As COVID slowly exits the epidemiological limelight (but is still very much here to stay), outbreaks of another icky germ — norovirus — are making a comeback and returning to prepandemic numbers.

Commonly known as the stomach flu, "cruise ship virus," food poisoning, or stomach bug, norovirus is the kind of germ that you never forget if you (and likely all your family and friends at the same time) experience its symptoms. It is an extremely contagious pathogen that causes acute gastroenteritis, or inflammation in the stomach or intestines, resulting in intense bouts of diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, and nausea. Symptoms can last up to three days and can also include headaches, fever, and body aches in some people.

Even though it’s sometimes called a stomach flu, it has nothing to do with influenza, the respiratory virus that comes in waves every year. There’s no vaccine for norovirus.

The bug seems to be making brutal rounds in the Northeast, particularly New York City, sentencing people to their toilets for a few days. The CDC reported that norovirus cases are rising nationally as well. The UK is also experiencing the highest norovirus levels at this time of year in over a decade.

While it may seem like the germ is bringing more people down than ever before after a three year break from everything non-COVID, a CDC spokesperson told USA Today that cases “remain within the expected range for this time of year.”

Contact with contaminated poop or vomit particles may get you sick, and that can happen while sharing eating utensils, consuming meals or liquids prepared by an infected person, or changing a diaper, for example. While norovirus affects people of all ages, children under 5 and adults 65 or older are more likely than people in other age groups to come down with serious symptoms.

The bug latches on to about 20 million people every year in the US, causing about 900 deaths (mostly among adults ages 65 and older) and about 109,000 hospitalizations.

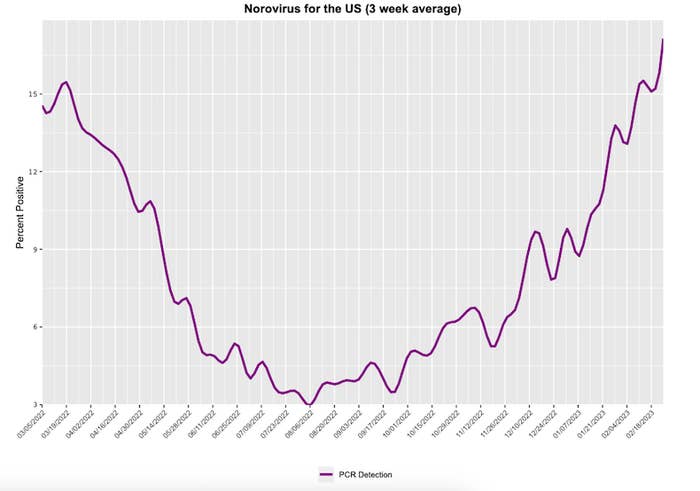

After a quiet 2020 and 2021, likely because of COVID preventive measures that forced many other viruses into hiding, norovirus made a rapid return beginning in January 2022, according to data from 12 state health departments published in September. The number of reported outbreaks in the 2021–2022 surveillance year was nearly three times that of 2020–2021.

“I think a lot of folks have forgotten that other viruses are around these days, but norovirus is still here,” said Anita Kambhampati, CDC epidemiologist and lead author of the report. “So this is just a reminder that we are seeing that return to prepandemic levels.”

Between August 2021 and July 2022, 992 norovirus outbreaks were reported to the CDC, compared with 343 in the previous surveillance year (when COVID dominated the virus landscape) and 1,056 the year before that. For further comparison, there were about 1,200 and 1,400 reported norovirus outbreaks from 2015 to 2016 and from 2018 to 2019, respectively.

Most of the outbreaks (59%) included in the September report occurred in long-term care facilities, which isn’t unusual, Kambhampati confirmed; the prepandemic range was between 53% and 68%. Norovirus typically makes its way into healthcare facilities through infected patients, staffers, visitors, or contaminated foods, and outbreaks sometimes last months.

Outbreaks are also common in schools, dorms, restaurants, childcare settings, and cruise ships — places people share dining areas and close living spaces.

Norovirus generally spreads easily where there’s a lot of close person-to-person contact and little access to hand hygiene, including outdoor activities. In fact, outbreaks have been documented in the Grand Canyon National Park following backpacking and river rafting trips.

The largest norovirus outbreak there started in April when seven people in a commercial river rafting group experienced vomiting and diarrhea, according to a CDC report. By June, at least 222 rafters and backpackers in the area had come down with a suspected norovirus infection. Swabs of portable toilets used by the river rafting groups tested positive for the germ.

The good news is that the norovirus circulating in the population is behaving as expected and isn’t showing any signs of mutating into more serious versions of itself, Sara Mirza, CDC epidemiologist and coauthor of the new report, told BuzzFeed News.

“At least that’s not what the data we’ve seen yet have shown us,” Mirza told us in September. “But it’s something we’re monitoring.”

The same norovirus strain that has been spreading this year first emerged in 2015, and it makes up a large portion of the new cases.

“We’re definitely expecting to see a return to more of our traditional norovirus season,” Mirza said. The US is already seeing other viruses, especially those that affect the respiratory tract, making comebacks as well.

How to avoid getting sick from norovirus

Norovirus outbreaks can happen anytime, anywhere, but they tend to surface between November and April, when more people gather indoors to escape colder temperatures. This means hand hygiene is particularly important during the holiday season, when you might share meals and utensils prepped and set up by others.

A person usually develops symptoms 12 to 48 hours after exposure, and most people recover within one to three days. As few as 18 viral particles are needed to make a person sick, the CDC says. Infected people shed billions of these particles in stool and vomit while symptomatic and can continue to do so even when they feel better. Feces can carry norovirus for over two weeks after a person has recovered.

So you may want to be extra cautious if you share a bathroom with someone who is sick. Norovirus particles can become aerosolized when a toilet that contains contaminated vomit or diarrhea is flushed, so closing the lid is a good idea, Kambhampati said.

Projectile vomit, which is common with norovirus, can also cause aerosolization.

Norovirus is not a respiratory germ, however, so wearing a face mask isn't the best way to avoid infection, Kambhampati said. But wearing a simple one in situations where you may be cleaning up after someone who is infected can help you avoid touching your mouth or inhaling droplets.

The virus can survive on a variety of surfaces, such as countertops and serving utensils — and in water — for up to two weeks. It can even remain infectious on foods at freezing temperatures and those above 140 degrees Fahrenheit.

And probably worst of all is the fact that norovirus resists many common disinfectants and hand sanitizers, so the absolute best way to avoid infection is to wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially before and after you eat and after using the bathroom. (In the case of the outbreaks in people who were rafting, hand sanitizer wasn’t enough to kill the germs.)

Generally, it’s a good idea to avoid touching your face (especially your mouth) in public.

If you’re caring for a person with norovirus, experts recommend wearing a simple mask and disposable gloves when cleaning the areas they touch and use. Start by wiping all contaminated surfaces with paper towels and spraying a bleach-based cleaner, letting it sit for at least five minutes. You should then clean the entire area again with hot water and soap. It’s a good idea to then put the sick person’s clothing in the washing machine, take out their trash, and wash your hands.

Unfortunately, you can get norovirus multiple times because different strains can infect you. While you do develop some immunity to specific types of norovirus after infection, experts don’t yet know how long that lasts.

No treatments exist for the virus, but with consistent hygiene and plenty of fluids (repetitive vomiting and diarrhea can lead to dehydration), you’ll be on your way to recovery.

UPDATE

This story has been updated with new details about increasing norovirus cases in 2023.