This is part of a BuzzFeed News Investigation. Other main stories in the series include:

A Six-Year-Old Gets Locked Up

The Dark Side Of Shadow Mountain and related video

A Prescription For Violence and related video

Nothing To See Here

On a cool October evening in 2012, Samantha Trimble walked into the lobby of Millwood Hospital, a low-slung brick building on the side of a road in Arlington, Texas, seeking a free mental health assessment.

A few weeks earlier in the AP world history class Trimble taught, after a kid started acting childish, she put a diaper on his head — something she admits was a bad idea. When administrators heard about it, she was escorted off the property. Worried for her job and her ability as a single mother to support her daughter, she visited her doctor’s office in tears. A physician assistant asked if she wanted to talk to someone at Millwood.

Just after 8 p.m. that evening, a counselor at Millwood asked Trimble if she was having suicidal thoughts. With her pastor beside her for moral support, she replied, “Well, who hasn’t had suicidal thoughts?” She said she had no intention to kill herself but joked, “It’s Texas, it isn’t that hard to get a gun.” They all laughed, she recalled. She said she had no idea that the counselor characterized the line as a plan to commit suicide.

Nor did she know, she later testified in a deposition, that the dozen or so forms he gave her were anything other than standard doctor’s-office paperwork. She signed them and waited for her counseling session.

It was nearly 11 p.m. by the time a staff member walked her down a long hallway. She recalled being startled to see rooms that were filled not with desks but with beds.

A technician rifled through Trimble’s purse for sharp objects and then a nurse told her to strip down to her underwear. It was then, she said, that she realized the doors to the psychiatric ward had locked behind her.

Trimble, who has recently reached a settlement regarding her hospitalization, recalled shaking with fear and “deep, shameful humiliation” as the nurse examined her body, noting the location of any identifying marks. “All you can do,” Trimble said, “is stand there and let it happen.”

The nurse handed her a small cup of pills, and soon she was asleep.

When she woke up early the next morning, she recalled thinking, What the fuck just happened?

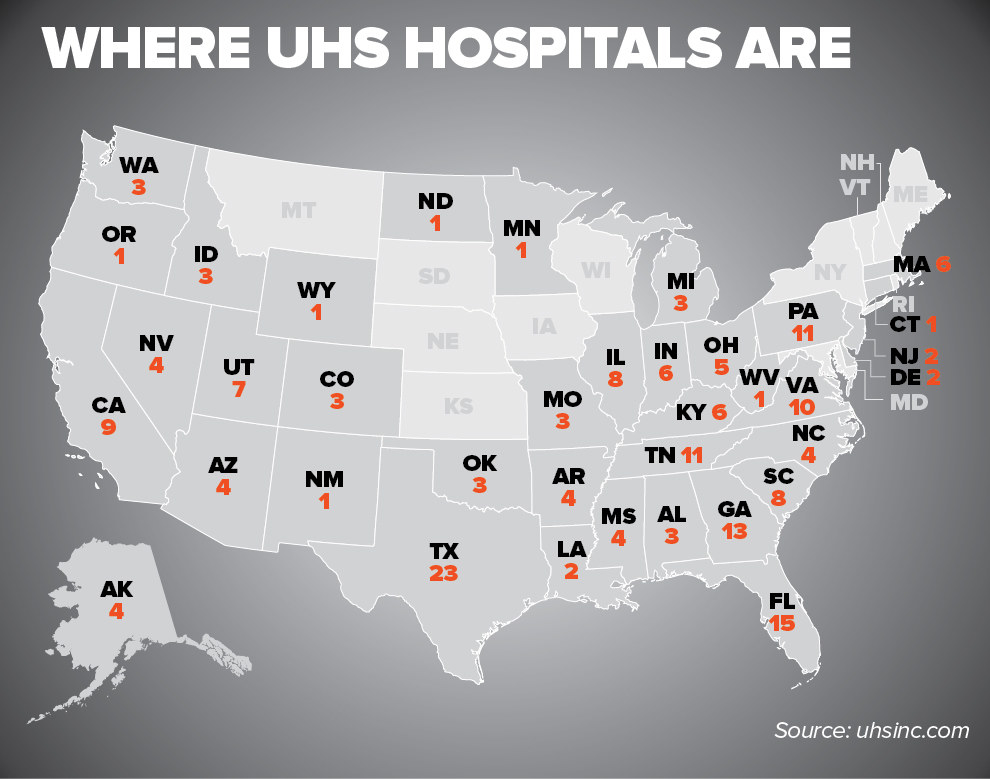

Millwood Hospital is part of America’s largest psychiatric hospital chain, Universal Health Services, or UHS. Its more than 200 psychiatric facilities across the country admitted nearly 450,000 patients last year. The result was almost $7.5 billion in revenues from inpatient care last year and profit margins of around 30%. More than a third of the company’s overall revenue — from both medical hospitals and psychiatric facilities — comes from taxpayers through Medicare and Medicaid.

A yearlong BuzzFeed News investigation — based on interviews with 175 current and former UHS staff, including 18 executives who ran UHS hospitals; more than 120 additional interviews with patients, government investigators, and other experts; and a cache of internal documents — raises grave questions about the extent to which those profits were achieved at the expense of patients.

Scores of employees from at least a dozen hospitals said those facilities tried to keep beds filled even at the expense of the safety of their staff or the rights of the patients they were locking up.

Current and former employees from at least 10 UHS hospitals in nine states said they were under pressure to fill beds by almost any method — which sometimes meant exaggerating people’s symptoms or twisting their words to make them seem suicidal — and to hold them until their insurance payments ran out.

A state-funded 2011 report on one Chicago hospital found “woefully inadequate” staffing levels, a “repeated and willful failure by UHS officials to ensure that their staff were properly trained,” and a pattern of admitting more patients than it had room for “in an effort to maximize financial profit.” Investigators also flagged broader concerns, citing “troubling reports suggesting a pattern of quality of care issues, harm to patients, or major healthcare fraud charges involving UHS-operating facilities in a dozen other states.”

UHS is under federal investigation into whether the company committed Medicare fraud. The probe involves more than 1 in 10 UHS psychiatric hospitals. Three are being investigated criminally — including one facing allegations that it routinely misused Florida's involuntary commitment law to lock in patients who did not need hospitalization.

In March last year, the federal criminal investigation expanded to include UHS as a corporate entity, the company told investors.

The company has said it strongly disputes the allegations of civil or criminal fraud and is cooperating with the investigation. It has not been charged with any wrongdoing.

UHS also disputed BuzzFeed News’ investigation, whose conclusions, it said, “are contrary to the factual record and UHS policies and practices” and which “appears to focus on anecdotal accounts” and “personal perspectives.” It added, “Most of our patients are unable to make the same judgements regarding clinical care and appropriateness of admission and discharge that they might if undergoing other non-psychiatric medical treatment.” (Read the company’s statement here.)

The company “absolutely rejects” any claim that it held patients solely for financial gain. It disputed “the alleged findings and conclusions” in the Chicago report and said UHS hospitals have provided compassionate and high-quality care to millions of patients. Citing the approval of independent regulatory agencies, it said, “Every patient care decision is made with the goal of furthering the best interests of our patients.”

UHS “absolutely rejects” any claim that it held patients solely for financial gain.

After BuzzFeed News began reporting on UHS, the company purchased the domain name uhsthefacts.com. A person with direct knowledge of the matter said the site was intended to showcase stories of positive patient care to counter BuzzFeed News’ investigation.

Many current and former staff spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity, often because they didn’t want to jeopardize future job options.

About 20 employees said UHS operates ethically and provides high-quality care. “I can honestly say in my hospital I never felt like people were being held long after they were due to be discharged,” said Bill Niles, who ran Roxbury Hospital in Pennsylvania for eight years.

“They wanted you to perform with the highest standards,” said Shari Baker, who ran Palmetto Behavioral Lowcountry Hospital in South Carolina until earlier this year. She called UHS “a very ethical organization.”

But scores of employees from at least a dozen UHS hospitals said those facilities tried to keep beds filled even at the expense of the safety of their staff or the rights of the patients they were locking up.

“YOUR JOB IS TO GET PATIENTS”

UHS was founded in 1979 by Alan Miller, who is still at the helm today as CEO and board chair. (Through a spokesperson, Miller declined repeated requests for an interview.) With thousands of patients getting pushed out of public hospitals, and with insurance companies willing to approve hospital stays of a month or more, the 1980s were a boom time for private psychiatric hospitals. But the industry soon got out of hand.

By the early 1990s, when UHS was still a relatively small player, several of the top hospital chains were facing state or federal investigations and a slew of lawsuits from patients. Meanwhile insurance companies tightened their policies, demanding shorter lengths of stay. Unable to sustain the profit margins that investors had grown accustomed to, the chains began to close or sell off hospitals. In many cases, UHS was the buyer.

Today UHS has more than two and a half times as many beds as its nearest competitor. But in its 211 US psychiatric facilities, the company’s name is almost nowhere to be found; one hospital’s development director said including it in marketing materials was “forbidden.” UHS said it does not brand its hospitals, because “it believes strongly that all health care is local” and each hospital takes an individualized approach based on the needs of its community. A list of UHS psychiatric hospitals can be found here.

UHS said the majority of its patients are either transferred from another hospital’s emergency room or dropped off by police who felt they might pose a threat to themselves or others.

The law requires psychiatric hospitals that receive federal money to screen all emergency patients to determine what care they need. If people require emergency treatment, hospitals must care for them, regardless of their ability to pay, until they are stable enough to be safely released or transferred elsewhere. But psychiatric patients — let alone people who have merely come to inquire about a hospital’s services — cannot legally be held against their will unless they pose a clear threat to themselves or to others.

Determining whether patients pose a true risk to themselves or others is hard, psychiatrists said. Clinicians should evaluate thoughts of suicide not in isolation, experts said, but together with a range of factors, including a recent change in the patient’s mental state and whether the person has a plan to act on the thoughts.

Still, this standard gives psychiatric hospitals wide leeway to confine patients to locked wards, an extraordinary power largely withheld from ordinary medical facilities.

At some UHS hospitals, people come not because they're on the brink of suicide but because they have seen advertisements for free mental health assessments. “Highlands can help,” the website for Highlands Behavioral Health in Littleton, Colorado, announces, “but only if you call. To speak with a caring professional or to schedule a free confidential assessment 24 hours a day, 7 days per week, please call.”

Staff members from across the country said such assessments were often not what they appeared to be.

When people called in to ask for help or inquire about services, internal documents and interviews show, UHS tracked what a former hospital administrator called each facility’s “conversion rate”: the percentage of callers who actually came in for psychiatric assessments, then the percentage of those people who became inpatients. “They keep track of our numbers as if we were car salesmen,” said Karen Ellis, a former counselor at Salt Lake Behavioral.

“The goal when you’re on the phone with someone is to always get them into the facility within 24 hours,” said a former admissions employee who worked at three UHS facilities in Texas. “And the reason for getting them into the facility is that once they stepped foot in, they are behind locked doors.”

“People don’t understand,” said a former intake worker at Salt Lake Behavioral Health in Utah. “They think we’re going to diagnose them for anxiety or depression.” She added, “Our goal is to admit them to the hospital.”

UHS told BuzzFeed News it admitted patients based not on financial considerations but only on clinical need: “Decisions regarding admission are made by an attending psychiatrist in consultation with members of the clinical treatment team,” the company said in its statement. Asked about conversion rates, Roz Hudson, a senior vice president of UHS, said that while it’s standard in the industry to track various data points, “it’s not a number necessarily that the line staff are driven by.”

Former admissions and clinical staff told BuzzFeed News that most patients who arrived at their facilities did need treatment. But staff were under pressure to admit not just those people, but almost anyone who had insurance — especially when there were open beds.

“Your job is to get patients,” said a former clinician at Salt Lake Behavioral. “And you get them however you get them.”

Lauren Singer, who worked for six months at the front desk of Colorado’s Highlands Behavioral, said people who were waiting in the lobby for an assessment would ask her what it would entail. “I would frequently get yelled at for overstepping my bounds and telling them too much about the evaluation process,” Singer said. A button behind the receptionist’s desk controlled the lock to the front door of the facility, and, she said, “If someone came in voluntarily, I wasn’t allowed to let them out of the door.”

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Paul Sexton, who ran Highlands at the time, said, “I deny any claims that any patients were ever wrongfully held or detained at Highlands. However, patients are not allowed to leave during an assessment for the safety of the patient, the facility, and the community.” Sexton described that as standard practice across all kinds of psychiatric hospitals.

“Your job is to get patients. And you get them however you get them.”

But three leading organizations strongly contradicted that view. “Absent a reason to be concerned about safety, their own or others', a person who voluntarily presents for an assessment would be free to leave,” said Dr. Steven Hoge, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Psychiatry and the Law. Ron Honberg, a senior policy adviser with the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said that without a court order or a concern that the person poses a threat to himself or others, “it’s not permissible to hold someone.” And Carly Moore Sfregola, a spokesperson for the American Hospital Association, wrote, "They get to leave at any time of their own free will unless someone gets a court order to involuntarily commit the patient."

UHS’s view was supported by its industry organization, the National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems. At first, the group’s head of quality and regulatory affairs, Kathleen McCann, told BuzzFeed News something similar to what the other organizations said: People who walk in for an assessment “are absolutely and totally free to leave” unless they are clear threats to themselves or others. A few hours later, however, she emailed back to “clarify” the position of her organization, of which UHS is a member and whose board will soon be led by the head of UHS’s psychiatric division. (McCann said she informed UHS that she had spoken with BuzzFeed News, but declined to say when.) Patients seeking assessments cannot leave until hospital staff have deemed them safe, she wrote. “This may involve restricting their ability to leave the facility.”

ADMISSIONS

New to the Boulder, Colorado, area, a young accountant named Allison called Centennial Peaks Hospital in June to inquire about outpatient treatment options. Having been diagnosed with bipolar disorder years ago, she wanted to line up support options, just in case. But she recalled being told on the phone that to learn about those options, she had to come in for an assessment. So on her way home from work, she drove to the hospital and sat down with a counselor, who recommended a five-week intensive outpatient program, she recalled. Allison (who asked to be identified only by her first name to protect her privacy) said she told the counselor she didn’t need anything so structured.

The counselor insisted on completing an evaluation anyway, she recalled. Had she thought about suicide in the last 72 hours? Allison answered yes: She had suffered a bout of depression earlier in the week and had been crying at work, the counselor wrote down. But she recalled explaining that such episodes were something she had learned to live with; she had recently changed medications, and since then the dark thoughts had passed, as they always did. Allison even remembered laughing with the counselor during the evaluation. Looking back, she said, “my whole demeanor would tell you I’m okay.”

In her medical record, the counselor noted something similar: “She always goes voluntarily to the hospital if her feelings of SI” — suicidal ideation, or thoughts of suicide — “are too great but says she is not to that point. She stated today has been a good day and that her meds are probably balancing out.”

Nevertheless, the counselor told Allison they were going to hold her against her will. Her evaluation stated, “Patient reported thoughts of suicidal ideation within the last 72 hours, thus she was admitted.”

Allison recalled being given just a moment to email her workplace and call her partner, who was expecting her home for dinner that evening, before being escorted onto the unit. “I didn’t even think that being inpatient was even on the table,” she told BuzzFeed News. “If I would have known that, I wouldn’t have gone in there.”

With enough questions and prodding about suicide, “we can get the person to say: ‘It’s still on my mind.’”

UHS said that out of respect for patient privacy, it could not comment on specific cases without a patient’s written permission.

Every state has its own involuntary commitment law, which allows for patients to be held against their will if they are considered a threat to themselves or others. In Colorado, where Alison was held, the standard to hold someone, even for an initial examination, is high: The threat must be considered “imminent,” meaning current.

Expected to keep beds full, former admissions workers from three UHS hospitals said they learned how to turn even passing statements that people made during assessments into something that sounded dangerous. At Millwood, a former admissions counselor said she was told to “play up the criteria” to get insurers to approve hospitalization. (After a patient was admitted, former clinical staff at Salt Lake Behavioral said, they were trained to “chart to the negative,” emphasizing the most troubling behavior to make the person sound less stable.)

Former intake workers said that suicidal ideation could justify almost any admission. It “was one of those go-to formulas,” said Lacey Wilkinson, who worked in the admissions department at Millwood. “Because that’s the way to make sure everything gets paid for.”

Do you know of problems at a psychiatric hospital? Email psych@buzzfeed.com

With enough questions and prodding about suicide, “we can get the person to say, ‘It’s still on my mind,’” explained a therapist who performed assessments for University Behavioral Health, a UHS hospital in Denton, Texas.

One former clinician at Salt Lake Behavioral said intake assessments might start with the straightforward question “Have you ever thought about suicide?” then move on to the far more hypothetical “If you had a plan, how would you do it?” Almost any answer could then be recorded as a plan.

Allison said that’s what happened to her. The counselor wrote that “OD on pills” was “always her plan,” but Allison told BuzzFeed News she mentioned pills during the assessment only to describe some of the brief thoughts she sometimes had — not anything close to an actual plan. In fact, when she was discharged, the doctor stated, “During the initial two days of hospitalization it was clear that she had no intent or plan of wanting to harm herself.”

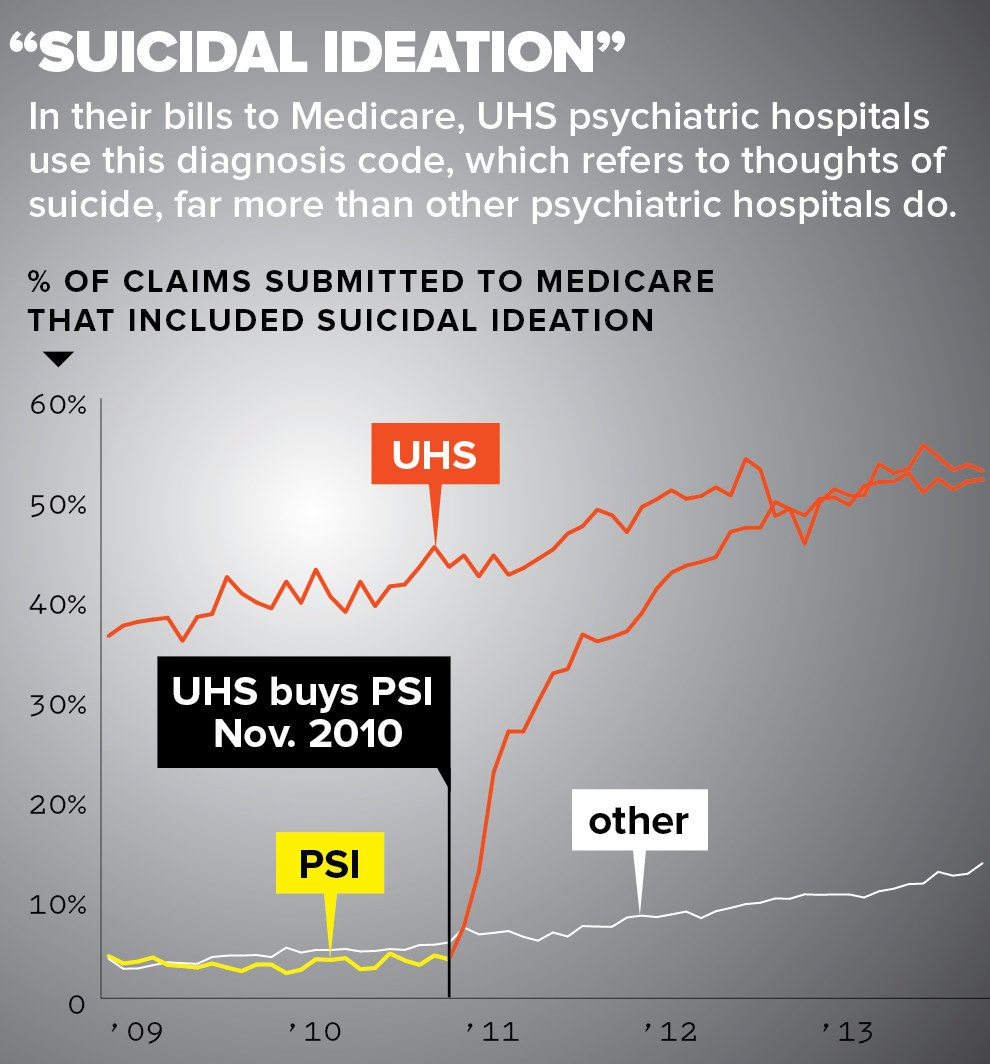

A BuzzFeed News analysis of Medicare claims shows that from at least 2009, UHS hospitals steadily increased the frequency with which they described patients as experiencing suicidal ideation. By 2013, the code for suicidal ideation appeared in more than half of all of the Medicare claims submitted by UHS hospitals. This is four and a half times the rate for all non-UHS psychiatric hospitals. (BuzzFeed News obtained five years of Medicare data from ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative news organization, and a full description of the data analysis is here.)

In the first full year after UHS bought about 100 hospitals from a competitor, Psychiatric Solutions Inc., or PSI, their use of the billing code for suicidal ideation in Medicare claims shot way up — more than sixfold overall.

A manager who worked in billing at one of those hospitals said that after UHS bought it, “we had to adjust to their ways.” Her superiors, she said, “really wanted us to be thorough and build the severity level as much as we could.” She explained that merely being depressed might not support admission. But, she said, “If you’re suicidal, a threat to yourself, you’re more acute and it would better support admission.”

Those statistics, UHS said, were simply evidence of more scrupulous attention to proper coding — not of a higher propensity to diagnose suicidal ideation. Internal and external auditors, the company added, “have never identified any improper assignment of the suicidal ideation as a coding designation.”

More broadly, UHS said, none of its facilities have “received a citation from a regulatory authority alleging that any patient was improperly admitted.”

Some former employees agreed with the company. “It’s definitely a very census-driven atmosphere, but if someone doesn’t meet the criteria, we’re not going to admit them,” said Alisha Powell, a former intake counselor at Highlands Behavioral in Colorado.

Allison was released from Centennial Peaks on her third day, but her partner said she is still living with the effects. “She’s going to be scared to death to ever walk into a facility like that again,” he said.

CORPORATE CULTURE

Several people who ran UHS hospitals said corporate bosses pushed them to cut their hospitals’ staff further and further each year, regardless of the impact on employees’ safety or on their ability to care for the people being admitted.

Each year, hospital administrators presented their budgets to a panel of corporate leaders. And each year, people who were involved with the process say, corporate execs offered the same prescription: Cut more staff.

One former hospital head said that after she presented the annual budget. the behavioral division’s chief financial officer instructed her to cut nine nurses from the staff in order to increase profits. The executive resigned instead.

Staff and patients “were not a priority. The priority was the bottom line.”

“I wasn’t going to fire a bunch of nurses I just hired,” the executive told BuzzFeed News. She later explained, “It would have compromised the quality of care.”

Internal financial reports reviewed by BuzzFeed News show that in 2014, one UHS facility projected a more than 50% profit. Even as the facility had increased revenues in the previous years, it had continued to cut staff.

“It was true greed,” the person who ran that hospital said.

A copy of the 2013 executive compensation plan states that annual bonuses were “designed to reward financial performance in excess of budgeted expectations.” Top hospital executives could make up to 120% of their annual salary based on their financial performance. Only a modest sum in comparison, an additional 20% of their financial award, could be added based on measures of patient care.

Hudson, the UHS senior vice president, said that structure did not undervalue patient care, since all incentives are predicated on the ability of the hospital to maintain its accreditation. “If a facility doesn’t maintain their level of quality, then the bonus plan is irrelevant,” she said.

But for one former hospital administrator, who stayed five years with the company and earned a large bonus, UHS’s message was clear: In this corporate culture, staff and patients “were not a priority,” he said. “The priority was the bottom line.”

PATIENT CARE

Carson Mangines was looking for help when he walked into Highlands Behavioral. The 22-year-old had been cutting himself and was addicted to opiates.

After his admission, a doctor prescribed a dose of fentanyl — a synthetic opioid far more potent than heroin — every three days, for pain relief. His mother, Lianne, recalled that “he was so out of it, he could hardly even speak” when she talked to him a few days into his stay.

One night, a nurse on the overnight shift mistakenly wrote that he was due for a new patch the next day even though he had just had a dose that day, according to a lawsuit the family later brought. A colleague had already complained to administrators that the nurse was “blanket charting,” or documenting things that she had not observed or done, the colleague later told local law enforcement.

The next day, after Mangines’ second fentanyl dose in two days, a social worker wrote that the patient was “overmedicated” and “almost falling out of his chair.” Other staff noted that he was falling asleep and slurring his words and that later he vomited up his medication. No one identified these as signs of opioid overdose.

When Mangines took a broken pencil to his thigh in the shower that night, staff put him in the quiet room. They were supposed to check on him every 15 minutes. His chart says he slept through the night.

But by 9:15 in the morning, his body was in rigor mortis. He had been dead for hours. The autopsy said he died of acute fentanyl toxicity.

“They killed an opiate addict with opiates,” said his mother. “It’s unbelievable to me that could happen.”

According to a summary of surveillance videos from that night, staff members who were supposed to watch for breathing had only glanced in his room from the hallway. The Mangines family settled its wrongful death suit in October.

UHS told BuzzFeed News the dose of fentanyl was “appropriate for Mr. Mangines” and that according to an expert review, his death “was not the result of negligence on behalf of the facility.” UHS did not respond to a request to make that review available.

In statements to police, eight Highlands staff said they were inadequately trained or understaffed. Several interviewed said it was their first job out of school, or their first in psychiatric care. A nurse involved in Mangines’ care told police she had just one day of training at the hospital. And the nurse who gave Mangines his final fentanyl dose told police she had little experience with the drug and that she often had so many medications to distribute in such a short amount of time it was impossible to check if each was being administered properly.

A supervisor told police she had gotten the position just a few months after she received her registered nurse’s license. She said the hospital’s practice of moving new nurses into management roles put patients at “huge risk” and that “pretty much nobody knows what they’re doing.”

It wasn’t just Highlands. A federal report singled out the unit for the most troubled patients at Millwood Hospital, which had just one mental health tech and two nurses. With nurses busy updating charts, admitting patients, and passing out medication, only the tech was left to check in on the unit’s 19 patients every 15 minutes. Staff interviewed said there weren’t enough of them.

Other UHS hospitals in Texas and in Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi have been cited by federal regulators for poor staffing as well. UHS said most of the citations were just for “isolated violations of the facility’s own policies.”

Nancy Smith, who worked as a corporate director of clinical services until 2012, said the company ignored her repeated pleas about insufficient staffing levels.

Her job required her to review patient charts in about a dozen hospitals in four states. She said she often became alarmed because doctors barely met with patients and the notes on charts didn’t match up with the observations of floor staff. She described the number of staff in the hospitals she supervised as so low it was “almost criminal.” It was, she said, “so unsafe.” Yet, she said, her concerns were ignored.

The “minimal, minimal staffing, at the same time that they kept talking quality, just seemed so hypocritical,” she said. “It was an ethical dilemma for me to keep on.”

“UHS categorically denies any assertion that we deliberately and systematically understaff” hospitals, the company told BuzzFeed News. It said its hospitals “frequently went above budget to ensure adequate staffing” and that its facilities have “received numerous quality of care accolades.” As for Smith, UHS said none of the 49 reports she prepared raised issues about staffing levels.

But Smith said, “The reports didn’t get published until they were approved by my boss,” and that her superiors told her staffing concerns were “not your purview.”

Ultimately, Smith decided to retire. The “focus on minimal, minimal staffing, at the same time that they kept talking quality, just seemed so hypocritical,” she said. “I just couldn’t endorse what they were doing, it was an ethical dilemma for me to keep on.”

Four doctors who each worked in different UHS hospitals told BuzzFeed News they juggled such heavy caseloads that they met with patients for only a few minutes each time, not nearly enough time to properly evaluate people with challenging psychiatric conditions.

Among all clinical staff, mental health technicians had the least training but frequently spent the most time with patients, said Smith, the former clinical director. In interviews, more than a dozen techs said they sometimes felt unsafe as they scrambled to monitor the high numbers of patients. One compared the environment to a “war zone.”

Techs were also supposed to lead some group sessions but said those sometimes included nothing more than popping a Hollywood movie in a DVD player, handing out photocopies from workbooks, or just taking patients out for an extra smoke break.

In response, the company told BuzzFeed News, “UHS facilities employ rigorous hiring standards to ensure that only the most qualified candidates are hired.”

Some staff said the situation was frustrating for all involved. ”I’ve never been trained to run a group,” said a mental health technician at Havenwyck Hospital, “so those poor ladies leave my groups more confused than when they come in.”

Kevin Ball, a former tech, said he screened My So-Called Life during group sessions. “My degree was in parks and recreation,” he said, so “I was just as clueless as the kids.”

Mostly, patients “just sat around,” one former patient at Millwood recalled. You “spent most of your day in your room.”

Meanwhile, pressure to admit more patients was so great, staff members said, they did so even if the hospital was already at capacity, thinning resources even further.

“If we didn’t have beds, it doesn’t matter — just go ahead admit them anyway,” Rebecca Palmer recalled being told by her supervisors when she worked at The Ridge in Kentucky.

There would be “every bed filled on the kid unit, teenagers boarding on the child’s unit, and kids sleeping in the dayroom on rubber mats.”

There would be “every bed filled on the kid unit, teenagers boarding on the child’s unit, and kids sleeping in the dayroom on rubber mats,” Palmer told BuzzFeed News. “And also in the seclusion rooms — they would be sleeping in there as well.”

Seclusion rooms are meant to contain patients who have become dangerous. According to federal regulations, the rooms are necessary to protect staff and other patients. Yet staff at four other UHS facilities told BuzzFeed News that there, too, the rooms were repurposed when the hospitals ran out of regular beds.

Federal inspectors noted in 2014 that River Point hospital in Jacksonville, Florida, had more patients than beds. They discovered vinyl mattresses tucked in a closet and on the floors of some patient rooms. A hospital official told regulators the arrangement was “better than throwing a blanket on the floor.”

Speaking for the company, Hudson, the senior vice president, told BuzzFeed News that when there are “limited beds in the entire community,” UHS’s “responsibility is to be responsive to the needs of the patients.” She added, “We’re not abandoning the patient, we’re taking care of the patient.”

In this environment both patients and employees said they often felt helpless. “You just hope there’s no type of crisis,” said Diana Westrick, who worked as a tech at Old Vineyard Behavioral Health in North Carolina. “I’m 5’2” — a small female — and I was left a lot with 12 to 18 patients by myself.”

One doctor who worked at Fairmount Hospital in Philadelphia said the culture of the hospital and the heavy patient loads were “eating my soul.”

“That was the worst clinical experience that I had — and I worked at a prison at one point,” she said. At UHS, “we were saying to loved ones that we’ll help them, and we didn’t have nearly enough resources.”

“I WOULD LIKE TO GO HOME”

When Trimble, the teacher who went to Millwood Hospital for a free assessment, woke up the next morning, she noticed a plastic hospital bracelet had been placed on her wrist. Still wearing her clothes from the previous day, she recalled, she walked toward the nursing station at the end of the hallway, passing one patient drooling and another hitting himself in the face. She had been admitted to psychiatric intensive care, the unit for the most severe patients.

"I would like to go home," she told a nurse.

She said she was not aware of it at the time, but one of the documents she had signed the previous night granted her consent to be hospitalized. Now the nurse said they couldn't release her without a doctor's permission. Hospital records show that at 6:05 that morning, Trimble filled out a form requesting to be let go. Texas rules say that within four hours of filling out that form, patients must be discharged, unless a physician finds cause to hold them against their will. A doctor instructed the hospital to hold Trimble. It was 4:30 in the afternoon by the time she met with that doctor, the first one she had seen since she was admitted.

At the meeting, which Trimble estimates lasted about 10 minutes, the doctor denied her request to go home. "You've been converted to an involuntary commitment," Trimble recalled being told.

Records show that her treatment plan listed an estimated stay of five to seven days, in line with the five days Trimble’s insurance company had approved.

Trimble called her mother to help get her out. Carolyn Velchoff drove down to the facility, but staff there refused to release Trimble. So Velchoff called the FBI: “My daughter has been kidnapped,” she said she told an agent. (A spokesman for the FBI office in Dallas declined to comment on whether it was contacted.)

On the afternoon of her third day at Millwood, Trimble called the local police. An officer came to investigate, but the hospital refused to produce any paperwork to support Trimble’s admission. A supervisor told the officer “not to interfere with medical staff,” the police report noted.

“Based on officer’s training and experience, officer did not believe comp was danger to herself or others,” the report stated, referring to Trimble. It also stated that the officer believed that the hospital was violating Trimble’s rights. But after an hour and a half at Millwood, even the police officer was unable to win her release.

KEEP THEM IN

Two dozen current and former employees from 14 UHS facilities across the country told BuzzFeed News that the rule was to keep patients until their insurance ran out in order to get the maximum payment.

Three former heads of UHS hospitals said their divisional vice president, Sharon Worsham, repeated a mantra: “Don’t leave days on the table.”

“If an insurance company gave you so many days, you were expected to keep the patient there that many days,” said Rick Buckelew, who ran Austin Lakes Hospital in Texas until 2014. It was a “common practice” that was openly discussed in regional conferences as well as phone calls with hospital executives, which Worsham led, he said. Buckelew added that he did not follow this practice and that the operations he oversaw at his facility were appropriate. Worsham said she and Buckelew did not have regular discussions “about days on the table relating to Austin Lakes.”

Employees of UHS hospitals from Utah to Pennsylvania said this message trickled down to staff and doctors through “flash” meetings, the daily gatherings in which administrators ran through the list of patients in the hospital, discussing treatment and discharge.

In its statement, UHS said it “rejects any accusation” that any of its hospitals improperly manipulated length of stay “to increase financial performance.”

It said “discussion of ‘days on the table’ was about patient safety concerns.” If an insurer had determined that a patient needed a certain number of days, the company said, “it was appropriate to evaluate — with the relevant physician and clinical team — whether premature discharge was in the patient’s interest.”

Karen Johnson, UHS’s senior vice president of clinical services, praised flash meetings, describing them as an opportunity to “make sure we’re prepared to take care of each patient from a care perspective and look at each discharge to make sure the patient has a viable and manageable discharge plan so that they can transition safely” back to the community. Several former executives who ran UHS hospitals agreed that flash meetings focused on medical care.

“If an insurance company gave you so many days, you were expected to keep the patient there that many days."

Yet more than 20 executives and managers who attended those meetings in 12 states said their purpose was also “to review how many days they have and to try to use up those days,” as one former hospital head put it.

Two people who worked at Highlands Behavioral in Colorado when Paul Sexton, then the head of the hospital, led the daily flash meetings, said he ran down the list demanding an explanation for each early discharge. “Why are they going home? They still have days left,” one of the staffers recalled him saying. (Sexton told BuzzFeed News “the purpose of such discussions was clinical. Any financial benefit was secondary and only applied if the patient met clinical criteria.”)

After flash meetings, hospital managers such as Mark Tippins at Salt Lake Behavioral said they were expected to pass the message along to doctors. He said he chose an understated approach. Referring to patients who still had days left, he recalled saying, “Second floor” — the hospital’s administrative offices — “wants me to see what we can do to get this patient to stay longer.”

For patients, the experience could be bewildering, even terrifying. “It was pretty common to get women in the unit who were like, ‘Why am I here? I don’t need to be here,’” recalled one former manager at Salt Lake Behavioral. “We were just encouraged to talk them into staying until as long as insurance would cover.”

She added, “Whatever manipulative strategies we could use, we were encouraged to.” If the patient was a mother, she said, employees might threaten to call child protective services and have the patient’s children removed from her care.

UHS said the hospital “does not use threats of any kind” to try to “force patients to stay against their will.”

At Highlands, a staff psychiatrist wrote to Worsham, the corporate divisional director. “I am, in particular, deeply disturbed about the efforts to extend lengths of stay,” he wrote in a 2014 email reviewed by BuzzFeed News. “Doctors are publicly shamed by asking them to justify discharging a patient ‘early’ before the end of their insurance authorization.”

Two weeks later, Worsham responded by asking that he speak with the medical director of his hospital about his “perspective.” Worsham told BuzzFeed News she oversaw hundreds of doctors and doesn’t remember that particular exchange. She denied “any allegations that clinical decisions have ever been made for purely financial purposes.”

In a draft of the hospital’s 2014 strategic plan, which he said was not presented to UHS, Sexton described extending patient stays as a means to meet financial goals. Sexton proposed that the hospital “develop and implement a plan to increase average length of stay” as a means to meet financial goals. Other executives also told BuzzFeed News it was one of the strategies they used to meet their budgets.

After UHS learned that BuzzFeed News had obtained a copy of this strategic plan, a lawyer on behalf of the company demanded the return of it and any other internal documents. BuzzFeed News declined. Sexton later wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News that length of stay is a common industry metric and “any plans or efforts to increase length of stay at Highlands never involved keeping patients beyond a discharge date as determined by the attending psychiatrist.” He added that he believed UHS was an “ethical company.”

At least five hospitals, including Highlands, have been cited by federal regulators for violating a patient’s right to be discharged or holding a patient without the proper documentation. UHS said these citations were procedural errors that “do not constitute an intent or practice to hold patients who do not meet clinical criteria or delay discharges for financial reasons.”

10-DAY STAY

One hospital acquired by UHS — River Point, in Jacksonville, Florida — took an extraordinary approach to determining how long people should be hospitalized: At the instruction of Gayle Eckerd, the hospital’s top executive, River Point established 10 days as the “guideline” for how long to keep patients.

Ten days is the length of time for which Medicare will pay the full daily rate without requiring the hospital to get approval. And according to eight current and former River Point employees and investigative documents, the hospital’s true goal was to maximize government payments.

One UHS hospital established 10 days as the “guideline” for how long to keep patients.

Beyond the trauma of being confined against their will — and the disruption to their lives and jobs — patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses faced dire consequences from this approach. Medicare grants only 190 days of inpatient psychiatric treatment over the course of a patient’s entire life. So spending those days if they weren’t actually needed amounted to “taking away care that they’re going to need later and they’re not going to have,” said a former discharge planner at Highlands Behavioral.

Eckerd, who ran River Point until 2014, kept close track of the facility’s average length of stay, which was displayed on a board in the conference room where flash meetings were held. The higher the number climbed, current and former staff said, the happier Eckerd seemed. (Eckerd died suddenly that year.)

“Flash meetings were basically to discuss why patients were leaving before day 10,” said a former River Point manager. If they left sooner, the manager continued, “you were questioned: ‘Why were they leaving?’”

Eckerd's effort succeeded. In early 2009, the year she took over as CEO, just 37% of Medicare patients stayed for 10 days or more. By early 2010, the year UHS bought the hospital, that rate had almost doubled to more than 70%. UHS kept Eckerd on to lead the facility, and the rate stayed high for years. Asked about that increase, Johnson, the UHS senior vice president of clinical services, said that River Point was “providing care that’s necessary for the patients.”

Do you know of problems at a psychiatric hospital? Email psych@buzzfeed.com

Now, however, federal investigators are probing whether River Point achieved those numbers in part by abusing the courts to hold patients against their will.

In response to questions about River Point’s operations, UHS's Hudson, who oversaw Eckerd, told BuzzFeed News that all UHS’s hospitals “have a responsibility to the safety of their communities” and “we do that very well at our hospitals and River Point does it very well.”

“Eckerd knew that medical research shows that short stays are associated with high readmission and suicide rates so she established a 10-day guideline with the goal of providing patients with the medically necessary care they needed,” UHS said in its statement to BuzzFeed News. It added that this was not a one-size-fits-all requirement.

An unemployed veteran, Michael Pruitt said he was feeling hopeless when he called a help line for veterans in March 2014. Police brought him to River Point under the Baker Act, a Florida state law that allows authorities to send someone for an involuntary psychiatric examination for up to 72 hours. During his stay, federal regulators would visit River Point in response to an investigation into allegations that the hospital was improperly holding people for 10 days in order to maximize insurance payments.

According to the hospital, Pruitt had told the VA he was having thoughts of killing himself. When he arrived at River Point, however, records show he repeatedly said he wasn’t suicidal. When those 72 hours were up, he expected to go home. But the hospital would not release him.

Instead, the hospital filed a petition in court to hold him longer. Just filing that petition gave the hospital the legal right to detain Pruitt until he had a court hearing. Those petitions are meant to be used only in extreme cases. But at River Point, three former therapists told BuzzFeed News, filing them became standard practice.

“The rule of thumb is: If you came in under a Baker Act, we’re going to file a petition, and then we figure out what the days situation is” with the insurance company, one former therapist told BuzzFeed News. “If they didn’t have insurance they were discharged.” But if they did have coverage, the former therapists said, filing the petition would allow River Point to hold the patients in the hospital, and to keep the insurance money coming.

A BuzzFeed News analysis of court records shows that in 2009, the year before UHS bought the hospital, it filed 238 petitions for involuntary commitment. Four years later, that number had grown to 1,362 — an increase of more than 470%.

UHS said “any claims that the Baker Act process was used improperly in any way at River Point are completely unfounded.” It attributed the increase in the number of petitions largely to increasing the number of beds for elderly patients, “who commonly have challenging mental health issues requiring involuntary commitment.”

Therapists who filed these petitions said the doctors gave little justification for holding the patient — sometimes just a few words with almost no context.

Public defenders who represent Baker Act patients noted this as well. The petitions filed by River Point “were often legally insufficient and lacking in supporting documentation,” said Stephanie Jaffe, a public defender in Duval County.

Four days after Pruitt’s admission, the federal regulators who were looking into River Point’s practices reviewed his records. He told them he was being held against his will.

According to their report, his doctor could not explain why Pruitt needed to be involuntarily hospitalized. The documentation in his chart did not support his listed diagnosis. When asked about Pruitt’s diagnosis, the doctor told investigators that he still wasn’t sure. “Probably a mood disorder. I’ve only known him a short time…maybe bipolar affective disorder,” the report quotes him as saying. In response to questions about his symptoms, the doctor answered that his patient was “angry, irritable and mildly hostile.” UHS told inspectors it held Pruitt to ensure that he was safe.

The inspectors found that River Point had failed to properly evaluate Pruitt for discharge, and they told the hospital to correct its standards.

In April 2014, because of the larger investigation that brought the inspectors to River Point in the first place, the government suspended Medicare payments to River Point. UHS told BuzzFeed News it has “consistently disputed and refuted the purported basis of the payment suspension.” The state of Florida followed with a suspension of Medicaid payments.

DON’T LET THEM IN

In September of last year, Kevin Burns felt the urge to hurt himself again. Just two days before, he had been released from a UHS psychiatric hospital, Suncoast Behavioral Health in Bradenton, Florida. But having battled schizophrenia and depression for much of his 32 years, Burns knew the warning signs, he said — the frightening and overwhelming impulse to cut himself. So he walked back to Suncoast.

The hospital barred the door, refusing even to let him in for an evaluation, something that many UHS hospitals, including Suncoast, advertise as a free service. The receptionist called the police.

Burns walked behind the hospital to a nearby Walmart, where he bought a package of razors. Before the cashier had even handed him back his change, he popped the package open and made several quick, deep cuts to each wrist.

“I was begging for help, and that was the first logical thing I could think of to do,” Burns told BuzzFeed News.

Florida’s health care agency investigated Burns’ case. The hospital told state investigators he had threatened to hurt staff — a charge Burns denies — and that two employees later vowed to leave if he were allowed in. Investigators ruled that the hospital had violated emergency treatment laws. In the end, Suncoast admitted it had violated state law, and the agency fined the hospital $1,000.

At Suncoast, said three former employees, admissions decisions were simple. If the person has insurance, why haven’t they been admitted? If they don’t have insurance, why are they still here?

“We had people with medical needs that we could not meet,” said Palmer, the former intake employee who worked at UHS hospitals including Suncoast. There, she said, the hospital’s leadership “would pressure us to accept them, just because they’re paying customers.” On the other hand, “If they couldn’t pay, ship them out.”

In interviews, staff from many hospitals confirmed that despite these goals, UHS did accept uninsured patients, such as those dropped off by police or those who needed emergency treatment. Staff also said that clinical staff and doctors could advocate to keep some patients past the end of their insurance payments if the need seemed great enough.

But former executives said they would get pushback from superiors for admitting too many uninsured patients. “If they all didn’t have a payer” — an insurance plan — “the next day you’d get a call from your corporate regional person: ‘Why are you admitting ‘self-pay’ payers?’” said a hospital executive who left the company in 2014. “If someone is self-pay it’s well known that’s a no-pay.”

Another former executive, who ran a UHS hospital for five years, said the pressure came right from his corporate superiors: “You were told to do things to eliminate uncompensated care, all the way down to basically lying and saying that you didn’t have a bed.”

That happened at Suncoast too, Palmer said. Uninsured walk-in patients sometimes waited for hours in the lobby as intake workers looked for another facility to transfer them to, explaining that there was no bed available. Sometimes there really wasn’t a bed available, Palmer said, but “sometimes it wouldn’t be true.”

A former Suncoast manager who is also a licensed nurse said she found the hospital’s management so unethical that she resigned.

“You have insured people who didn’t always need treatment getting admitted,” and “uninsured people not being hospitalized when they should be.”

None of the Suncoast workers interviewed knew about Burns’ case specifically, and it couldn’t be determined if insurance factored into the hospital’s decision to lock him out. But in reviewing Burns’ records, BuzzFeed News found something not mentioned in the state’s investigation. The previous time Burns was hospitalized, his Medicaid provider had declined to pay for eight of the 13 days.

UHS said any assertion that its hospital turned away emergency patients in need of care “is categorically false.” It said it provided more than $85 million of uncompensated care to patients across its psychiatric division last year.

“If UHS had a practice or policy of deflecting uninsured patients, there would be hundreds if not thousands” of citations for violating federal emergency treatment laws, it said, while in reality it has received only an “exceptionally small number of citations” over the last five years.

But more than a dozen current and former employees also said that UHS pushed employees to make sure that uninsured patients were discharged as quickly as possible — or better yet, not admitted at all.

Ellis, the counselor who worked in the admissions department at Salt Lake Behavioral Health, said the practice posed a dilemma: “On the one hand, you have insured people who didn’t always need treatment getting admitted. But the flipside is that you have uninsured people not being hospitalized when they should be.”

“People didn’t get admitted because they met the criteria,” she said. “There was always a financial consideration.”

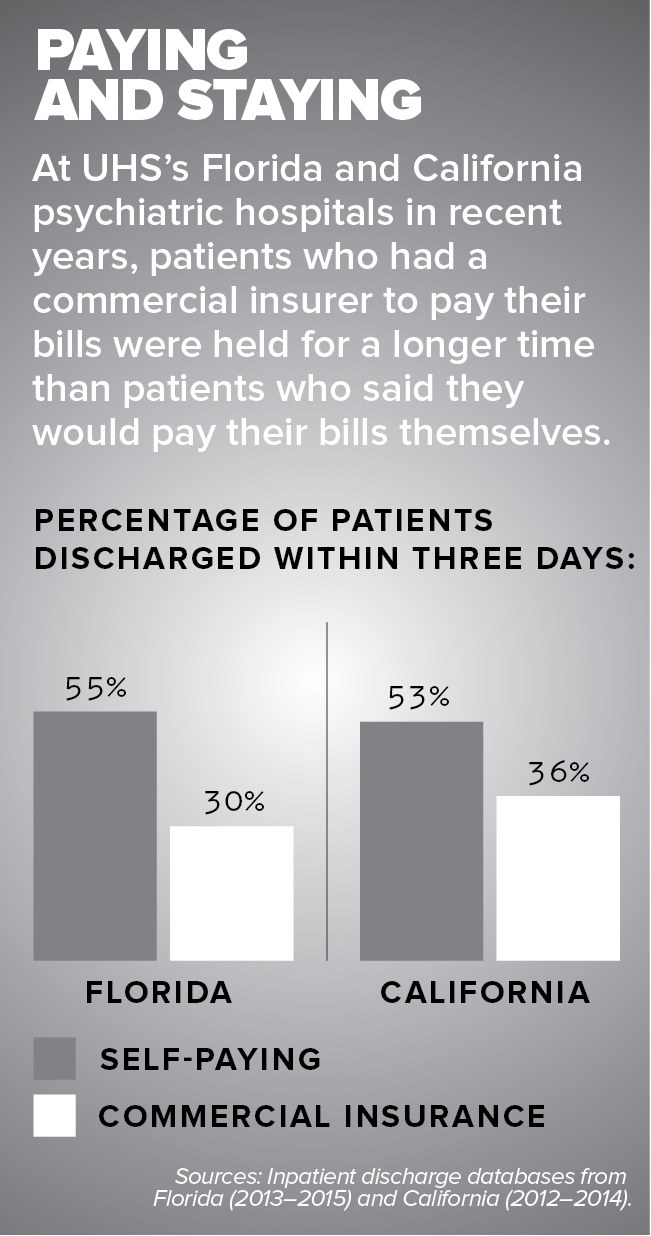

At the company’s Florida hospitals between 2013 and 2015, 55% of self-paying patients were discharged within three days, compared with just 30% of patients with commercial insurance. (Other for-profit psychiatric hospitals had a similar disparity, but not-for-profits showed almost no difference.) In California, a similar pattern was found.

Asked about this discrepancy, UHS's Johnson said a patient’s length of stay is based on their individual treatment plan. She disputed that a patient’s insurance was a factor and said a discharge is “a clinical decision; it’s not a business decision.”

VISIBLY UPSET

At Millwood Hospital, where Trimble, the AP history teacher, was held against her will, the police officer who answered her call had no success getting staff members to show him her records. Eventually he left. He wrote in his report that “patient rights stated that comp” — complainant, meaning Trimble — “could look at records but staff refused to show records to comp or officer. Comp was visibly upset.”

Trimble saw her doctor again the next day. The doctor observed that Trimble was “writing down each and every word and asking about her rights,” behavior the doctor characterized as “very paranoid.” But in the discharge note, the doctor wrote that she had no reason to hold Trimble against her will, because she was not suicidal or homicidal.

Trimble was released later that day. She has since sued the hospital for negligence and false imprisonment. In court papers, UHS said Trimble had been properly admitted and treated, based on physician orders.

She says she fought back after her release because “I began to realize what happened to me was wrong,” she said. “It was a shame and humiliation that I’ve never experienced in my life.”

Last month, she agreed to settle the case. UHS won’t reveal the terms of the settlement, but the company maintains it did nothing wrong. ●

Jeremy Singer-Vine and Kendall Taggart contributed data analysis to this story.