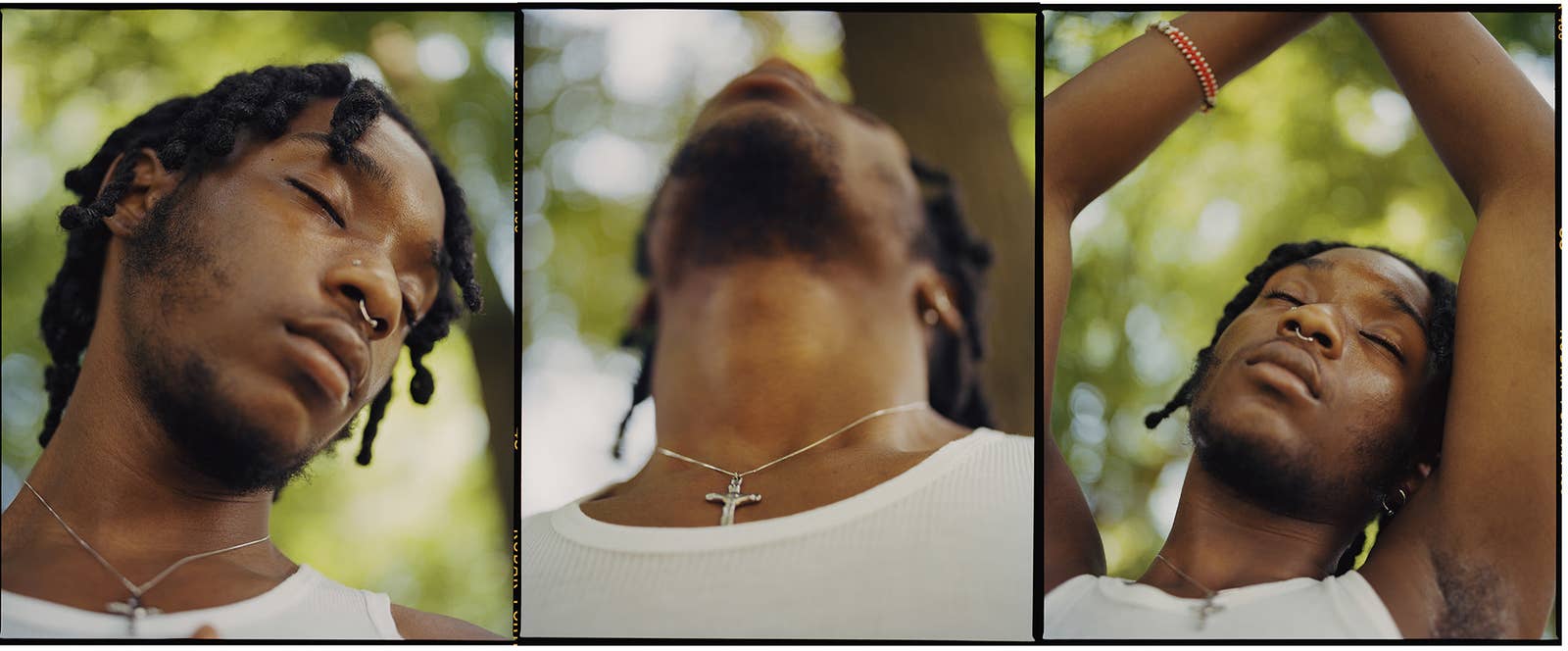

His multiyear project Flowers at Your Feet memorializes and celebrates Black transmasculine life. Texas Isaiah first thought to start this project in 2019, and began collecting portraits during a yearlong residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem between 2020 and 2021. Today, the project is in its second chapter, with a heavy focus on the question of the Black transmasculine dream, its texture, and what our dreams say about our desires.

I spoke with Texas Isaiah about the importance and urgency of creating a transmasculine archive and the limits of representation amidst a growing climate of anti-trans and anti-Black legislation. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you come into photography and what was your first experience with a camera?

My first experience with a camera happened when I was part of nightlife in New York City. I took a lot of images at events and parties. I ventured into live performance photography and then I took a break. I took some time to figure out what kind of work I wanted to make.

I didn’t really speak about my gender transition publicly a lot but during that time [in 2013 and 2014] the media was coining that era as the “trans tipping point.” There was so much uncertainty for myself and around how I’d be able to live and exist. I took a lot of time to ground myself and that’s where my relationship with portraiture emerged.

What drew you to portraiture specifically?

I was interested in developing a more concrete archive because I had lost a significant amount of people in an eight-month period. People from childhood had passed away, my coworker, and the last person was my grandfather.

Looking back, I didn’t have a visual archive of these people. I just had my memories, and there was a visual loss that resonated with me deeply. I started to think more about what it would look like to contribute to an everlasting archive. Black and brown POC trans people weren’t being imaged a lot during that time, so I thought about the ways I can do that differently that weren’t immediately tethered to media or traditional aspects of representation.

Can you say more about the importance of creating a specifically Black transmasculine archive? It’s not something that’s just going to appear unless somebody goes out and creates it. Do you feel a certain responsibility in that work of creating an archive?

When I was creating the archive, which was Black trans people in general, I didn’t feel a full connection with a lot of the [other trans-centered] work that was being created, especially of just masculine people in general. There are so many reasons why there isn’t a lot more Black trans representation in the media. It was not so much that I wanted to be seen, actually. I wanted to be able to extend space to people who felt invisible, who felt that they didn’t deserve to be imaged. When we look at media, the transmasculine people that are popular and who are extended resources are white transmasculine people.

It’s so important for people to see themselves so that they are able to heal and grow from the things they’ve been taught. There is so much that is projected onto us, and the reality is that we haven’t always been in proximity to the most healthy terrains of masculinity. But I believe that Black transmasculine people — in the ways that we have cared and loved throughout history and today — are really shifting the perspective of what it looks like to be a person of good character who is also masculine.

I think for myself as a Black transmasc person, who is being perceived more and more as a masculine person, it’s hard to find the words for the specificity of these experiences. What do you think that specificity is, or the uniqueness of it, that is missing from representation? And how do you characterize that in relation to those you photograph?

The beautiful thing about Flowers at Your Feet is that it mostly highlights transmasculine people, which includes trans men. I think that there is so much nuance there because not everybody has the same relationship to their masculinity — not everybody identifies as a man.

And I’ve learned myself that other people desire specificity. I don’t need that for myself because I don’t think that there is always language to describe our existences, and I’ve made peace with that. Those gray areas are really beautiful to me, because that means that I don’t have to lock myself into something that I may grow out of. There’s such a deep desire to keep that open.

Inherently, I view transness as, like, such a deeply spiritual space. I believe that, you know, the spirit doesn’t have to have any specificity. I think that’s such a beautiful thing.

Where did you come up with the name Flowers at Your Feet? What does that mean in relation to the orientation of the project?

It was something that someone I dated a long time ago used to say to me. I asked them, “What does that mean?’ They said, you know, ‘I’m just giving you your flowers. I’m offering you gratitude.’” And when I was thinking about a Black transmasculine archive, and also the masculine archives that exist today, it was during that era where people were creating a lot of images of Black masculine people and flowers.

That was so beautiful aesthetically, but I don’t think that conversation went as far as it could have. I think it stopped at aesthetics. I decided to use that title for the project to offer my gratitude to Black transmasculine people — past, present, and future — but also to contend with the images made at that time. There aren’t any flowers within the images I make; the flowers are the Black transmasculine people themselves.

A lot of people mention the kind of care and consent you cultivate with the folks you photograph. Do you see photography as a form of care work, or like healing work?

The care practice first and foremost has to begin with how I am in relationship with people interpersonally. That extends into the work because the beginnings of photography — and it still continues today — but there has been a lot of historical violence that people have imposed onto communities through a camera.

It involves conversations with people and how they feel about being imaged. Do they feel worthy to be imaged? What kind of visual archive, what would they like to see today, and how can they be a part of that?

There’s also this aspect of the care that I like to extend after the image is taken, which looks like asking people if they would be open to the images being publicly displayed, if the works are in a gallery or a museum setting. I made sure that the sitter gets a percentage of work sold, you know, just sort of bringing back money into the community.

There’s a good percentage of my work that nobody has seen. Somebody hired me to photograph their birthday, or I’ve imaged people for their top surgery anniversaries, and you know, those images are for them. I think that’s also a type of care too, because sometimes with creating images, photographers feel like they have a right to display whatever they want without consulting their sitters.

I don’t believe that. For me, making images is all for the person, ultimately. It’s really vulnerable work.

Do you see yourself as creating history, or creating a possibility or a future within this archive of Black transmasc people?

You know what’s so funny about this question? I feel like people are mostly compelled to say no, and if you had asked me this like five years ago, I would have said no. But yes, yes I am. We need to be honest with that. But I’m not the only one that’s doing that. I’m surrounded by brilliant Black trans people. I’m not alone in it, but yes. I feel like you’re also creating history, as a journalist, as a Black transmasculine person who works at BuzzFeed — like we need to be very honest about that, because it’s not our fault that we have to name those things. There is history being made and it’s a beautiful thing. I’m so honored to be part of the conversation and to contribute.

With all of these anti-trans bills and all of these bills targeting education, specifically the Black queer history in school and the ability to learn that and access that — do you feel like the stakes are high in your work? And at the same time knowing that representation can sometimes be a trap, how do you think and juggle all of those things?

When the quote-unquote trans tipping point developed, there was a huge urgency for me to create images, because I know that people would try to trap us in representation and media and the delusion that we’re on the red carpet, so that means our communities are well fed and thriving when that’s the complete opposite of what’s going on. The urgency has always, always been present.

There is so much more work that needs to be done outside of being in front of the camera. This moment is really difficult but the young folks out there, in their teens, early 20s, are so amazing and powerful and deeply convicted.

I remember I went to Tallahassee for an assignment with Atmos and they interviewed people about climate change who were between the ages of like 18 and 24. I was so inspired, because there was legislation popping up in Florida but they were like, “We’re going to get access to the information that we need by all means necessary.” I wish it wasn’t like that, and I wish that they didn’t have to think that way, but that faith is so important to have in this world.

It’s so important for me to make this work right now because I want images of Black trans people to exist where we are at rest, where we are laying in the grass and having a moment to ourselves. I want those archives to exist alongside other archives that people desire. Whether or not people are seen in cinema, in editorial, in commercials — those should exist of course — but I wonder about images that speak to our lives and our dreamscapes, the livelihoods that we deserve.