The inmate in cell #208 hugged her friend good night and goodbye and willed herself into a couple hours of sleep. Before dawn, Arlena Lindley was up again, boarding a bus to a low-slung brick building with a sign that said "RELEASING." Inside, guards handed Arlena her birth certificate and Social Security card, along with a striped button-down and pinstriped men’s slacks several sizes too big. She walked up to the front gate.

Arlena’s father, Roy, and his twin sister, Joy, sat in a white Ford Edge. Roy had been in the hospital, and he'd nearly missed this day. Arlena had spent her final few prison phone calls imploring him not to do too much around his apartment. She could take care of all that when she got out, she said. It was no use. “I can’t but do it,” he told me.

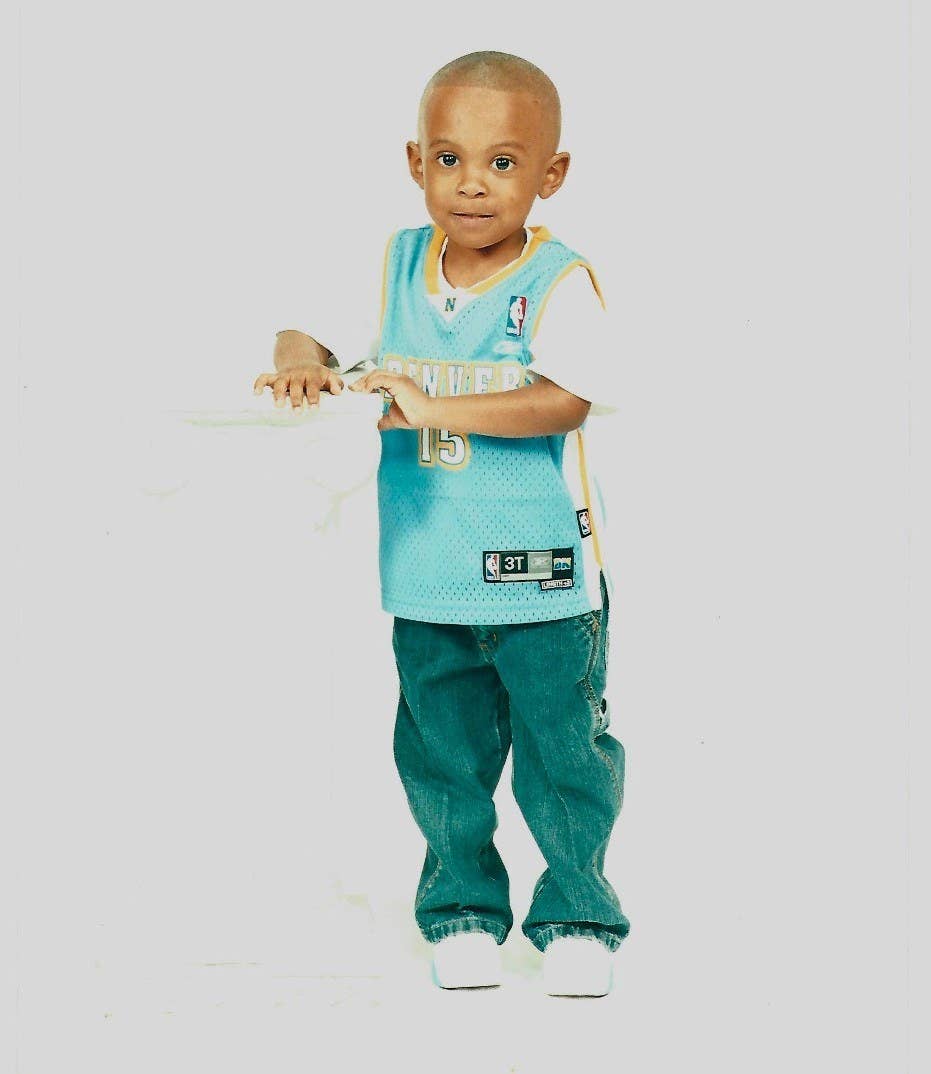

Arlena was already in jail when her toddler son, Titches, was buried, nine years and 11 months ago. So Roy brought home some of the plants from the chapel, including a sprawling ivy with a stuffed dove perched at the top. He decided he’d water and trim them so Arlena could see them when she got out, along with the box stuffed with Titches’ belongings and a CD of funeral pictures.

Arlena was convicted of failure to protect Titches from her boyfriend, who beat him to death when he was 3 years old. Arlena was sentenced to 45 years, a term that wasn’t due to expire until Roy was 98 years old. Yet he continued to water and trim, year after year, and hitch rides with Titches' grandmother, Cathy Lee, to visit Arlena in prison when he could. Then came sudden vindication: Arlena won her release in January of this year, 35 years and eight months early. The ivy was waiting for her at Roy’s apartment, right inside the front door, its branches crawling onto a nearby desk.

A guard waved the Ford Edge forward, the gate opened, and Arlena hopped in the back.

They spent much of the drive laughing, especially as Arlena absorbed her first shocks to the system. She chewed her first piece of gum in years. Roy, a 63-year-old retiree, showed his 30-year-old daughter how to take a selfie.

As the plains gave way and Dallas came into view, the car turned quiet. Joy looked back and saw Arlena thumbing through her Bible. Soon she’d be home, and it was still only morning. Arlena had many people to see and many more papers to sign — and something else she had waited years to do. She would buy a Spiderman toy and some flowers, and visit Titches at his grave for the very first time. She’d go by herself, so she and Titches could be alone.

Nearly all of Arlena’s adult life had been defined by someone else’s control over her. It started with her boyfriend, Alonzo Turner, whom she met when she was a 20-year-old single mother. A few months into their relationship, he started hitting her, and then he started hitting Titches. She tried to escape once and he threw her in the trunk of his car. She tried to escape a second time, after he whipped Titches with a belt and threw him against the wall. He snatched her son away from her and threw her out of their home. While she waited out of sight for Alonzo to calm down, a witness saw him kicking Titches in the stomach as he lay on the floor. Soon after Arlena returned to the apartment, Titches stopped breathing.

Then the state of Texas stepped in. Under the law, failing to protect a child is a crime. One of the police officers she had been working with, to build a case against Alonzo, arrested her. Unable to afford bail, she grieved for her son in county lockup, entirely alone and yet in front of an audience of incarcerated strangers. She’d try like hell to keep it to herself, and then she’d be eating sweet corn in the canteen or she would spot other inmates getting drawings and report cards from their kids and she’d just burst into tears.

After waiting 15 months in jail, Arlena pled guilty. Prosecutors asked for a 10-year prison term; her public defender asked for time served. At the end of the hearing, Arlena stood. Judge Jeanine Howard sentenced her to 45 years in prison. Arlena collapsed.

She passed time at the William P. Hobby Unit, an all-women’s prison in a tiny Texas town called Marlin, by working — first at meal times serving food to prison guards, and later on during the graveyard shift, cooking eggs and pancakes in the kitchen. She took parenting classes and latched on to the instructor’s self-help message. She kept to herself, studiously avoiding prison gossip.

She lost her court appeal, then the parole board denied her first bid for early release, citing reason 2D: The inmate either showed “a conscious disregard for the lives, safety, or property of others” or exhibited “brutality, violence, or conscious selection of victim’s vulnerability” and posed “a continuing threat to public safety.” At no time had Arlena ever been accused of hurting Titches herself.

In the spring of 2014, I sent Arlena a letter saying I was writing about cases like hers and asked her for an interview. On lined paper written in pencil, she replied that she’d be happy to share, “to help other people and give an honest outlook.” Five months later, BuzzFeed News published my investigation showing that Arlena and other mothers around the country have received lengthy prison sentences for failing to protect their children from abusers, even when the mothers themselves were violently abused. The story led to outrage, including from a member of Congress, and Arlena got a bundle of encouraging letters from people she didn’t know. But her sentence stayed in place.

When Victoria Pedraza read the article, she said she felt déjà vu. She and Arlena were both 21 years old when their worlds collapsed. Both had tried and failed to leave abusive partners, had been turned against their families, had felt like they had nowhere else to go, had not appreciated the danger their children were in. Both were arrested before their children’s funerals had even taken place. Hearing about Arlena made Vicky feel, for once, like she was not the only mother on the planet carrying her particular strains of guilt and grief.

Vicky had been in the article too, a National Guardswoman whose husband, Daniel, murdered her 2-year-old daughter, Aubriana, better known as Bri. Vicky had lied to the police to cover for Daniel, but when she was booked into jail the guards noticed she was covered in bruises. She was the star witness in Daniel’s trial; she took the stand still missing a tooth from when she said he'd thrown a phone at her. After Daniel got life without parole, a jury gave Vicky 20 years, the maximum under Arkansas law, for “permitting child abuse.”

Late last year Vicky won parole. She would be released after only four years locked up. Her case led to a change in the law, too. She was originally due to be registered as a sex offender when she got out, despite the fact that no one at all had sexually abused Bri. The judge had said the law left him no choice. But after a public defender spoke with a state senator, the law requiring sex offender registration for people like Vicky was reversed, by unanimous vote.

I caught up with her earlier this year as she waited out the last few weeks before her release. Vicky was ready to return home, ready to finally fill that missing tooth. But she was also bracing for what the world beyond her jail cell would be like without Bri. “In my mind, she’s still 2 years old,” Vicky told me.

Vicky’s grandmother Carolyn had tried to keep her connected, peppering their daily phone calls and letters with details about her day and the weather and so on. Every Christmas she sent a care package full of goodies that Vicky couldn’t find in commissary — Chips Ahoy, summer sausages, chips. Then, in December 2014, Vicky was called into the prison chaplain’s office, where she was handed a phone. Her mother was on the other line. Carolyn had died of a heart attack.

Vicky would have two graves to visit for the first time after being released. Carolyn and Bri are buried side by side.

Arlena’s next shot at parole arrived a couple months after she turned 30. She had left the kitchen and was now doing landscaping, which included tending to the prison garden: lemon basil, cilantro, chocolate mint. She was coping. With the help of time and some of the classes she had taken, she came to see how Alonzo had bullied her into thinking she was nothing and that her family didn’t want her around. She had learned how to stick up for herself, and how to say no. “I found my worth,” she said.

She tried her best to say all this during her parole interview, in October 2015. Then she waited, through Thanksgiving and Christmas. She rung in the new year with her closest friend on the inside. Drinking kiwi juice mixed with Sprite, Arlena admitted to the friend for the first time that she was there because of something that had happened to her son.

On the morning of Jan. 14, Arlena sat on the floor combing her hair when a call went out over the loudspeaker: “208, report to education.” A man in a button-down and slacks introduced himself as Troy Fox, parole commissioner. He would be voting on her case, and he had some questions. Arlena went stiff with nerves.

Fox told her he believed in the law that put her away. “Your crime is not a joke,” she remembers him saying. (Fox declined to speak with BuzzFeed News about Arlena’s case, and parole board members generally don’t talk about their decisions.)

He asked her what she would do if she ever found herself in another abusive situation. She told him she would get away.

He asked her if she’d like to see some pictures of her son. She said yes, so he pulled out a copy of my article. He asked to see her wrist tattoo of Titches’ name, which he had read about. He asked her why she agreed to be in the article, and she told him she wanted to help women in similar situations.

A couple weeks later, I found out that Arlena had been granted parole. I called her father to hear how they were taking the news, but no one had informed them. He played my voicemail for Arlena. “Are you serious?” she shrieked into the prison payphone. “Are you serious? Are you serious?”

Tondalo Hall hasn’t gotten a reprieve. She was sentenced to 30 years in prison. The man who admitted to breaking their daughter’s bones was sentenced to two. That disparity was so great, it moved thousands of people to sign a petition on her behalf, and inspired a protest on the front lawn outside an Oklahoma parole board meeting. When she applied for clemency, the board seemed sympathetic, granting her a hearing.

But after Tondalo sobbed through a recitation of her failures, the board unanimously denied her. She appears to have no other options, not even the governor, until 2030, when she first becomes eligible for parole. The man who abused her daughter was set free in 2006.

Child abuse cases are often deeply challenging, with shocking details and complex dynamics but vanishingly few third-party witnesses. Inevitably the question arises of who could have done more to stop or prevent the abuse: child services, grandparents, friends — the other parent. Sometimes it’s clear those other parents, most of whom are women, suffered violent physical abuse, too; sometimes it’s murky, or it seems unlikely. Sometimes the law doesn’t care. In many states, the laws that send women to prison for what others did to their children are still in place, and women like Arlena, Vicky, and Tondalo, still face lengthy sentences.

Just recently, a 2-year-old girl named Kinsley Kinner died in Madison Township, Ohio. She had bruises all over her head and upper body. Her 23-year-old mother pled guilty this spring to failing to protect the girl from the mother’s boyfriend, Bradley Young. (He is due to stand trial, has denied the charges, and his lawyers have questioned her account.) The mother, Rebekah Kinner, said he had terrorized her too, punching her when she was pregnant and biting her as a matter of routine. “Part of me wanted to jump up and grab her out of his hands and just take off with her and just leave,” she told a psychologist, according to local news reports, “but everything just goes black … my body wants to move, but I am frozen … I can’t move.”

At Rebekah’s sentencing hearing, her attorney invoked the many traumas she had weathered, and asked the judge to consider her a victim. She got 11 years in prison.

On a blustery February day, after Arlena had received the good news but before she was given a release date, I drove to the Hobby Unit. This time Arlena and I were separated by the window-and-phone dividers you see on television. She wore purple eyeshadow behind her black-frame glasses. It was cold inside, and the jacket over her prison whites swallowed her slight frame.

She rattled off a list of things she wanted to do when she got out, from eating pizza to learning how to drive to one day helping other women stuck in abusive relationships. I asked if she'd let me interview her when she was on the other side, and she said it would be no problem.

Back at home, she was chirpy on the phone, though she still hadn’t quite gotten the hang of texting. She joined Facebook, too, posting about her first meal and using her first Facebook sticker. She deactivated her account, though, once she realized that a search for her name turned up the article.

She told me she was happy to meet up, and we set an appointment. She didn’t make it. I came by the next day, and she promised she’d be around that afternoon. Again she didn’t show. She stopped answering my texts and phone calls. I flew back home wondering what happened.

I called her on a Wednesday evening a few weeks later and she picked up right away. She had just gotten a job. It was in the packing department at an organic dog-food company. “I didn’t even know they had that,” she said, rattling off the flavors they sold — bacon, sweet potato, chicken, cinnamon.

She said she’d been crazy busy trying to get her life back in order. But things were starting to settle down. She suggested we sit down together over an upcoming weekend. Then she went back to not answering my calls or messages.

Roy says she’s still giddy about getting out. He is, too. He told me in April that he'd lost 18 pounds and his blood pressure is much better. He had an idea why that might be.

The two settled into a routine of sorts. Roy wakes up at the crack of dawn as Arlena heads off to her job. In the evening, they cook for each other. Arlena even prepared him a Mexican dish she learned in prison. “I never had none like the way she fixed it,” he said.

Roy said that between work and reconnecting with friends and family, things were still hectic for Arlena. Maybe someday we’ll get the chance to sit down together. But not yet. I never did get to hear about her visit to Titches’ grave on that first day out of prison. That moment remains hers and hers alone.