“Look, Jose,” the cop said to the genial grandfather sitting across the desk. “The fact is, you’re being charged with murder.”

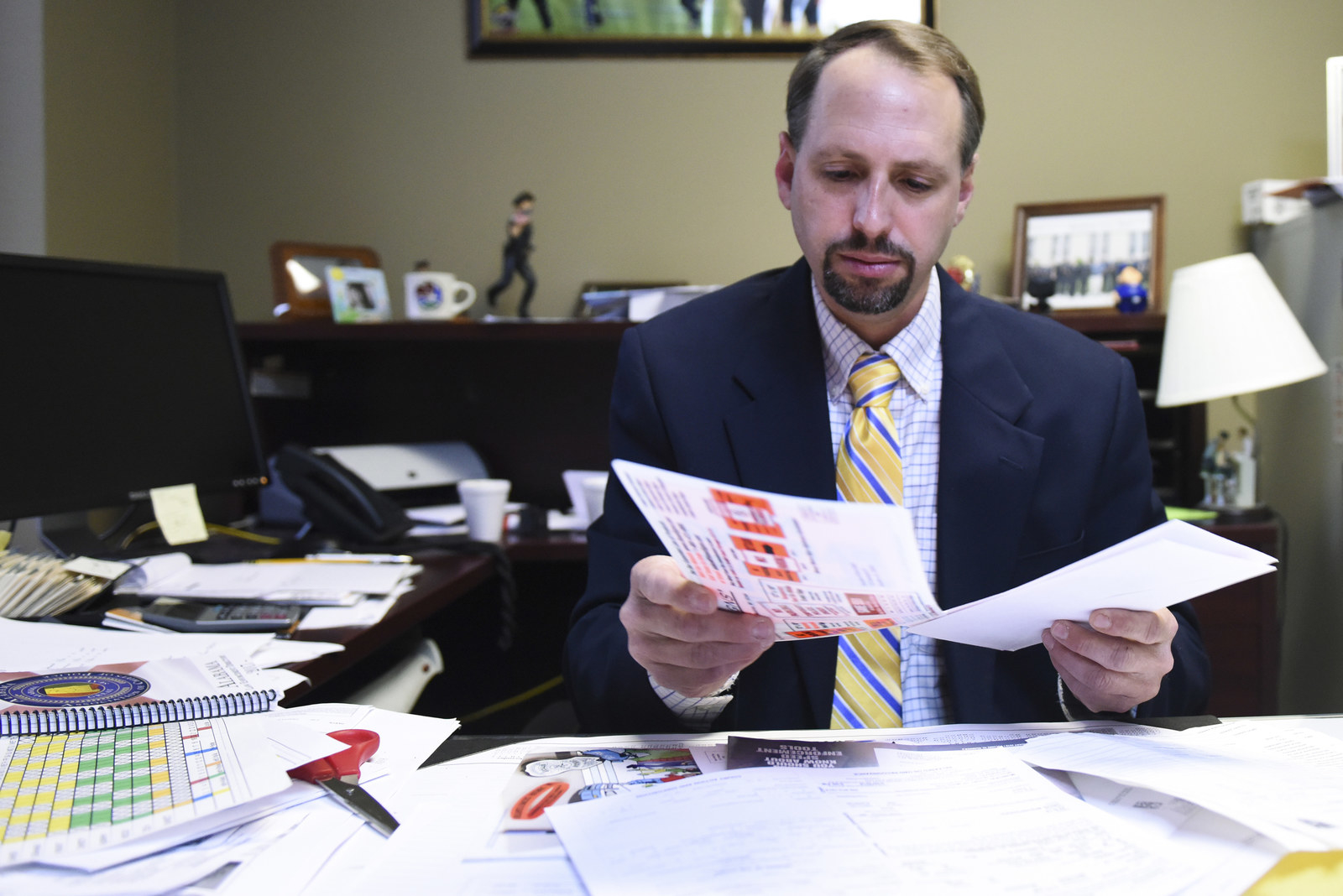

Tim McWhorter, the chief investigator for the Lawrence County Sheriff’s Office in rural Alabama, was reaching. He had very little to tie Jose Manuel Martinez — a soft-spoken man with an easy smile who’d spent much of the last few months playing soccer and make-believe with his grandchildren — to the bloody body of a young man found in a nearby hayfield.

But Martinez seemed to make a decision. “You guys have been real respectful to me, and I appreciate that,” he said. “Do you want me to tell you the truth?”

McWhorter nodded.

“Yeah, I killed that son of a bitch.” Martinez’s eyes, which McWhorter had found so friendly moments before, were now black and cold. “He said some bad stuff about my daughter. I stand up for my family. I don’t let anyone talk about my family.”

McWhorter was still trying to make sense of that when Martinez delivered a much bigger revelation: “I’ve killed over 35 men in my life.”

Martinez, who was born and spent most of his life in California, said that for three decades he had worked as a gun for hire, collecting debts and killing people across the United States. Police say that work was often for Mexican drug cartels, though in a few cases he also killed people just because they pissed him off. Martinez refused to say anything about the drug business, including whom he worked for or with. But he was more than happy to talk about bodies. And about his own prowess in killing. They called him El Mano Negra, he said — the Black Hand.

The dead were young and old, drug dealers and farm laborers, fathers and husbands. But always men. They were scattered across as many as 12 states, but his primary killing ground was Tulare County, a little-populated land of vast green fields and listless, sunblasted farm towns in California’s Central Valley, where Martinez had been born and raised.

“You want to know who killed them all?” he asked at one point. “I killed them all.”

And they deserved it, he said, because in addition to whatever else they’d done, he claimed that many of them had abused women or children.

With a lethal professionalism, Martinez set up a fake traffic stop or a false business front or hired honeypots who lured men to lonely places. Then he killed, often with a bullet to the head. Afterward, he collected his money and slipped back into his quiet, unassuming life, taking his children to Disneyland and on other adventures. “Good parents take their kids camping,” he told police officers.

It was for his family, Martinez said, that he had chosen just days before to leave the safety of a glorious beach on the Sea of Cortez, where he had been enjoying himself with a cold Corona and a beautiful young woman. He had heard that police intended to question one of his beloved granddaughters about the dead body in the hayfield, and he couldn’t bear the thought of it. “My family don’t have to pay for any of the stupid things I done in my life,” he insisted.

His story seemed fantastical, but he urged McWhorter to call around. It turned out that Martinez had been suspected of involvement in plenty of murders, though he had never been charged. After months of investigating on the part of police officers from at least three states; after consulting Martinez’s hand-drawn maps of where he dumped bodies; after marveling that he remembered the number and caliber of each bullet he fired, the angle and repose of each fallen victim — detectives from departments across the country decided it was true.

“Holy crap,” was how McWhorter put it. “We have caught an evil man.”

It was a long time coming. Martinez maintains he was able to go for decades without getting caught because he was “so damn good” at killing, and because so many police officers are “so stupid.”

Police in the Central Valley say they failed to catch Martinez because he is a smart and remorseless sociopath, expertly dispatching victims he had little connection to and leaving behind little in the way of witnesses or evidence. Kavin Brewer, a homicide detective in Kern County, California, calls him “the best I ever heard of, in my 35 years of law enforcement.”

Some in the small California towns where Martinez lived and committed so many of his murders offered an additional explanation: Life is cheap here, and the people Martinez murdered and the communities where they came from, with their transient populations of impoverished, often undocumented farmworkers, didn’t count. Drugs and money pound through this part of California in ceaseless, violent streams, but many towns don’t even have police stations. Patrols, when they do come through, don’t tend to develop deep ties to communities.

That he killed so many for so long suggests a dark truth about law enforcement in the US: Kill the right people — in his case, farmworkers and drug dealers, few of whom had anyone to speak on their behalf — and you just might find there’s no one to stop you.

PART 1: “THINKING OF ALL THE BAD THINGS I DONE IN LIFE.”

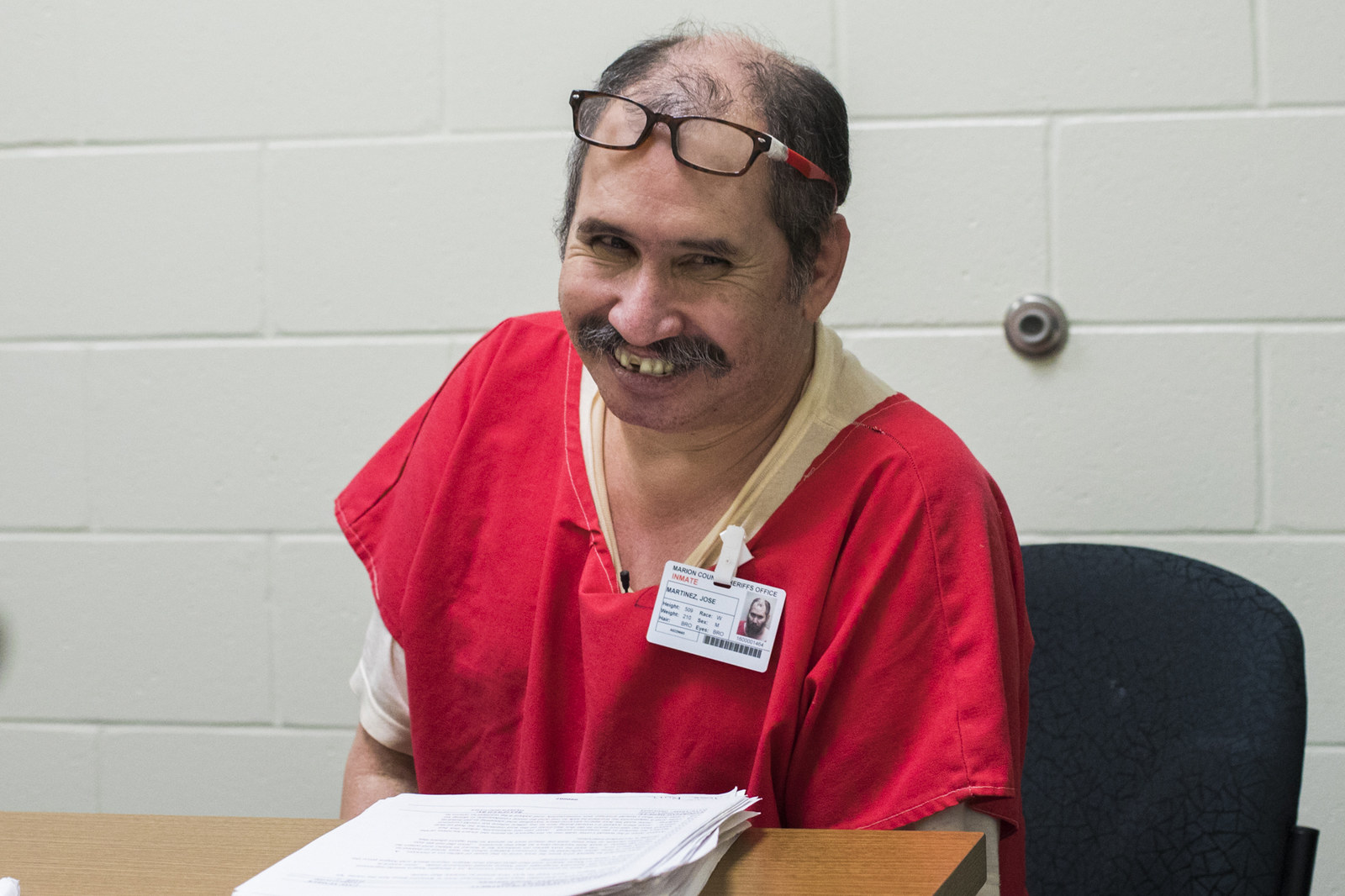

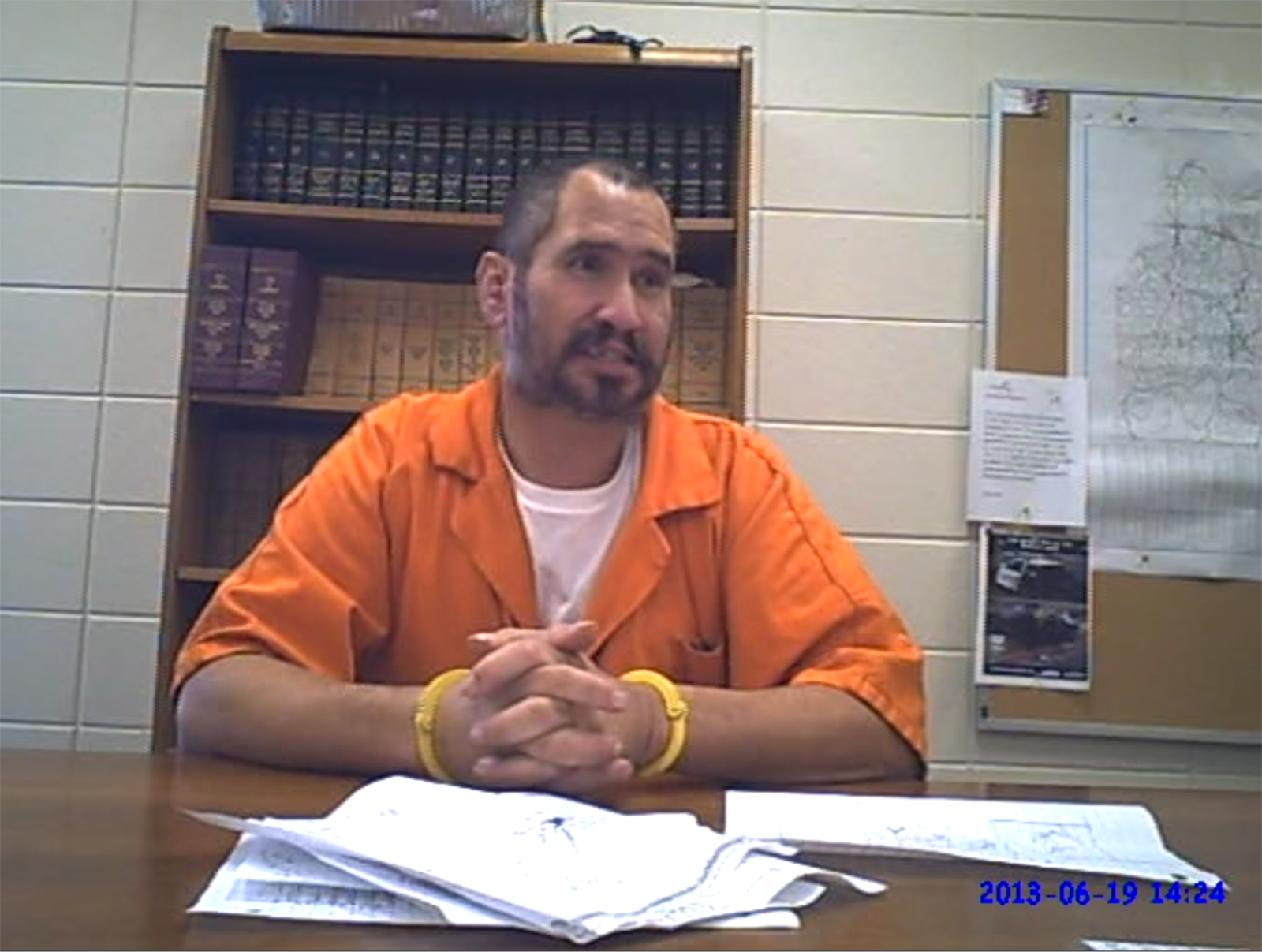

Martinez pleaded guilty to the murder in the Alabama hayfield. He went on to plead guilty to nine other murders in California, for which he was sentenced to multiple life terms. He’s now in a county jail in Ocala, Florida, awaiting trial for the murder of two construction workers whom he conned into thinking he was going to hire them. Florida prosecutors decided it was worth bringing him to trial in Florida, one was quoted saying, because they think they can have him executed. Martinez’s trial is set to start next year, and he expects to be put to death. “It doesn’t scare me,” he said. “I should have been dead a long time ago. I mean, a long time ago.”

Awaiting his day in court, Martinez, who has a round, friendly face and a frequent smile, remains courteous and solicitous. The guards assigned to him in jail say he is a model inmate. He listens to people when they talk, and nods and laughs at all the right moments. Moreover — as many cops have noted with appreciation — he is funny, a witty, wry observer of the world around him.

Sitting in his cell, he writes to his beloved granddaughters and other family members, dispensing advice and showering praise. He has also written his life story, twice. He suggests headlines for this article, including, in one letter over the summer: “True Evil has a face you know and a voice you trust. El Mano Negra.” He also revealed that he has done research on me and my editors, even obtaining a photo of us, which he keeps in his cell.

He reads almost anything he can get his hands on, including crime books and romance novels by Danielle Steel. And he writes love letters, such as a two-page missive to Melania Trump. “I don’t care if I get a federal charge for loving a woman,” he explained. “I’m very, very good to do love letter. I mean real good.”

Occasionally, he appears despairing. “I remember when I was a free man,” he wrote in a recent letter to BuzzFeed News. “I had everything, girls, money, guns drugs, Power, freedom, now i don’t have shit. Only this 8x12 cell where I spend most of my day doing love letters and thinking of all the bad things I done in life.”

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

Some of those bad things may only now be coming to light, after BuzzFeed News pored through cold cases in places around the country where Martinez said he killed people, identified those that fit Martinez’s patterns, and then set out to determine if he was the killer. Many of the cases had sat unsolved for years or decades — during which Martinez continued killing, depositing more bodies in more lonely fields. After BuzzFeed News began making inquiries, at least one homicide detective flew in from Oregon to question Martinez in his Florida jail.

Born and raised in a state notorious for its fascination with serial killers, Martinez was, by the numbers, one of the most deadly. His claims put him on par with the Night Stalker, Ted Bundy, and John Wayne Gacy — and far above the 12 now attributed to the Golden State Killer, whose recent arrest sparked nationwide headlines.

Yet catching Martinez fell to a small sheriff’s office in Alabama. McWhorter, its chief investigator, had followed his father into law enforcement right after high school and had never lived outside his tiny northwestern corner of the state. His department was so unprepared to investigate a drug-world contract killer that to interview one of their suspects, they had to call in the high school Spanish teacher and football coach to translate for them.

But that tiny department did what dozens of police in more sophisticated and well-funded departments across the country had for so long failed to do: It brought to justice one of the deadliest hit men in modern American history.

Martinez has confessed to more murders in California that have yet to be solved. He claims to have committed additional homicides in 11 other states: Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Missouri, Colorado, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Iowa, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

But the response to Martinez’s confessions mirrors the response to his crimes: Few seem to care that much. Even now, five years after his stunning admission, he is barely known outside the tiny, dusty towns where he struck terror, leaving families bereft and searching for justice. And law enforcement around the country has made little apparent effort to account for most of the murders he’s bragged about committing. While stories of the gruesome actions of cartel-backed assassins have made headlines across Mexico and in border cities, Martinez’s confessions appear to have sparked little concern about cartel contract killers sowing violence across a wide swath of the United States.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” said Gene Mitchell, the sheriff of Lawrence County. Martinez, he said, is “saying a lot of stuff that ought to be interesting to law enforcement.” He added: “How many other contract killers could he have given them? He probably knows them.”

Indeed, Martinez told BuzzFeed News: “I know three guys that — shit, one done about 30-something murders.” He gave no details.

After Martinez began confessing, McWhorter said he dutifully reached out to places where Martinez said he left bodies, to try to interest detectives in combing through their cold cases.

He didn’t get a lot of takers, he said. One officer in Seattle, McWhorter recalled, just laughed at him and said, “Yeah, we’ve had 25 murders in the last six months.”

PART 2: BECOMING EL MANO NEGRA

About halfway down California’s long Central Valley, as the peaks of the Sierra Nevada march upward toward Mount Whitney and the tule fog mixes with hazy smog blown up from Los Angeles, Tulare County feels like a place the 21st century has passed by, and maybe the last half of the 20th, too. Life here in California’s second-poorest county moves with the rhythm of planting and harvest; cellphone coverage is spotty; and most social life is rigidly segregated between rich and poor, white and Latino. South of Visalia, the county seat, a series of sleepy hamlets — Earlimart, Pixley, Richgrove — appear down Highway 99 like scattered remnants of California’s agrarian past.

Martinez was born near here, in Fresno, in 1962, to farmworker parents from Mexico. His choices, like those of the people he would eventually kill, were constricted and warped by the brutal limits of this place and that era.

About 40% of the fruits and nuts grown in the United States are harvested here. These towns, which may have begun as optimistic centers of commerce, with banks and mercantile stores, have faded into isolated, dusty settlements, some barely more than labor camps for migrant workers. There are few stoplights or grocery stories. In 2011, a United Nations investigator visited Tulare County, called it “the poorest” (actually the second-poorest) “county in California,” and singled out the lack of safe drinking water in many communities.

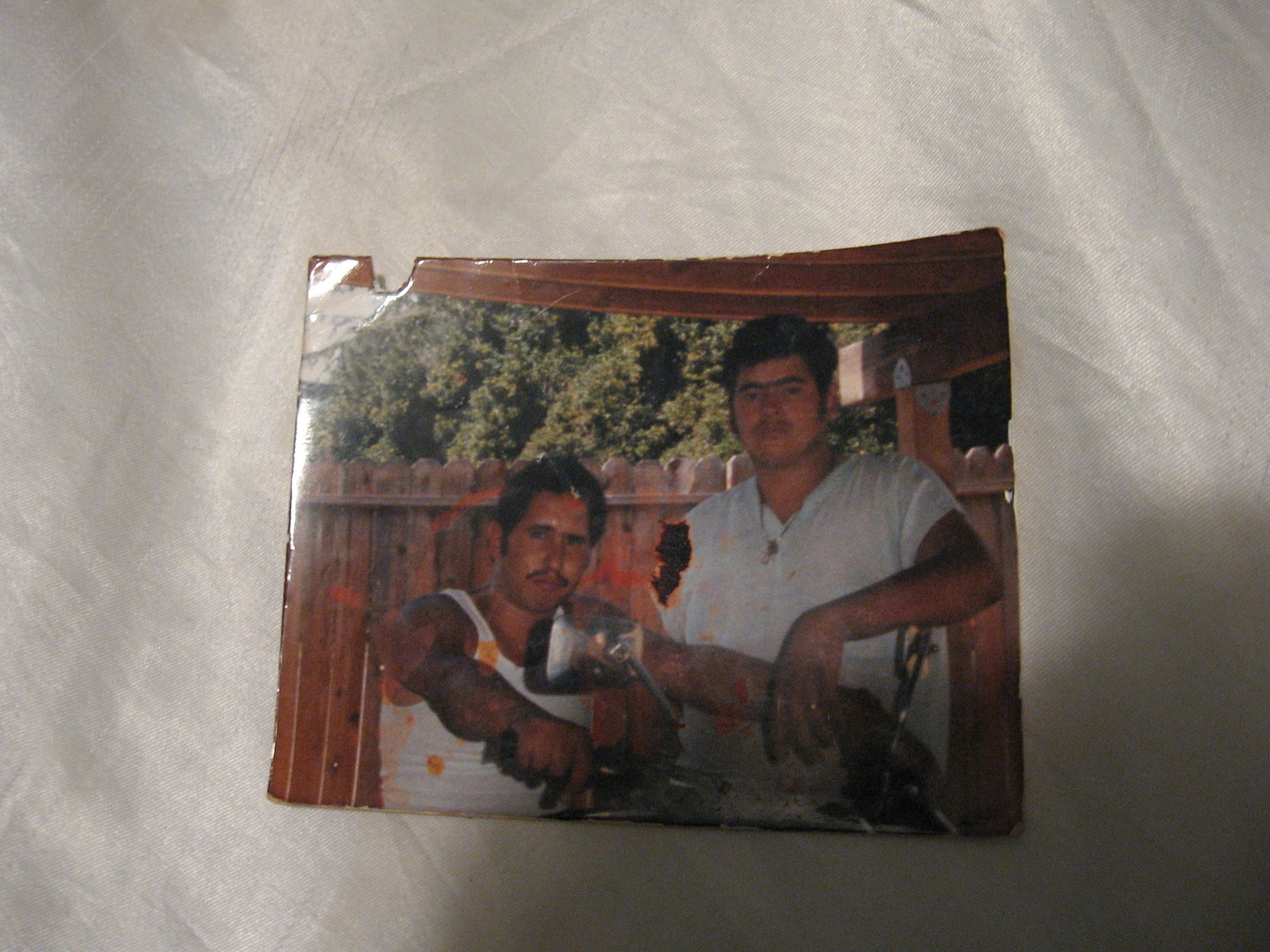

Martinez and his siblings spent part of their childhood in Mexico, near the town of Cosalá, in the remote, misty cool of the Sierra Madre, the mountain range that runs through the states of Sinaloa and Durango. In California he lived in the flat middle of the valley, on a ranch between the towns of Delano and Earlimart. His mother and stepfather managed housing for migrant farmworkers.

The family lived at the center of one of the greatest civil rights struggles of the 20th century: the epic battle to organize farmworkers. César Chávez, who led the struggle, passed through the area frequently. Martinez saw Chávez a few times but wasn't interested in the movement or in farmwork. “I don’t like to get up at 5 a.m. in the morning and go to the fields,” he said.

Martinez’s stepfather, Pedro Fernandez, helped line up work crews for grape growers, but was also a “businessman,” as his stepson put it; according to family members and newspaper accounts from the 1970s, his business was heroin. Before Martinez was even out of middle school, Fernandez tapped him to run drugs. As a bilingual, American-born teenager, he could move between worlds and below law enforcement’s radar. In the spring of 1976, his stepfather sent Martinez “on the Greyhound bus to Indio to pick a package for him on my graduation day.” That trip was so seminal that Martinez used it in the opening pages of an 84-page autobiography he wrote in the fall of 2014 while awaiting sentencing in California.

“When I pick the package, I told the guy what was in it, He told me it was Heroin. I was a kid. I din’t knew much about it.”

View this video on YouTube

After he returned to the US from Mexico and enrolled in elementary school, “People were making fun of me because I didn’t know how to speak English,” he said in an interview. He was obviously bright, but he dropped out of high school after only a couple of months. “I din’t realize how important education was!” he wrote.

He got a car, which allowed him to move heroin, and also to pick up girls. In 1977 he was 15. “That the year I stole my first wife. I say stole because she got in my car” — a 1969 yellow Ford Galaxie — “and I took off with her.” He added: “I think she like it, because we live together for almost 10 years or more.”

In September 1977, the Drug Enforcement Administration raided the ranch where Martinez lived, seizing $2.5 million worth of drugs and several firearms. His stepfather was sent to Lompoc federal prison, according to Martinez, who said he was washing his car when the agents stormed the place. “That was the first time they put handcuffs on me,” Martinez recalled in a letter. “They also made a mess of my bedroom.”

As for his stepfather and the others arrested that day, Martinez recalled: “A couple years later, they all came out. All happy like nothing had happened.”

“You feel something relax in your heart when you take revenge.”

But around the same time, tragedy struck: Martinez’s sister Cecilia was murdered. Her body was dumped near Bombay Beach at the edge of the Salton Sea, the vast, eerie lake that straddles Imperial and Riverside counties. She had followed a man down there, and now she was dead.

Martinez accompanied his distraught mother to the Riverside County sheriff to make a statement, but said he figured out on his own who her boyfriend and his associates were.

“That was the first three motherfuckers I killed,” he said.

Martinez said he dumped the bodies in unmarked graves. (Riverside County Sheriff’s officials in a statement said they have “an open homicide investigation” into the death of Cecilia Martinez and are “aware of the accusations” that Martinez took revenge on the killers, but have not substantiated them.)

It’s an origin story Martinez has told many detectives since his confession. He even got Los Corceles de Durango, a band whose songs often celebrate the exploits of the drug trade, to perform “El Corrido de Cecilia,” which tells the story of his sister’s death and the rough justice he administered.

“I was a nice man, until they killed my sister,” he said. “And since then, I said, ‘Fuck the rapers. And the child molesters.’ When my father was in the funeral, I told my dad, ‘I’m going to get those motherfuckers.’ He said, ‘Son, let God take care of them.’ I said, ‘Dad, God ain’t gonna do shit.’”

When he killed the people he believed were responsible for his sister’s death, “I feel so proud,” he recalled. “It was, I don’t know, you feel good. You feel something relax in your heart when you take revenge.”

No matter how many murders he cops to, he won’t be giving up the location of those three bodies. Those bones, he said, don’t deserve to be found.

“Easy money”

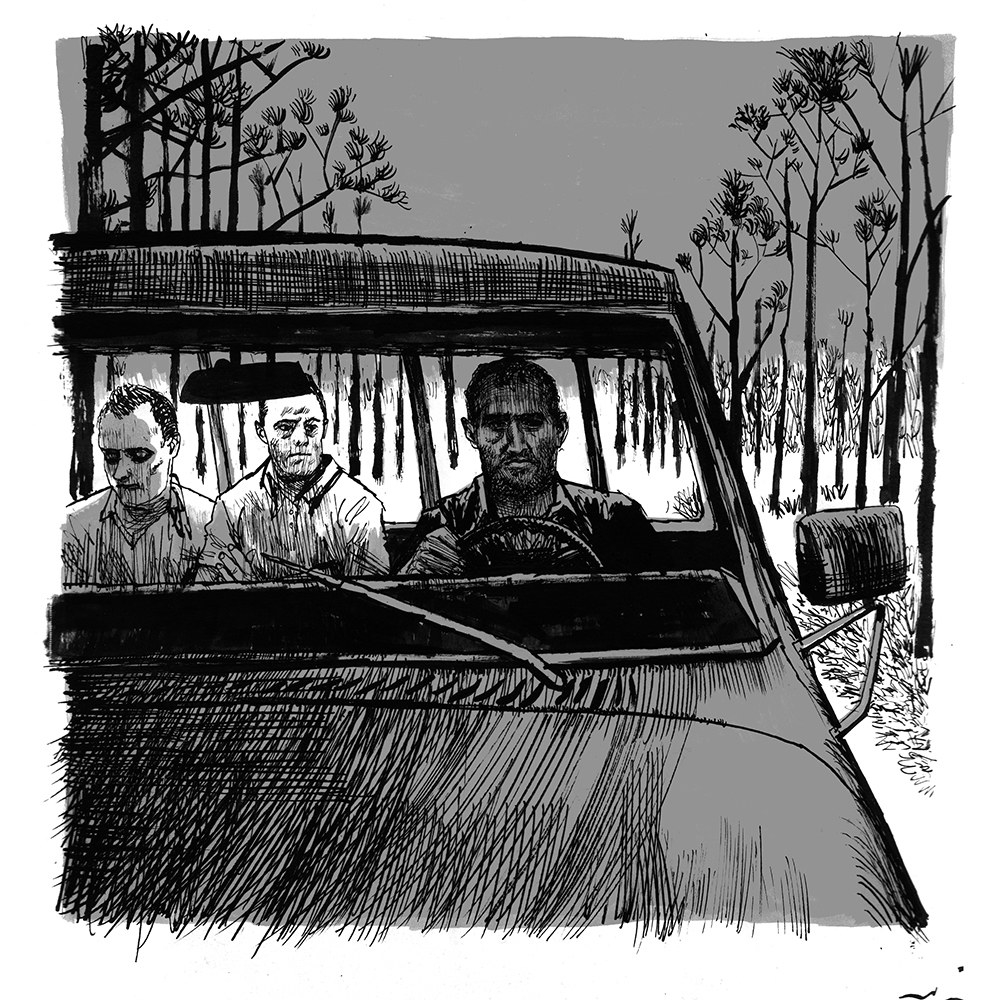

On the morning of Oct. 21, 1980, Martinez sat in the passenger seat of a friend’s car outside the home of David Bedolla. Bedolla emerged just before dawn, accompanied by his wife, headed for a grueling day picking grapes for subsistence wages. Martinez and his friend followed Bedolla’s little yellow car as it wound its way in the early morning gloaming down country roads, stopping once to pick up another worker.

Just a few hundred yards before the car reached the long rows of vines where the group would be working, Martinez fired a .22-caliber gun. Two bullets whipped past Bedolla’s wife and into the windshield. Two more hit Bedolla in the head. The car careened off the road and into a vineyard. Bedolla was killed.

Martinez had agreed to the job just hours before, while he was hanging out with a friend and getting high. Suddenly the conversation had turned serious. His friend had said his sister had been raped.

“500 Dollars were handy. Point & Shoot easy money.”

The friend — who, like all accomplices, Martinez refused to name — said his sister was still in Mexico but that the man who raped her was now living in California, in the farm town of Lindsay, with his wife and young son.

Martinez — who was just 18, with his own young son as well as a baby daughter who “made me so happy,” and a young wife — didn’t hesitate.

“I told him, I could help him for five Hundred Dollars,” he recalled. In a letter he added, “I felt anger when I heard the word Abuse. And 500 Dollars were handy. Point & Shoot easy money.”

When, 23 years later, he confessed to the murder, Martinez was matter-of-fact. “He raped a 16-year-old girl,” he said.

Bedolla’s death devastated his wife and clouded the future of their young son, creating a sorrow and emptiness that has yet to heal. “Since that date, we haven’t been happy,” she testified in court in 2015. “I’ve always — I’ve always had that in my mind.”

It had a more positive impact on Martinez.

“You worth the same dead or alive”

In June 1979, in a small town deep in the Sierra Madres, about 50 people gathered for a party, held at the home of a man who, like many others in his community, moved back and forth between Mexico and the agricultural communities of central California.

La Cofradía was far from cities, from paved roads. It was a town where people got around on horseback and fended for themselves, and where the drug trade was becoming more central to the economy.

At some point in the night a dispute arose over who was dancing with whom. Pistols came out. Four people were killed. Families vowed revenge.

In September 1982, Martinez was at home in Earlimart when he got a visit from a friend who said that one of those killed was a distant relative of Martinez’s. And he told him that two of those responsible were now in California.

One of the men, Silvestre Ayon, was living in Santa Barbara County — away, so he thought, from people who might recognize him.

On Oct. 1, according to Martinez’s own account, he and three other men set out from Kern County in the Central Valley and drove over the coastal range to Santa Ynez, an agricultural region that would later become famous for its pinot noir.

One of the men Martinez refers to only as “Mr. X.”

Mr. X would soon become a very important figure in Martinez’s life.

Just a few miles down the road from Ronald Reagan’s ranch, Martinez said he found Ayon driving a tractor and opened fire. Police reports say there were at least two shooters.

“Mr. X give me twenty five hundred Dollars,” Martinez wrote in his autobiography. “I really din’t want the money, I wanted to be like the same level he was. I wanted to show him what im capable of doing.”

Mr. X gave Martinez a pager, and he was in business.

"You have two hours to come up with the money."

Two weeks later the beeper went off. Mr. X was “having a little problem” with a man who owed him $95,000. By midnight, Martinez was in his car, speeding north on Highway 99 through orange orchards past the lights of Fresno that glow yellow through the valley haze.

As morning rose, Martinez found the debtor and brought him to an empty garage. “For me, you worth the same dead or alive,” he said he told him. “I’m still getting paid. You have two hours to come up with the money.”

Martinez drove the cash straight to Mr. X, he said, who gave him $30,000 for his troubles.

This kind of collection, according to both Martinez and police, was the bulk of his business, along with smuggling. In both endeavors, his steady nerves were his best asset. He recalled a time he was pulled over en route to Chicago. The officer said he was going to bring dogs to search his car. Martinez said he smiled and offered to help. Seeing Martinez so at ease, the officer decided to skip the search. If the dogs had come, Martinez said, they would have found 10 kilos of cocaine.

His work brought in a vast amount of cash. But Martinez’s daughter said he “didn’t care about money.” In fact, she said, he tended to give it away as soon as he got it, helping neighbors pay rent, buying things for his family, for his children, for anyone who seemed in need.

If smuggling and collecting paid the bills, murder was what set him apart. “I was so damn good,” he said.

Martinez said he taught himself to be an assassin in part by watching movies. He’s a fan of the Rambo series. “The first thing is not to get nervous,” he said. “And don’t leave evidence. Be patient.”

If the killings weighed on Martinez, he gave little sign of it. During the Ayon shooting, bullets also hit a teenage bystander, a high school student who worked on a ranch each morning before classes. Martinez barely shrugged. “Wrong place to be,” he wrote.

Martinez sometimes combined acts of violence with small gestures of empathy. He shot a man, Domingo Perez, merely for repeatedly parking in Martinez’s mother’s driveway. But Martinez knew the man’s family would need the car, so after the killing, he secretly returned it to their home. After a few days, no one had found Perez’s body, and Martinez said he heard that Perez’s mother “was going crazy” from worry. “I said to myself: Damn, I have a mother too.” So she could get some peace of mind, Martinez retrieved the corpse from where he’d left it, and he moved it to a more visible spot in an orange orchard, where it was soon found.

PART 3: GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER IN CALIFORNIA

Three weeks after the early-morning murder of David Bedolla, the phone rang at the Tulare County Sheriff’s Office with a tip. Homicide detective Ralph Diaz, in his clear, careful handwriting, wrote down the caller’s name: “a subject identifying himself as Jose Martinez.”

The caller offered some remarkably specific guidance about the killing, which he said was revenge for a stabbing during a card game. The caller also said that Bedolla may not have been the intended target. Diaz made a plan to meet the caller for a personal interview. The file does not say whether the meeting took place.

Years later, Martinez confessed to the murder but denied making that call. Still, the name Jose Martinez weaves through this and other case files like a bright thread. His name turns up as a source in one murder. As a figure in the events leading up to another. On several occasions, police thought he could be the killer. Even then, they never charged him with murder.

In September 2009, Martinez killed a man named Joaquin Barragan in Earlimart. Within days, police had learned from the victim’s friends that a person known as El Mano Negra had been looking for him and threatening to kill him. They knew that El Mano Negra was Martinez’s nickname, and that he had an outstanding warrant for a parole violation and possibly another for auto theft. They found a woman who said Martinez had attempted to hire her to lure Barragan to an isolated place.

They arrested Martinez on the parole violation, but, he said, he managed to swallow the SIM card from one of his phones before officers could see his text messages. (Police reports indicate that one officer had the idea to replace it with the SIM card from a police phone, but found that didn’t solve the problem.) They tried to interrogate him but got nowhere. “I asked Martinez if he could explain why everyone in Earlimart believed he was the person who killed Joaquin,” the police report states. “Martinez stated he did not know, and told me everyone in Earlimart is lying.” The interview lasted less than an hour. Martinez did a few months in jail for the parole violation. The murder remained unsolved.

“This city’s got no law”

Walk the sunbaked streets of Richgrove, the farming hamlet where Martinez lived with his family for many years, and it’s not hard to find people who say they knew him.

Some recall him as a dedicated family man who helped his mother take care of her peach-colored house on a windswept cul-de-sac. Some say he was a friendly figure, offering a neighbor a cold soda at the end of a hot day. And some will confide they heard whispers that he was a killer, that he went by the name El Mano Negra.

But it’s hard to find anyone who was surprised that police here didn’t get him.

“This city’s got no law,” explained one man in Richgrove who, like others, did not give permission for his name to be published.

Indeed, in Tulare County, where Martinez committed six of the murders he’s pleaded guilty to, some residents have complained that they need more protection from police.

It’s hard to find anyone who was surprised that police here didn’t get him.

A 2017 report prepared by the county about Earlimart noted that “residents report that the Sheriff’s Department response time is unacceptable and that there is limited Sheriff patrol within the community.” The report added that people “are very concerned with the rise in shootings and drug related violence over the last couple of years.”

In Richgrove, people also complained of long response times, “inconsistent” patrols, and “crimes that go un-responded to.”

Marguerite Melo, a former prosecutor who now works as a civil rights lawyer in Tulare County, suggested that these factors might have contributed to law enforcement’s failure to catch Martinez for so long. “In this county, there is no question that Latinos are treated very differently from white people,” said Melo. “None of those victims mattered to them as much.”

She speculated that “if Mr. Martinez had been killing people with a strong voice in the community, he would have been caught much earlier, because resources would have been dedicated to solving these crimes.”

Scott Logue, until recently Tulare County’s assistant sheriff, strongly rejected that notion.

“We didn't care if you were any kind of nationality, gender, political beliefs, anything like that,” he said. “Believe me, over the course of years, a lot of detectives were champing at the bit, wanting to prove Jose Manuel was responsible. A lot of blood, sweat, and tears went into the cases.”

At the same time, the prevalence of the drug trade here, and its attendant violence, sometimes overwhelms police. “We’ve had more than our fair share of cartel crimes,” said Brewer, the Kern County homicide detective, ticking off murders, attempted murders, and then the murder of witnesses who might have testified in the trials of the original crimes. According to the most recent state statistics, Kern County had the second-highest homicide rate among mid-sized or large counties, and Tulare County came in at number seven out of 58 counties.

Though little noticed by the outside world, these small, sleepy towns play a key distribution role in the movement of drugs into the United States, and the transit of guns and money that accompany the trade. In many cases, law enforcement officials said, drugs coming from Mexico bypass Los Angeles or San Diego entirely and arrive in stash houses in the Central Valley before heading to points north and east. Guns, which are harder to buy in Mexico than in the US, flow in the opposite direction.

Not far away, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas that rise up east of Tulare County, officials are also waging a battle over marijuana being grown on public lands — often, officials said, by armed work crews that occasionally shoot one another, pollute national parks, or spark huge wildfires.

The lucrative trade has infiltrated law enforcement. In the last few years the nearby Kern County Sheriff’s Office and Bakersfield Police Department watched in dismay as four officers pleaded guilty to being involved in drug sales or tipping off a drug dealer to an investigation.

The area has also functioned as a kind of farm team for Mexico’s fearsome drug cartels, nurturing a surprising number of people who have gone on to play prominent roles in their lethal drug war.

One young man from Tulare County, José María Guízar Valencia, crossed the border to Mexico and became a high-ranking member of the vicious Los Zetas, a cartel notorious for its bloody tactics and its habit of dumping murder victims in acid or publicly displaying bodies hanging from bridges. (Guízar Valencia was arrested in Mexico City in February.)

And investigators, according to an indictment unsealed in 2014, heard suspects in another part of the Central Valley talking about “partying with El Mayo Zambada,” otherwise known as Ismael Zambada García, one of the most powerful leaders of the Sinaloa cartel.

As officers patrolled the flatlands of Tulare and Kern counties, some heard the gossip that El Mano Negra was a contract killer. But there was so much other crime. So much other violence. Witnesses, when there were any, had a way of turning frightened and forgetful. “There’s no corroborating witnesses. There’s no physical evidence,” said Logue, the retired head of violent crimes for Tulare County. Barring a confession, there was little they could do, and Martinez was “a good liar” and “a sociopath,” he said. “You can know someone did something, but until someone can prove it...” He paused. “We have to work within a framework set forth by the law. You can only do what you can do.”

Martinez, he said, just “got away with it.”

“Deception is indicated”

And yet, sometimes it was almost as if Martinez were daring the Tulare sheriffs to catch him.

In March 2010, after he was released from prison on his parole violation, one of the first places he went was the violent crimes division of the Tulare County Sheriff’s Office.

Martinez said he wanted his Chevy Suburban back. Sheriff’s officials had seized it when they questioned him about Barragan’s murder. He offered to talk to them again about what he knew.

This time, Martinez went so far as to suggest to police that he was a collector for a drug cartel, which he said was based in Guadalajara. He also told police, according to their report, “Barragan was not murdered because he owed money, but because Barragan was a rat.”

Detective Cesar Fernandez decided to seize the moment. He asked Martinez if he would be willing to submit to a lie detector test on the question of who killed Barragan. Lie detector results are generally not admissible in court in California, but police often use them while conducting investigations. Martinez agreed to the test.

He was asked several questions about the murder, including whether he knew who did it.

The examiner found that “deception was indicated” when Martinez said he did not know who murdered Barragan.

The examiner asked to do a second test, which would be focused more on whether Martinez had carried out the killing.

“Did you murder Joaquin?”

Martinez answered no.

The results: “Deception was indicated.”

A second investigator did his own analysis of the results. He agreed: Martinez was lying when he said he didn’t commit the murder.

And yet, he was never charged.

Asked why they had not taken more action, a spokesperson for the department said officials “don’t move forward until the case is thoroughly investigated,” explaining that “once an arrest is made the case becomes time sensitive as the suspect has a right to an arraignment within 48 hours.”

“We ethically can’t charge anyone in California that we don’t feel we can prove guilty beyond a reasonable doubt,” said Assistant District Attorney David Alavezos, the prosecutor on the cases Martinez pleaded to. And he disputed the idea that law enforcement doesn’t care about these communities, noting that the county recently doubled the number of prosecutors in the area.

One of Barragan’s relatives gave the sheriff’s office credit for working the case hard. But still, he said, “They let him go, and he still killed more people.”

“Everybody knew,” he added. “Everybody is scared.”

PART 4: CATCHING A KILLER

The Florida job had gone off without a hitch — or so Martinez thought.

Javier Huerta, a masonry contractor with an apparent side business in cocaine, had been accused of stealing 10 kilos from another drug distributor.

Martinez, hired to collect the debt, flew into town in November 2006 and discovered his target was 20 years old. “‘Damn,’ I said, ‘this punk stole 10 kilos?’”

Martinez watched Huerta for a few days, passing up one opportunity to grab him because the man’s child was present. As he recalled telling Huerta: “Your little girl has nothing to do with the stupid things you do in your life.”

So he posed as a homeowner in need of masonry work. When Huerta showed up to bid on the job, Martinez kidnapped him and forced him to hand over approximately $200,000 in cash, $150,000 of which had been buried in his backyard.

Then Martinez shot him four times. He put another four bullets into one of his coworkers. Their bodies, wrists bound with zip ties, were left to rot in a Nissan truck parked on a swampy stretch of road at the edge of the Ocala National Forest.

Police figured out fairly quickly that they were dealing with a drug hit. They heard about the stolen cocaine and the money. But they got nowhere on who had ordered the hit and who had carried it out.

Martinez headed to his daughter’s house in Alabama. By chance, it was his granddaughter’s birthday. “I told her, get in the car,” he recalled, and they drove to the nearest Toys ‘R’ Us, where he said she could get everything she could put her hands on during their visit.

“You don’t want to know how much I spent on the Toys ‘R’ Us store,” Martinez recalled proudly.

Back in Florida, detectives inspecting Huerta’s truck found a Mountain Dew can in the center console. They emptied it and found a cigarette butt, which they bagged and tagged into evidence and sent off to the crime lab for testing.

It should have hit. Thanks to his arrests on drug charges, Martinez’s fingerprints should have been on file, along with his DNA. But for some reason, the results of the DNA swab never came back to the sheriff’s office. And, overwhelmed with mountains of evidence that all seemed to be leading them nowhere, no one seems to have noticed. For six years.

At 5 p.m. on Oct. 9, 2012, detectives in the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Ocala, Florida, earning overtime to reexamine cold cases, grabbed a thick case file labeled “Huerta,” sat down, and began to read.

They soon came across something startling: Some of the evidence, including the cigarette butt, had not been fully analyzed.

So they asked the crime lab at the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to run the search.

In the intervening years, Martinez had killed at least four — and as many as six — more people. And he wasn’t done yet.

The final murder

Unaware of what was happening in Florida, Martinez arrived in Alabama in the winter of 2013 for an extended visit with his daughter and granddaughters.

He’d pick up his granddaughters from school and play with them for hours. He let them dress him up like a Disney princess and subject him to a game of “spa day,” which ended when he gobbled up the avocado facial as the girls howled with laughter. When one was sick, he kept vigil at her bedside all night.

And he threw himself into helping his daughter, who was divorced and working on building her own roofing business. She’d find him up on ladders, trying to hammer at roof tiles. She chased him down, explaining that her insurance didn’t cover him.

Eventually he found an opportunity to contribute. Jose Ruiz, a friend of her then-boyfriend’s, had a debt to collect for his business. Martinez figured he could lend his expertise, and in the process get Ruiz to tell him a little bit more about the man his daughter was dating.

Instead, Ruiz, according to police and Martinez, made a fateful mistake. Not knowing who Martinez was, or, more crucially, who his daughter was, Ruiz described his friend’s girlfriend as a bitch and a slut and a terrible mother.

Martinez was enraged. Ruiz, he decided, would have to die. But he said nothing at the time. He knew that he and Ruiz had been seen together. Ruiz’s DNA was all over the car Martinez was driving. Revenge would have to wait.

So he went home to California to be with his mother. As the winter sky hung low over the fields, parched after years of drought, his anger over Ruiz’s comments festered.

Evidence Item 28

On Feb. 27, 2013, Detective T.J. Watts, of Marion County, Florida — six years late — finally got the crime lab report on the forgotten cigarette butt.

It revealed that Evidence Item 28, a cigarette butt from a Mountain Dew can, had hit a match against a man once held in prison in California: Jose Manuel Martinez, of Richgrove, California.

The victim had frequently driven workers and clients to job sites. The cigarette butt could belong to any one of those people. There was no reason to assume that one DNA match would solve the case — much less that the suspect was a serial murderer and that acting quickly could save other lives.

“Drive, and keep your mouth shut.”

Martinez returned to Alabama from California, and on March 4, 2013, five days after detectives over in Florida received the lab report on Evidence Item 28, he found a pretext to go for a ride with Ruiz and his daughter’s boyfriend, Jaime Romero.

At Martinez’s direction, they drove south and west, through ever-smaller towns that petered out into fields of hay and then eventually dissolved into the Bankhead National Forest of dense, old-growth trees cloaking mossy green canyons and sparkling waterfalls. When they stopped next to a hayfield to stretch their legs, Martinez pulled out a gun.

The woman you bad-mouthed “is my daughter, you stupid son of a bitch,” Martinez said. He fired his gun, shooting Ruiz twice in the head.

Martinez watched Ruiz’s body crumple to the ground. He got back in the car and glared at the startled Romero.

“Drive,” he said, “and keep your mouth shut.”

In the remote field where Martinez shot him, Jose Ruiz’s body might not have been discovered for a long time. But as it happened, nearby hunters heard the shots and came upon it in less than an hour. Tim McWhorter, the Lawrence County Sheriff’s chief investigator, arrived at the scene and looked down at the lifeless body.

Police let him go

Martinez was back in California, at the Earlimart home where his sons lived, when local police showed up at his door on April 16. With the murder he had committed in Alabama fresh in his mind, Martinez took one look at them and bolted out the back.

Tulare County Sheriff’s Deputy Christal Derington gave chase. But Martinez had run for nothing. Derington didn’t know anything about the Alabama killing. She was part of a task force investigating a series of violent, drug-related robberies, one of which involved an allegation of attempted sexual assault.

Martinez was not a suspect, but he was a felon in possession of ammunition. As cops were cuffing him, a colleague whispered to Derington that he was El Mano Negra, the man who was rumored to be a hired assassin, the man who had been suspected of involvement in at least four local murders.

This man? With his pleasant air and wry humor?

During the drive to the station, Derington told Martinez about the string of stash-house robberies. Hearing the part about a young woman threatened with gang rape, Martinez appeared almost on the verge of tears. He told her he couldn’t bear the idea of men hurting women.

Derington said she was not naive. She knew the man in the back of her car was a criminal, likely a violent, manipulative one. She knew he was working some kind of angle, although she didn’t know what it was. But he was also fascinating to talk to.

Authorities could have locked Martinez up for the ammunition they found, but they let him walk free with a promise that he would help them.

“Clue number one”

On Thursday, April 25, 2013, Detective Watts, on the cold-case beat in Florida, reached the Kern County Sheriff’s Office. Martinez was not a prime suspect in the murder Watts was investigating. He was just curious about why a cigarette butt with the DNA of a California man had been all the way in Florida.

The phone call changed things.

Brewer, a longtime homicide detective in the department, told Watts about Martinez’s history, including, according to Watts’s report, that he had “been involved in approximately five homicide cases in their area.” Some involved zip ties, just as Watts’s Florida murders had.

“That gave me clue number one, that I may have my man,” Watts said. “It was far-fetched, but I was starting to think, This guy could be one of those cartel guys.”

But it also left Watts with questions. What had Martinez been doing in Florida? And why on earth were Tulare officials enlisting Martinez’s help to solve lesser crimes instead of building a murder case against him?

“I was more than shocked by it,” Watts said. "I said, ‘Man, this guy ain't no informant — he's a killer.’"

Figuring Tulare and Kern officials would keep him in their sights, Watts flagged Martinez as a person of interest and went back to trying to find other leads.

In May, Martinez got antsy. He drove to Bakersfield, dumped his car, picked up another one that couldn’t be traced back to him, and drove 300 miles to the border.

He was in Mexico, a country that rarely extradites people accused of murder to the United States, particularly if there is a chance they will face life in prison or death. Martinez had escaped.

“I was trembling, waiting to talk to that guy”

Standing in the dirt, staring at Ruiz’s corpse in the Alabama hayfield, Detective McWhorter noticed the dead man’s face and said: “I know that guy.”

One of his colleagues shook his head. McWhorter had to be mistaken, his colleague said, because all Mexicans look the same.

But McWhorter did know Ruiz. He had hired him to put a new roof on his home. McWhorter, who had spent his whole life in these parts, knew a lot of people in the area. From Moulton, the county seat, he had spent part of his childhood in nearby Hartselle and then, after high school, moved straight back to Moulton, where he followed his father into the sheriff’s office. He started at age 19 as a jailer, then worked as a school resource officer and patrol officer, and finally as an investigator. Along the way, he had four boys.

"I said, ‘Man, this guy ain't no informant — he's a killer.’"

He didn’t make much money — even with nearly two decades on the force his salary was only around $50,000 a year. To generate extra income, he has a side business building cabinets. Sometimes, his day job, with its constant exposure to the worst instincts of humanity, made him so cynical that he would sit in church, look at his fellow parishioners, and wonder what evil things they had done. Still, whenever other departments tried to lure him for better-paying jobs in bigger places, he turned them down. He was proud of his department: During the seven years he was chief investigator of the Lawrence County Sheriff’s Office, he said, there had never been a killing that he and his team couldn’t solve. What’s more: “This is home,” he said. “You know the people here.”

McWhorter recalled Ruiz as a nice guy. Who would want to kill him?

Clues fell into place very quickly. But they did not point to Martinez.

Next to Ruiz’s body, officers found a Walmart receipt. One of the store’s many surveillance cameras led them to images of Romero, Ruiz’s friend, the one who was dating Martinez’s daughter.

They found Ruiz’s truck in a parking lot in Decatur, and they found more surveillance camera footage showing a truck pulling up next to Ruiz’s not long before the murder. They ran the license plate. It came back registered to Romero.

“Jaime’s the guy that done this,” McWhorter recalled thinking.

On the afternoon of March 11, 2013, McWhorter and his team traced Romero to Martinez’s daughter’s house and banged on the door.

Martinez’s daughter, who has her dad’s warm brown eyes and quick wit — and who asked that her name not be used in this article — told BuzzFeed News she had no idea her father was a contract killer, but she did know he was a criminal. She knew he had smuggled people across the US–Mexico border. He had even tried to get her to join the United States Border Patrol, the better to help his business.

In her own life, she was determined to walk a very different path. She had always followed the rules, even when it seemed like those rules were set up to keep people like her extended family of farmworkers down. After high school, she got as far away from home as possible. She enlisted in the Army and was stationed in Germany before settling in Alabama. She and her husband live on a country lane that affords vistas of giant white clouds and rolling fields, and are raising a family that now includes six children whom they shuttle to school and soccer games and gather around the kitchen table each night for dinner and homework.

And yet, she adored her dad. When the Army gave her a choice of jobs, she picked mechanic, because her dad was great with cars and she thought it would make him proud. When he came to visit, she dropped everything to make his time with her special.

His long visit in 2013, when he had so doted on his grandchildren, had exceeded all her expectations. She had begun to entertain hopes for a future in which her dad gave up his criminal activities and lived with her for at least part of every year, a steady, loving presence in her children’s lives in the way he had not always been in her own.

But now, a phalanx of cops was standing on her doorstep. And they were hauling off her boyfriend, Romero, who was wanted for murder.

Her father tried to help. Full of affable humility, Martinez went down to the police station, presented himself as just a loving father visiting his daughter from California, and swore that Romero had been with him at the time of the murder.

McWhorter recalled being taken in, as so many cops had been before, by Martinez’s “aw-shucks kind of guy” persona.

But as they were wrapping up their conversation, McWhorter, perhaps fishing for a regional compliment, asked Martinez whether he found people in Alabama to be more courteous than folks in California.

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

Martinez answered that for the most part he did, but he had recently had “a bad encounter.” Dropping one of his granddaughters at school, he had been so focused on waving goodbye that he had bumped into another parent, who refused his apology and told him to “watch where the hell you’re going.”

McWhorter vividly remembered what Martinez said next: “I looked at her and said, ‘Bitch, get out of my way.’”

“You could see the anger,” McWhorter marveled. “It was like you flipped a switch.”

The alibi Martinez offered for Romero didn’t work. A month after his arrest, Romero, with murder charges still hanging over him, requested to speak to McWhorter. In person.

Romero didn’t speak English, and the Lawrence County Sheriff’s Office didn’t have anyone who spoke Spanish. So McWhorter called in the high school football coach and Spanish teacher.

“I want to tell you the whole story,” Romero said. He wasn’t the killer. It was the man who had come to vouch for him. His girlfriend’s father. Jose Martinez.

Remembering his brief glimpse of Martinez’s fury, McWhorter believed he could be the killer. “But I was thinking, OK, maybe Romero put him up to it.” McWhorter called Tulare officials and said he learned that Martinez had a criminal record for drugs and had been a person of interest in a shooting. Soon after that call, McWhorter learned Martinez had left the state and was probably in Mexico. Which was only the most obvious of the many obstacles McWhorter faced.

“We knew as far as a conviction, we were lacking a whole lot,” he said.

Still, McWhorter decided to try. “I said, ‘This is all we’ve got, this is where we’re at, and I think we owe it to the victim’s family to try. If it fails, we’re going to fail trying.’”

"If you let it go like some people might,” added McWhorter’s then-boss, Sheriff Mitchell, “you let a murderer walk off totally free, just because you didn’t want to get embarrassed a little bit in court by having a weak witness."

McWhorter got his warrant. And very shortly thereafter, he got his man.

On Friday, May 17, Martinez walked back into the United States on the pedestrian-bridge border crossing from San Luis Río Colorado in the Mexican state of Sonora. A routine records check revealed the newly filed warrant.

“They told me I had a warrant for murder,” Martinez said. “I said, ‘Warrant from where?’”

Martinez was packed off to jail in Yuma, Arizona, to await transfer to Alabama.

A killer confesses

McWhorter got the call and together with another investigator flew down to Arizona to collect Martinez. On the plane home, they deliberately avoided asking him anything about the crime, instead chatting with him about life, the military, and the surprising deliciousness of the pizza they shared during a refueling stop in Lubbock, Texas. McWhorter was surprised by how unconcerned Martinez seemed to be about the fact that he had been arrested on murder charges.

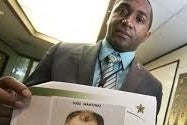

When McWhorter and Martinez arrived at the Lawrence County Sheriff’s Office, Detective Watts from Florida, who had been alerted to Martinez’s arrest, was already there, eager to talk to him.

McWhorter told Watts he had to wait.

“No hard feelings, buddy, but you got DNA. We need a confession,” he said he told him, before practically shutting the door of the interview room in Watts’s face.

“I was trembling,” Watts said, “waiting to talk to that guy.”

“No hard feelings, buddy, but you got DNA. We need a confession.”

Neither detective expected Martinez to confess. McWhorter said he thought Martinez would tell him to “pound sand” and then sit in jail for a while and maybe slip up on a recorded line on the prison phone system. Best-case scenario, McWhorter said, was that Martinez might admit to being at the murder scene, but try to pin it all on Romero.

Instead, Martinez confessed almost immediately to killing Ruiz.

After McWhorter let Watts have a go, Martinez made a confession in the Florida murder, too, giving detailed descriptions of the crime scene and the number of bullets used and telling him: “If I didn’t do the job, someone would have.”

He told Watts that he was confessing because he had decided the time had come to pay for what he had done.

He said there were some things in California that he wanted to get off his chest as well. He asked McWhorter to call Derington, the sheriff’s deputy from Tulare County.

When she walked into the interview room, Martinez smiled warmly and inquired politely about her journey. Then he got right to the point: He was a contract killer.

The Tulare County victims came so fast, Derington could hardly keep track. Sitting across from Martinez, she frantically texted her bosses back in Visalia with names, dates, and descriptions of roads, orchards, and ditches where Martinez said he had left bodies.

Brewer, the Kern County homicide detective, flew out next. The confessions he took home from that meeting allowed him to close two murder cases. In the process, he fell in love with northwestern Alabama and said he’d considered retiring there.

Some police were skeptical. Maybe Martinez knew about such crimes, but could he really have committed them all? But in case after case — even some that were 30 years in the past — he mentioned details that only the killer could know. Police were stunned by the quality of his memory.

“The place, the kind of car he was driving, the caliber of bullets. Even the shell casings. ‘You found this many shell casings at the scene,’” McWhorter recalled him saying.

Police would step out of the room and shake their heads in wonder, McWhorter said, telling each other: “Man, that is spot-on.”

Martinez didn’t know much about the lives of the people he had killed, how many children they had, what their jobs were. But he was sure — though he couldn’t offer proof — that they had hurt women or children, so he had no doubt they deserved what they got.

“He told me he had never killed a good person,” recalled McWhorter.

About the people he was working for or with, however, he wouldn’t say a word.

“You had to do everything with Jose on his terms,” McWhorter said. He told other investigators, “Don’t come in and try to bulldog him. Don’t try to act like a cop.” The goal was to keep Martinez talking.

Martinez recalled that FBI agents came from Washington, DC, to interview him — but mostly seemed interested in whether he knew where to find Joaquín Guzmán Loera, more commonly known as El Chapo, the head of the Sinaloa drug cartel. Guzmán was captured in 2016 after a gun battle ended one of the most far-reaching manhunts in Mexican history.

Martinez said he told the FBI to “have a nice trip” home, adding that murder was not a federal crime (though the department does have jurisdiction in cases like Martinez’s) and he wasn’t going to tell them anything.

Another topic that Martinez did not like, some officers said, was guilt.

Logue, from Tulare County, told Martinez toward the end of one interview session that he wanted to know “why you did what you did, how you feel about it, the psychology of it.”

“Do you have remorse for what you did?” he asked.

Martinez leaned forward. “What does that mean?”

“Are you sorry?” Logue asked.

Martinez nodded like a student who knew the right answer. “Yes. Yesterday the priest came and talked to me.”

“How about before the priest came — were you sorry?”

“No,” he shot back, staring straight at Logue’s face. “I hated those guys. For example, when they molested a little girl, the little girl going to have that on her mind, the rest of her life, every time she sees a man.”

“Why? Why? Why?”

From his jail cell in Florida, Martinez writes his granddaughters and other members of his family long, loving letters full of advice that could be issued from any church pulpit or parenting book, stressing the importance of being kind and considerate.

Meanwhile, Martinez’s family, the families of his victims, and the police officers who finally brought him to account for at least some of his crimes struggle to make sense of his actions.

His daughter, who left California with her mother and brothers when her parents split up, grew up thinking her father was a mechanic. She would see him “greasy from fixing cars” with a giant smile and brimming with love.

After the murder of Ruiz, she said, “it set in that he could kill someone. It felt unreal.” She and her children visited him in jail in Alabama and now video chat with him in his Florida jail, and what they see “is their funny, loving, storytelling, caring grandfather,” she said, “not a serial killer. And that is what I see also. A loving father.”

“He confessed because he was tired of it. Tired of hiding and tired of always watching behind his shoulder.”

She said she can’t bring herself to dig into the publicly available information about his killings, but she believes they were part of a twisted pursuit of justice, a vigilante action against bad people who were hurting others and getting away with it.

As for his confession, she is sure that it was a gesture toward redemption.

“He confessed because he was tired of it,” she said. “Tired of hiding and tired of always watching behind his shoulder. Finally being able to breathe, and not necessarily be free, but be free of all that in his head.”

She is convinced that her father’s extended visit with her in Alabama, the one that culminated in the murder of Ruiz, had a profound effect on him. “It was the first time he really felt surrounded by the love of a family, and it changed him.”

The family members of Martinez’s victims, meanwhile, continue to reel. Years and even decades later, they remain shadowed by loss and fear.

“We are not the same people we were before,” the mother of one Martinez victim told a judge in 2015. “My husband became a very bitter person. We stopped celebrating our birthdays, Christmas, New Year’s, for a while. Nothing was the same anymore. Then we would have a normal gathering. We would start out okay, but end up crying for him, because we miss him dearly.”

Another young woman, who was a child when Martinez murdered her father but who did not want her name used because she is still frightened of Martinez and his associates, said she used to write her father a letter every night for years after he died, desperate to hold onto him and keep his memory alive.

The family struggled not only with suffocating grief, but also with financial hardship. They lost their house and had trouble keeping food on the table.

Finances are better now, but the empty space remains. Recently, she said, her young daughter asked her if she had a grandpa like her friends, and she felt the grief rear up.

Terror continues to consume her. She is obsessed with stories of serial murderers and afraid to stay at home by herself. At any mention of the crime, she falls into a spiral of fear and despair.

“My dad is dead,” she said. “Why? Why? Why?”

PART 5: BUZZFEED NEWS REVIVES COLD CASES

In the five years since Martinez began confessing, authorities have used the information to close a number of old murder cases. He’s pleaded guilty to nine murders in California and one in Alabama. The two in Florida he is facing trial on bring the total to 12.

The various police agencies celebrated these accomplishments with press releases touting their diligent work and the closure brought to families.

Those 12 killings are not, however, even half of the total number Martinez has claimed to have carried out.

Martinez told at least three different agencies that he had murdered more than 30 people. At one point, he showed officers in Alabama a piece of paper — which McWhorter kept — on which he had listed, in his careful handwriting, the names of 12 states, accounting for a total of about three dozen victims. He told BuzzFeed News the figure was 36.

That means, police acknowledge, there are many families still waiting and wondering what happened to their sons or fathers. So BuzzFeed News attempted to do what many police officers around the country didn’t when news of his confessions broke: reexamine cold cases.

Some of the places where Martinez said he killed people are big cities, such as Seattle and St. Louis, where there are so many unsolved murders from the 1980s and ’90s that it would be difficult to try to identify cases that fit Martinez’s MO.

But Martinez also said he killed men in smaller, less populated jurisdictions, such as Salem, Oregon, and Twin Falls, Idaho, in 1985; Walla Walla, Washington, in 1986; and Waterloo, Iowa, in 1988. Though he gave no details beyond place and approximate year, BuzzFeed News went searching for open, unsolved cold cases from that period, looking for any that fit Martinez’s pattern — male bodies of Latino origin, left in isolated fields, stabbed or shot.

On a rainy Saturday afternoon in October 1986, according to a story that year in the Salem Statesman Journal, 15-year-old Jeromy Landauer, out for a day of fishing near Horseshoe Lake, instead “found a corpse.”

The paper reported that the “odor of decomposing flesh wafted from among the brush and trees.” Jeromy ran to his friend, looking “white as a ghost,” then called police.

The medical examiner determined that the body was male, likely of Latino descent and in his thirties. He had been tied up, and was therefore probably a victim of murder, and had likely been killed elsewhere and then “just dumped.” Police also noted that the victim had several distinctive tattoos, including of a scorpion. A sidebar story, which included an interview with a tattoo artist, speculated — without much explanation — that the tattoos had been inked either in prison or in Mexico.

The story also noted that Detective Ralph Nicholson, an 18-year veteran officer, was stumped. “Not many murderers have left him with such a cold trail,” the story said.

And that was that. Several more short stories over the years noted that the killer was still at large and police, apparently, still stumped.

Outside Twin Falls, Idaho, in the town of Buhl, a pair of teenage Boy Scouts in the spring of 1985 came upon what they initially thought was a cow skeleton. It turned out to be the skeleton of someone police later said had likely been stabbed to death. Authorities determined the victim was likely male and Mexican or Mexican American. After talking to local farmers, they concluded the body may have been dumped there in the summer of 1984.

“Do they have any reward on those cases? We can be partners on the reward, Crime Pays. You know what I mean.”

Police got a welter of confusing tips. Among them: that the crime involved farmworkers, that it involved the Mexican Mafia, that the motive was to avenge a rape, that the motive was to punish someone who had stolen cocaine, and that it had all stemmed from a fight at a labor camp. The case went cold.

Both the Oregon murder at Horseshoe Lake and the Idaho cold case matched details that Martinez described in one of his autobiographies. When asked about the murders last year, Martinez wrote: “Do either of those ring any bells? Yes. Do they have any reward on those cases? We can be partners on the reward, Crime Pays. You know what I mean.”

Later, in a telephone interview, Martinez said he is responsible for the Idaho killing. “For drug debt, something like that.” He didn’t remember the name, but said it might have been 1984 or 1985, maybe in the spring.

And the body at Oregon’s Horseshoe Lake? “Shot him,” Martinez said. “A couple of times” with a 9-millimeter. “My favorite gun.”

He also added that he had said as much to Oregon Detective Mike Myers from the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, who came to visit him in Florida in late February or early March — three decades after the killing at Horseshoe Lake, but only shortly after BuzzFeed News began asking the department about it. Myers, Martinez said, arrived with a sheaf of papers and a lot of questions.

Myers declined to comment. Nicholson, the original detective on the case, did not respond to phone messages. Jeromy Landauer, the 15-year-old who found the body, could not be reached. In an email, the sheriff’s office’s public information officer wrote: “I am sorry I am still unable to provide any information regarding this case.”

In a phone interview, Martinez added a chilling coda: The man he murdered in Oregon, he said, “was a mistake.” A “random guy.” It was the second time that had happened, he said.

There are plenty more potential leads.

Martinez said he left three bodies in Tulare County. He wouldn’t give their names or many details, but he drew a rough map.

Officials obtained an excavator and visited the site with a cadaver dog on loan from Los Angeles County. The dogs picked up a scent, not where Martinez had directed them, he said, but in a different spot. That’s where officials dug. They found nothing.

Martinez insists the bodies are still there, and, in one letter, promised to reveal their exact location soon. “Be ready to travel to Richgrove,” he wrote me. “Don’t forget a shovel and a camera crew.” He added, unbidden, that he would not be shelling out for funeral expenses.

“They were so close to me”

Martinez has another way of passing the time in prison: He pores over police reports of his killings, analyzing all the ways the cops slipped up.

The officers in Tulare are the ones he knows best. Over the years, they arrested him repeatedly for lesser crimes, questioned him about murders, searched his cars, seized his guns, and talked to his family members. But they never nailed him.

“I always said, and always will say, Tulare County sheriffs are so stupid,” he wrote in a letter.

The agency that did the best job, he said, was the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office. After he murdered Ayon in Santa Ynez in 1982, he said, “they were fucking — they were so close to me.”

Indeed, the case file on that murder stretches over a decade. Officers on that case included Bruce Correll, who later advised the best-selling mystery novelist Sue Grafton as she sent her character, private eye Kinsey Millhone, tromping across “Santa Teresa” to solve crimes. Officers visited multiple counties, including Fresno, Del Norte, and Martinez’s home turf of Tulare. They searched a home in Los Angeles County and found wads of cash; “receipts for Rolex wristwatches”; “many pairs of expensive men’s cowboy boots in exotic hides”; and ammunition for multiple guns, including more than 100 rounds for an AK-47. Within a month of the murder, Santa Barbara detectives had identified a possible connection between the killing in their county and another murder Martinez ultimately pleaded to in Tulare County. In July 1991, Santa Barbara detectives even went to the Martinez family home in Richgrove to interview a witness.

“Martinez was good, but he was also lucky,” said Correll, who retired in 2002 as a chief deputy of Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department and said he has since worked on the Golden State Killer case.

In the end, the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Office arrested a suspect and turned him over to Mexican authorities. But they didn’t get Martinez.

“Martinez was good, but he was also lucky.”

The irony was not lost on McWhorter. He remembered talking about it with Martinez: “You’ve been in all these big cities, and never been caught, and you come to Lawrence County, Alabama, and you get caught.”

McWhorter said Martinez laughed. Then he told the small-town cop not to get too full of himself. The only reason McWhorter caught him was that Martinez made a mistake: He left Romero alive.

Like almost all the detectives who worked the Martinez case, McWhorter said he had never met a criminal quite like him. “I’ll be honest with you,” McWhorter said. “When he got to talking about these other murders, all I needed was a tub of popcorn. We just sat there in silence.”

McWhorter said he thinks Martinez “was just very proud of what he had done. So he thought, ‘They’ve got me. This is my opportunity to get fame or glory.’”

McWhorter himself gleaned a bit of glory from the Martinez case. He was quoted in newspapers when Martinez confessed and he was invited to speak at a law enforcement conference. But more recently he was fired from the department, in a tangle of accusations and counteraccusations. McWhorter has requested an investigation to clear his name.

Martinez, the subject of so much of McWhorter’s attention, appears to have returned the favor, making a shrewd study of his examiner. From his jail cell, he’s managed to learn a great deal about the detective, including what his salary was, who his father was, and where he lived.

What did he make of the man who finally got him? Martinez’s answer was simple: “He’s an asshole.” And McWhorter hadn’t really caught him, he clarified. “He was trying to interrogate my little granddaughter, and I didn’t like that. That’s why I’m in jail. I came back.”

But up until the last moment, he wasn’t necessarily planning to confess.

“I was going to come back and shoot his ass.” ●

Note on sourcing: This story is based on dozens of interviews with law enforcement officials around the country, with residents of Tulare and Kern counties, an exchange of letters and jailhouse interviews with Jose Manuel Martinez, interviews with members of his family, as well as a review of thousands of pages of court records and police records and audio and video records from California, Florida, and Alabama.

Opening image credits: Illustration by Federico Yankelevich for BuzzFeed News; Marion County via FOIA (5).