The first thing Latricia Chance saw when she walked up to the apartment that October morning was a toddler, alone and shoeless, eating cereal on the doorstep. It was her friend Arlena Lindley’s 3-year-old son, Titches. Chance said hello. Titches, his mouth full of food, said nothing.

Inside, she greeted Lindley and her boyfriend, Alonzo Turner. Chance knew the couple had gone through trouble in the past, and something seemed off between them now — it just wasn’t clear what. Then Turner stepped outside and dragged Titches into the living room. Titches had soiled his light-blue pajama pants.

Turner, a 6-foot-2-inch, 220-pound factory worker, ordered the toddler to bend over and touch his toes. He whipped him with a thick leather belt, then threw him against the wall. Titches hit his head so hard that he spat out some of his breakfast. Turner took Titches by his neck and wiped his face in the half-eaten cereal. With Titches on his back and crying, Turner pressed his foot to the boy’s chest. Then he picked him up, dragged him to the bathroom, pushed his face into the toilet, and flushed.

Turner turned to Lindley, warning her that if she tried to take Titches out of the house he would kill her. Chance could see the terror on Lindley’s face. Yet Lindley spotted an opening, grabbed hold of her son, and made for the front door.

She was too slow. Turner snatched the boy from her arms and, still holding the boy, slammed the door shut on Lindley and Chance, locking them outside. Stunned, they withdrew to figure out what to do.

By the end of the day, Titches would be dead, and Turner would be arrested for his murder. Prosecutors would charge Turner with assaulting Lindley too, noting that she was “very afraid” of him.

Yet they would also deem Lindley a criminal. Even though Lindley had tried to rescue her son, they would prosecute her for failing to protect him from Turner.

Her sentence: 45 years in prison.

Lindley’s case exposes what many battered women’s advocates say is a grotesque injustice. As is common in families terrorized by a violent man, there were two victims in the Lindley-Turner home: mother and child. Both Lindley and Titches had suffered beatings for months. But in all but a handful of states, laws allow for one of the victims — the battered mother — to be treated as a perpetrator, guilty not of committing abuse herself but of failing to protect her children from her violent partner.

Said Stephanie Avalon, resource specialist for the federally funded Battered Women’s Justice Project, “It’s the ultimate blaming of the victim.”

No one knows how many women have suffered a fate like Lindley’s, but looking back over the past decade, BuzzFeed News identified 28 mothers in 11 states sentenced to at least 10 years in prison for failing to prevent their partners from harming their children. In every one of these cases, there was evidence the mother herself had been battered by the man.

Almost half, 13 mothers, were given 20 years or more. In one case, the mother was given a life sentence for failing to protect her son, just like the man who murdered the infant boy. In another, the sentences were effectively the same: The killer got life, and the mother got 75 years, of which she must serve at least 63 years and nine months. In yet another, the mother got a longer sentence than the man who raped her son. In one more, a father fractured an infant girl’s toe, femur, and seven ribs and was sentenced to two years; for failing to intervene, the mother got 30.

At least 29 states have laws that explicitly criminalize parents’ failure to protect their children from abuse. In Texas, where Lindley lives, the crime is known as injury to a child “by omission.” In other states, it goes by “permitting child abuse” or “enabling child abuse.” In addition, prosecutors in at least 19 states can use other, more general laws against criminal negligence in the care of a child, or placing a child in a dangerous situation.

These laws make parents responsible for what they did not do. Typically, people cannot be prosecuted for failing to thwart a murder; they had to have actually helped carry it out. But child abuse is an exception, and the logic behind these laws is simple: Parents and caregivers bear a solemn duty to protect their children.

If a violent partner threatened her child, “I would sacrifice my life 10 times out of 10,” said Carmen White, the Dallas prosecutor — and mother — who pressed charges against Lindley. The law provides justice for child victims, she said, and it sends a message to mothers about their duties.

Only a few states provide an exception for parents who feared for their safety at the time the violence occurred. In some of these states, that exception is narrow or limited, leaving battered women open to prosecution.

Prosecutors often use the violence a mother endured as evidence against her. Since she was battered, they sometimes argue, she should have left the relationship, taking herself and her child to safety.

Advocates have tried but failed to compile national figures on how many women get prosecuted and sentenced under these laws. BuzzFeed News created its tally by focusing on 29 states that allow for sentences of at least 10 years. But because of limitations in the data provided by different states, BuzzFeed News’ tally is conservative; the actual number of cases is likely higher.

Then there are cases of women sentenced to a decade or more but where it’s difficult to determine whether they were victims of partner violence. BuzzFeed News found 45 such cases over the last decade. Often, the abuser and the mother who didn’t stop the abuse pled guilty, leaving little detail in their court files about what actually happened. Domestic violence advocates suspect many of these women were battered too, saying that women who’ve suffered abuse often conceal it, even through weeks or months of counseling. "I know in my heart that there's more out there," said Laurel Mohan, executive director at the Battered Women’s Legal Advocacy Project in Minnesota.

(BuzzFeed News’ methodology and full list of cases can be found here.)

Where there is evidence of the women being battered, the case files describe them being punched, throttled, kicked, whipped, or raped — often in combination — at or around the time their assailants were doing the same to their children. “My husband took full possession of me and my life,” a mother in Tennessee told the court right before her 15-year sentence was handed down.

Domestic violence advocates say these cases signal a deep misunderstanding of what it means for women to be trapped in abusive relationships. Many such women fear alerting authorities, because doing so can provoke their partners to extreme violence. Moreover, authorities often fail to protect battered women and their children. Advocates also say that imprisoning these women serves little purpose and deprives any surviving children of their mother.

The laws against failing to prevent child abuse are written to cover both fathers and mothers. And, in fact, women perpetrate 34% of serious or fatal cases of physical abuse of children, according to the latest congressionally mandated national study of child abuse. But interviews and BuzzFeed News’ analysis of cases show that fathers rarely face prosecution for failing to stop their partners from harming their children. Overwhelmingly, women bear the weight of these laws.

BuzzFeed News found a total of 73 cases of mothers who, regardless of whether they were battered, were sentenced to 10 years or more. For fathers, BuzzFeed News found only four cases.

White, Lindley’s prosecutor, couldn’t recall prosecuting any fathers for failure to protect from physical abuse.

“Mothers are held to a very different standard,” said Kris McDaniel-Miccio, a law professor at the University of Denver whose expertise is domestic violence. She said that the lopsided application of these laws reflects deeply ingrained social norms that women should sacrifice themselves for their children.

From a different perspective, White agreed, saying that severe punishments generally fit “what people believe” should happen to mothers who shirk their duty to their children.

Aside from conceptions of motherhood, McDaniel-Miccio said that many people — and, by extension, many judges and juries — still don’t grasp the answer to a question at the core of so many of these cases: Why didn’t she leave him?

Shortly before Alonzo Turner and Arlena Lindley began dating, a young woman named Michaelyn Haynes and her sister were sleeping, they told police, when they awoke to a noise and found Turner in the kitchen. He and Haynes had dated, and he told her he was there to get money he had given her several months earlier. He shoved Haynes. She fell against her sister, who was pregnant. Turner then grabbed a pair of shoes and a cell phone and left.

When police officers arrived, they found a ladder up to the kitchen window, which had been pried open. Turner was charged with burglary.

About three weeks later, Turner again climbed through Haynes’ kitchen window, she told police. This time, he ordered her to come outside and speak with him. When she refused, he grabbed her by the neck and cupped her mouth with his hand, forcing her out of the house.

A neighbor, Mark Page, overheard the ensuing struggle and demanded that he let her go. He told police that Turner replied, “Stay the fuck back or I’ll kill her.” Page pulled a Taurus .38 Special revolver and fired a warning shot into the ground. But Turner still did not back down, continuing instead to threaten to kill Haynes. Page didn’t want to shoot, so he pulled out a knife and stabbed Turner in the leg. Only then did Turner flee.

In an interview, Haynes said that even now, with Turner safely behind bars and their relationship long over, she has trouble trusting people. “I’m still scared to this day,” she said.

Police records first refer to Turner’s actions as “aggravated kidnapping,” a felony. Ultimately, however, he was charged with “unlawful restraint,” a misdemeanor. The police report states that the incident was not a family violence issue.

Both the burglary and unlawful restraint charges took months to wind their separate ways through the system. Two weeks before he killed Titches, Turner was found guilty of burglary and sentenced to probation. He never stood trial for the unlawful restraint charge, which prosecutors dropped once he pled guilty to murder. Turner declined to be interviewed for this story.

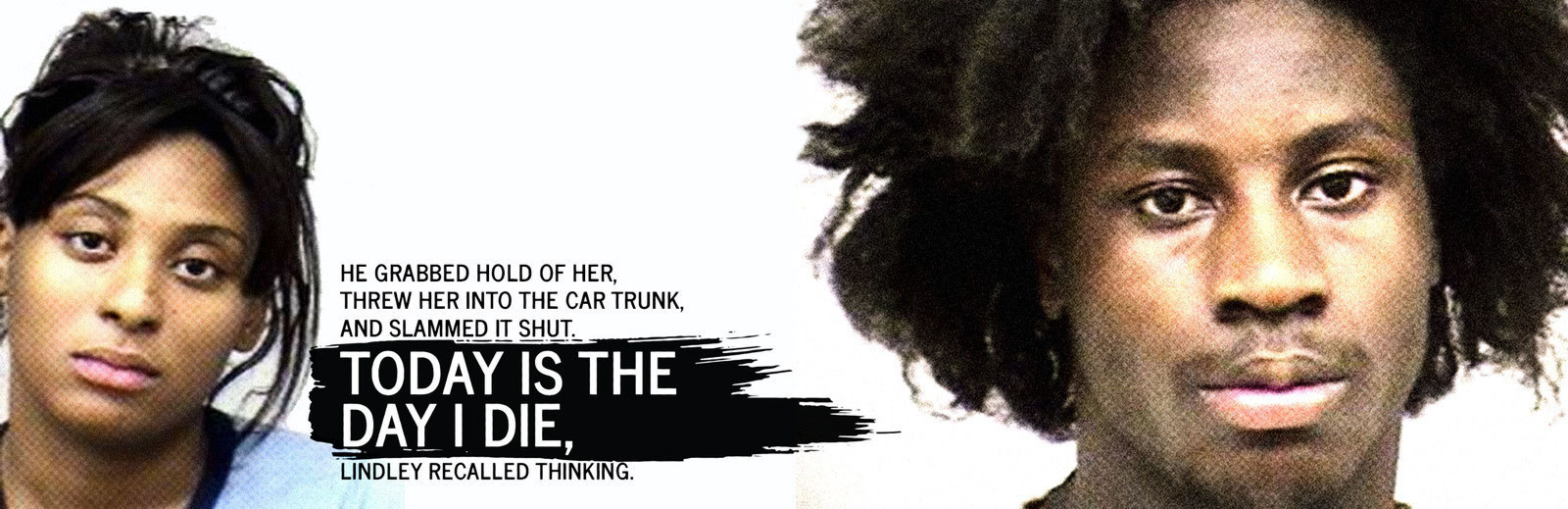

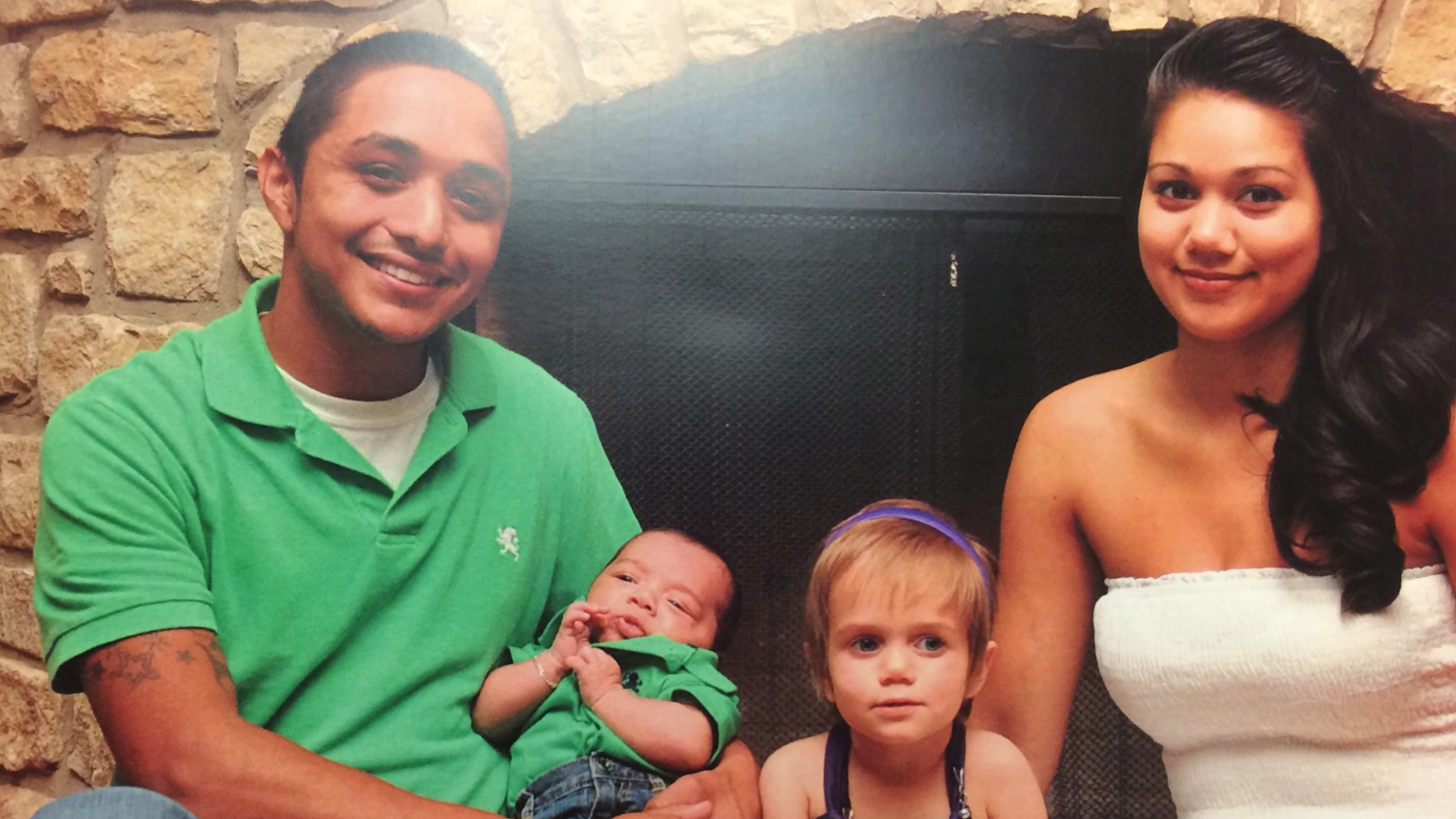

He and Lindley started dating in early 2006, when he was 18 and she was 20. He seemed sweet, Lindley said in an interview. Sitting in the prison cafeteria, supervised by a guard, she recounted the course of their eight-month relationship, which is also covered in court documents.

Early on, he took her to restaurants and the local go-kart track, and he bought toy cars for Titches. When he found out that Lindley’s ex had called her, he demanded that she tell him that she never again wanted to speak to him. But he didn’t hit her for the first few months they were together.

By the time they were both arrested, however, he had punched her, pulled her hair, and sat on her. “He choked me all the time,” she said, once so hard that he lifted her off the ground. Turner weighed 50 pounds more than Lindley, who is 5 feet 4 inches and wears glasses. One time she tried to call the police on him, but he grabbed hold of her by the hair and hurled her outside.

"He would say he would never hit me in the face, because he gotta look at me," Lindley said, but anything else seemed in bounds. Turner didn’t even care if other people saw. He once shoved her down at a parking lot outside a laundromat, the gravel stinging her palms as she broke her fall.

Another time, they were in the apartment, and Turner had some friends over. Turner owned a gun, and Lindley was nervous about it being in the home with Titches around, so she took out a bullet and threw it outside into the dark. Turner found out and ordered her to comb the grass until she found it. One of his friends offered her a flashlight, but Turner refused to let her use it. When she failed to find it, he ordered her to strip naked and continue searching on her hands and knees.

Lindley grew more and more afraid of Turner. “He just snaps,” she said in court. “You never know how he is going to be when he wakes up in the morning.”

One evening, after he used a belt on Titches, Turner fell asleep. Lindley quickly packed her bags and got ready to usher Titches out the door. Turner’s young nephew was in the home, though, and asked where they were going. She told him they were going to the store. He asked to come with her, but she said no and set off walking in the direction of a friend’s place. They hadn’t gotten more than a few hundred feet when Turner caught up to her. He forced Titches from her arms, gave him to the nephew, and, clutching Lindley by the shirt, pulled her back toward the apartment.

“I done tried to leave plenty of times,” she testified, but he “actually called and threatened to kill my family.”

The last time Lindley tried to escape, she hitchhiked to the home of a friend, who then gave her a ride to her father’s house. She didn’t hear from Turner for a couple of days. Then he called her cell phone, saying that if she was truly leaving him, he wanted back some stuff he had given her. He came by her father’s house, and she brought down a boom box he had bought her.

As she turned to go back inside, he grabbed hold of her, threw her into the car trunk, and slammed it shut. Today is the day I die, Lindley recalled thinking.

She lay in the darkness, waiting for his next move. After a few minutes, he popped the trunk back open, telling her, "I ain't gonna do you like that." Lindley was terrified. But, she said, she also didn’t want to bring trouble into her father’s house. She moved back in with Turner.

Texas lawmakers didn’t seem to have cases like Lindley’s in mind when, in 1977, they created the state’s child abuse “by omission” law. During a brief committee hearing, just one witness was called, a county prosecutor. Asked what kinds of situations the omission law would cover, he cited parents who fail to feed their children, causing them to starve. He did not mention a woman failing to stop her violent partner from abusing the child. The bill passed easily.

Yet prosecutors used the law against battered women as early as 1983, when an El Paso man named Keith Webb murdered his 6-year-old stepson and buried him in the desert. It emerged that Keith had also been abusing his wife June for years. She had reported him to the police several times, but he was never prosecuted. June was convicted of child abuse by omission because, on two occasions after Keith hurt her son, including when he dropped the baby in scalding hot bathwater before his death, she didn’t seek medical help for the boy. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Other states’ laws arose in different circumstances and at different times, but many came as part of a general trend, starting in the 1960s, toward stricter child abuse statutes.

Domestic violence advocates began to organize on a national scale in the late 1970s. When lawmakers in Minnesota and Iowa created failure-to-protect laws in the mid-1980s, they added specific defenses for parents who reasonably feared they would be harmed if they stepped in to stop child abuse.

In the early ‘90s, Texas also added such a defense to its omission statute, but it was a narrow one. It would not apply if the parent were aware of any child abuse prior to the incident in question — a sharp contrast to Iowa, which extends its defense to parents aware of “continuing abuse.”

Even as understanding of domestic violence grew, and as prosecutors built up a track record of using omission laws, some legislators still didn’t envision battered women being prosecuted under such laws. In 2000, Oklahoma state Rep. Jari Askins authored a bill that created the crime of “enabling child abuse,” with the word “enabling” meant to drive home that a failure to act was enough to warrant prosecution.

In an interview, Askins said that she has paid keen attention to domestic abuse against women throughout her career, going back to when she was a judge in the 1980s, when there was no specific crime for assaulting a spouse or partner. As a legislator, she helped pass a law stiffening penalties for committing a domestic assault in front of children.

But during the creation of the “enabling child abuse” law, the prospect that it might help imprison battered women wasn’t on the radar, Askins said. “We weren’t thinking about domestic violence.”

Askins said she is sympathetic to mothers in those situations, and she thinks it’s an important mitigating circumstance. But she doesn’t think protections need to be built into the law. She made a point that White, Lindley’s prosecutor, also made: Defense lawyers can raise that sort of evidence in court, and judges and juries can consider it as they weigh guilt or innocence and decide on punishment.

But often, it’s prosecutors who deploy the fact that the woman was battered. Some point to failed attempts to leave the abusive partner as proof that the mother wasn’t completely helpless and could have done more to save her child. Others cite contact with police or social service workers about domestic violence prior to the child's injury as missed opportunities to disclose more about the danger posed to the child. Many, in one way or another, present the man's violence as a testament to the mother’s poor decision-making.

In his opening statement in the trial of an Oklahoma mother accused of enabling child abuse, the prosecutor told the court that the man had also abused the mother. But, the prosecutor said, “She made the decision to stay.” He added, “It's about putting your child at risk because of the choices you make, and the choices you make to stay in an abusive relationship.”

Whatever Askins and her fellow lawmakers intended, Oklahoma prosecutors have used the law vigorously. Of the states BuzzFeed News examined, Oklahoma had the most women imprisoned for a decade or more: 20 overall, including four cases in which BuzzFeed News found evidence that the imprisoned mother had been battered. In Ohio, with three times the population, BuzzFeed News found a total of just three cases.

In fact, the likelihood that a woman will get a severe sentence depends largely on where she lives. In Minnesota the maximum sentence for permitting child abuse is one year. In Oklahoma the sentence can be life. And then, even within a state, it is individual prosecutors who decide whether to press charges and how aggressively to do so.

In one of the only cases that ever captured the national spotlight, prosecutors actually changed their minds. Twenty-seven years ago, 6-year-old Lisa Steinberg was found comatose with brutal injuries in a fetid Manhattan apartment. Her mother, a 45-year-old children’s book author named Hedda Nussbaum, initially faced murder charges alongside her husband, attorney Joel Steinberg, who would eventually be found guilty of manslaughter.

But it quickly emerged that Steinberg had battered both wife and daughter: At the time of her arrest, Nussbaum had a broken nose, fractured ribs, and a potentially life-threatening ulcer. Prosecutors dropped the murder charge against her. But whether Nussbaum deserved to go to prison became the subject of fierce national debate in the press — especially after she admitted at Steinberg’s trial that both of them used cocaine heavily, and that she had an 11-hour window between Lisa’s final beating and her death yet did not call the police. In the end, prosecutors did not charge her with “endangering the welfare of a child,” a misdemeanor in New York with a maximum penalty of one year in prison.

In Oklahoma, “enabling child abuse” carries the same sentence as actually committing it. Askins told BuzzFeed News that when her law passed, her only focus was protecting society’s most defenseless. Many issues have shades of gray, she said, but child abuse is not one of them. “I’ll protect the child at all costs.”

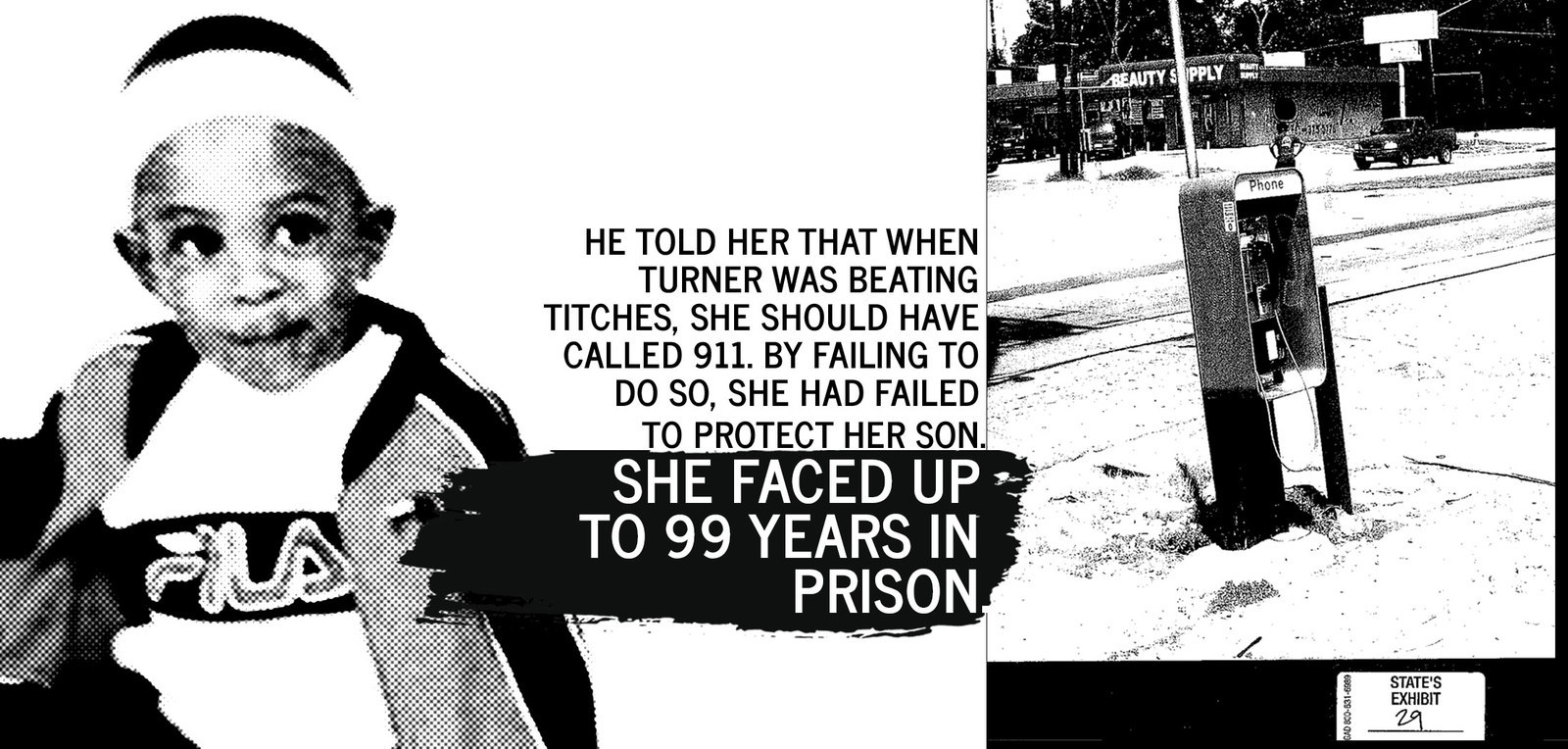

With the door slammed shut and Titches trapped inside with Turner, Chance and Lindley drove off to find a pay phone. Chance wanted Lindley to call 911. But Lindley worried that might set Turner off further, putting Titches in more danger.

“She was so scared of him,” Chance said.

Lindley later testified that her top priority was to calm her boyfriend down. Then with the situation under control, she and Titches could escape when he left for work. So instead of calling 911, Lindley called Turner, eventually negotiating a return to the apartment a few hours later.

What Lindley and Chance did not know is that while they were gone, Turner had more in store for Titches. The apartment manager, who had seen Lindley and Chance leave, could still hear Turner yelling, so she peered through a window into the apartment. She saw Titches on the floor. Turner kicked him in the stomach, repeatedly.

By the time Lindley and Chance came back to the apartment, Turner seemed to have calmed down, somewhat. Titches was dressed in fresh clothes, with a Band-Aid on his temple. Turner had bought some Pepto-Bismol, saying Titches’ stomach was hurting. But Turner began forcing the tired child to walk from the dining room table to the television, back and forth, again and again. Lindley begged him to let Titches lie down for a nap, and finally he relented.

He then ordered Lindley to go to the grocery store. Not wanting to reignite his fury, she agreed. Chance drove her; they stopped by a beauty supply store and a grocery store, and Chance dropped her back home.

Lindley put the shopping bags on the counter and checked on her son. His eyes were wide open, and he was turning back and forth on his bed, agitated. Then he stopped breathing.

When the paramedics arrived, Turner ordered Lindley not to ride in the ambulance with her son. Eventually, a police officer drove her to the hospital. Titches was dead.

A Dallas police detective walked Lindley, still crying, to an empty room and handed her a sheet of paper to write out what happened. Later, Lindley made a fuller statement to a different officer. The apartment manager gave her account too.

Turner was arrested that evening and charged with capital murder. The police report noted “no priors for family violence.” Prosecutors added a domestic assault charge, for hitting Lindley when she tried to stop him from beating Titches and for shoving her to the ground.

Lindley told BuzzFeed News that as she went about mourning her son, she had no inkling that she was a suspect herself. She had made both statements to the detectives voluntarily, and hadn’t been Mirandized. She continued cooperating with the police too, passing along Turner’s .22-caliber pistol, which she found in a shoebox as she cleaned out her apartment.

Five days after Titches’ death, one of the detectives who had taken Lindley’s statement appeared at her door with a warrant for her arrest. He told her that when Turner was beating Titches, she should have called 911. By not doing so, she had failed to protect her son. She faced up to life in prison.

Victoria Pedraza lied about the long green cord.

The cord puzzled Arkansas state trooper Clayton Moss, who was standing in the master bedroom. Lying on the floor, the long cord led up to a nearby closet rod, as if it were to be used as some sort of pulley.

It was February 2012, and a 2-year-old girl named Aubriana Coke had died, her body bruised so badly that, en route to the hospital, an EMT worker had called ahead to warn that it seemed like a child abuse case. Yet Victoria and her husband Daniel Pedraza, the child’s stepfather, claimed she had fallen off a fishing dock into rocky shallows.

Moss asked Victoria what the green cord was for. She grabbed onto the cord and pulled it back and forth, saying she used it to exercise. Victoria left, and Daniel entered the room. He said he used the cord to make bracelets.

Soon enough, the coroner showed there was no way the little girl had merely fallen off a dock — the internal injuries were too numerous and too traumatic, and scar tissue indicated ongoing abuse. At the end of the girl’s wake, police came in and arrested Victoria and Daniel, both on murder charges.

But as jail officials booked Victoria in, they discovered bruises all over her buttocks and legs. The next morning, she sobbed as she finally began to come clean. She would testify that Daniel had used the green cord amid 72 hours of extraordinary cruelty to her daughter, and to herself.

It’s not uncommon in these cases for battered mothers to lie and to take other actions that make them look guilty. Cases that BuzzFeed News reviewed featured one mother who left a battered women’s shelter — with her three children — to return to her violent boyfriend; some who left their children in the hands of their abusers when they went to work; and many who did not take their children to the hospital or call the police in the hours after a vicious attack.

In the eyes of many prosecutors, such actions enable child abuse and are clearly criminal. But many domestic violence researchers and advocates see the same behavior as evidence of just how victimized the women have become. The women’s decisions, they say, follow the logic of fear: Battered mothers are trying to manage the rage of their partners and avoid a more severe attack. “Anytime I interfered,” Victoria would later tell the court, “it would just make the situation worse.”

What’s more, victims of domestic violence often suffer ongoing trauma, meaning that the brain does not have time to recover the way it does from a one-off traumatic event, said Amy Bonomi, chair of the Human Development and Family Studies Department at Michigan State University. She was the lead author of a 2009 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine that compared women who had been victims of partner violence within the past year with women who had never suffered domestic abuse. Victims were more than three times as likely to have depression and almost six times as likely to abuse drugs or alcohol.

Victoria Pedraza eventually testified that the green cord was used neither for exercise nor to make bracelets. Three nights before Aubriana died, Daniel decided she should not be allowed to sleep and ordered her to stay standing up through the night. He awoke to find the little girl sitting down, so he tied the green cord around her waist, draped it around the closet rod, and attached it to his wrist. If she sat down again, the tug on his arm would wake him up.

He ended up beating both of them with a belt and his fists, hitting the little girl in the stomach so hard that it caused her internal organs to rupture. When Aubriana took her last breath, Victoria began CPR and begged Daniel to call 911. “And tell them what, Vicky?” she remembered him saying. Daniel went into the kitchen and returned with a knife, warning her, “If that little bitch dies, I might as well kill you too.”

“Kill me later,” Victoria said she replied. “Just help me — please.”

Finally, he relented. But before the ambulance arrived, she came up with a story that satisfied him: They would tell the authorities that the girl fell from the fishing dock.

After Victoria first confessed, prosecutor Thomas Deen worried that Daniel might try to exert influence on her from within jail, so Deen moved him to another county as he built his case. Deen concluded that Victoria had not abused her daughter. He agreed to drop the capital murder charge, as long as Victoria testified truthfully against Daniel — and if she pled guilty to “permitting child abuse,” a felony in Arkansas that warrants between five and twenty years in prison.

Daniel also pled guilty, in his case to first-degree murder. (In a jailhouse interview, Daniel told BuzzFeed News that despite his guilty plea, he was innocent of murder and that he never abused Victoria.) At his sentencing hearing, Victoria’s testimony helped put Daniel away on a life sentence. At her own sentencing hearing, she took the stand and told essentially the same story. But this time Deen’s prosecuting team cross-examined her.

On the evening of the fatal abuse, Victoria had gone to Walmart after Daniel had already punched her daughter in the stomach at least twice. Deen’s deputy asked why she didn’t get the police involved then.

“I was scared to death of Daniel,” Victoria answered. “I felt that if I interfered in a way, like, to call law enforcement, it would make things worse. Of course he probably would have went to jail. He probably would have got bonded out and he was coming right back. That’s the fear I had.”

“What about Aubriana’s safety?” the prosecutor asked.

“I feared that, too, yes.”

In his closing argument, Deen’s deputy pinned her on her early lies to the police. Victoria had said she didn’t begin to open up until she was in jail because that was the first time she didn’t have to fear how Daniel might react. The prosecutor disagreed. “It wasn’t that she felt safe,” he said. “It was that she was caught.” In rebuttal, Victoria’s attorney asked for mercy, brandishing pictures of the bruises jail officials found on Victoria when they booked her.

Victoria’s jury took less time to deliberate than Daniel’s had. Victoria got the maximum, 20 years. She will also have to register as a sex offender, even though her daughter suffered no sexual abuse. Under Arkansas law, that’s a requirement of anyone convicted of “permitting child abuse,” regardless of the type of abuse. (Victoria is appealing her sentence and her status as a sex offender.)

In his Main Street office this past spring, Deen said he had come to the conclusion that Daniel dominated Victoria’s every move — but that did not exonerate her. Victoria could have sought help from the police, or her family and friends.

She also had another option, one that Deen said he would not have prosecuted her for: “She should’ve cut his throat while he slept.”

Much of the case against Arlena Lindley centered on the fact that she did not call 911 in the hours after Turner beat Titches and threw her out of the apartment. The failure to make that call, police and prosecutors said, was a key part of her crime of omission.

But somebody else called 911, a fact that was not mentioned during Lindley’s case in court.

After the apartment manager had peered through the window and seen Turner kicking Titches, she had a colleague call the police. The call came in at 10:53 a.m. — around the time when Lindley and Chance would have been trying to figure out what to do.

An officer was sent to the scene. He entered the apartment and found no one. An upstairs neighbor said that Turner had taken the toddler and fled. Whether the officer or anyone else at the Dallas Police Department did anything in the ensuing hours is unclear. The police report, obtained through a Public Information Act request, classifies the incident as “miscellaneous” — not as the more urgent “offense,” which warrants an immediate criminal investigation.

“Please route to CPS,” the report says, referring to Child Protective Services. It notes that the location and condition of the victim is unknown, and does not indicate any further attempt to track down Turner or Titches. Dallas police declined to comment on the case. The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services declined to comment on whether it received a report from the police and on whether it took any action that day, and it rejected a public records request for documents on Titches' death.

Paul Johnson, Lindley’s court-appointed attorney, didn’t respond to a written question asking why he didn’t raise the 911 call in court. In an earlier interview, he had said that he couldn’t recall the specifics of Lindley’s case and that he no longer had access to any of the case documents.

Police were called again at 2:13 p.m., according to the next report provided through the public records request. By then, Titches had stopped breathing.

The day of Titches’ death was not the first time police responded to a call about his welfare. A few months earlier, a relative alerted authorities after she noticed bruises on his back. A detective visited the apartment and found Turner, who said that neither Lindley nor her son were home. Turner told the officer that Lindley’s family had been making false claims about the child.

Titches’ father, William Wade, had also caught wind that something was going on. He would later testify that he also called Child Protective Services, and that he was told a caseworker had checked on Titches and found nothing wrong. He also called the police, he told the court, but had no luck there either.

Around that time, Wade called Lindley himself and asked her directly whether Titches was getting hurt and if he could come and check on their son, to make sure. Wade could hear a lot of commotion in the background, he testified. It sounded like a male voice “hollering and screaming.” Then came what sounded like tussling. Then the line went dead. Turner, it seemed, had snatched away the phone.

Wade did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

(Wade’s mother, Cathy Lee, has created a foundation in Titches’ name. State and federal records indicate the foundation is not registered as tax-exempt. Lee declined requests for an interview.)

Though Wade is Titches’ father and harbored suspicions that his son was being abused, he has not been charged with a crime. The reason, prosecutor White told BuzzFeed News, is that he did not know for sure that Titches was being abused, and did not witness the abuse on the day the boy died.

Chance also was not charged with the omission crime — and couldn’t be because she wasn’t Titches’ parent or caregiver.

Unable to afford bond, Lindley stayed in jail for 15 months as she awaited the resolution of her case. She was willing to testify against Turner, but that wasn’t necessary — he pled guilty to murder in exchange for a life sentence with the possibility of parole.

Prosecutors offered a plea deal to Lindley, too: 10 years in prison.

Johnson, Lindley’s attorney, decided he could do better, though not by winning her an acquittal. He decided on an “open plea,” where she would admit guilt on the omission charge and make her case for mercy in court. She had powerful points in her favor: Titches’ father and paternal grandmother were willing to testify in her defense, despite the fact that Lindley’s relationship with Turner had led to the boy’s death. In fact, Lindley told BuzzFeed News, Johnson seemed confident that he could get her probation.

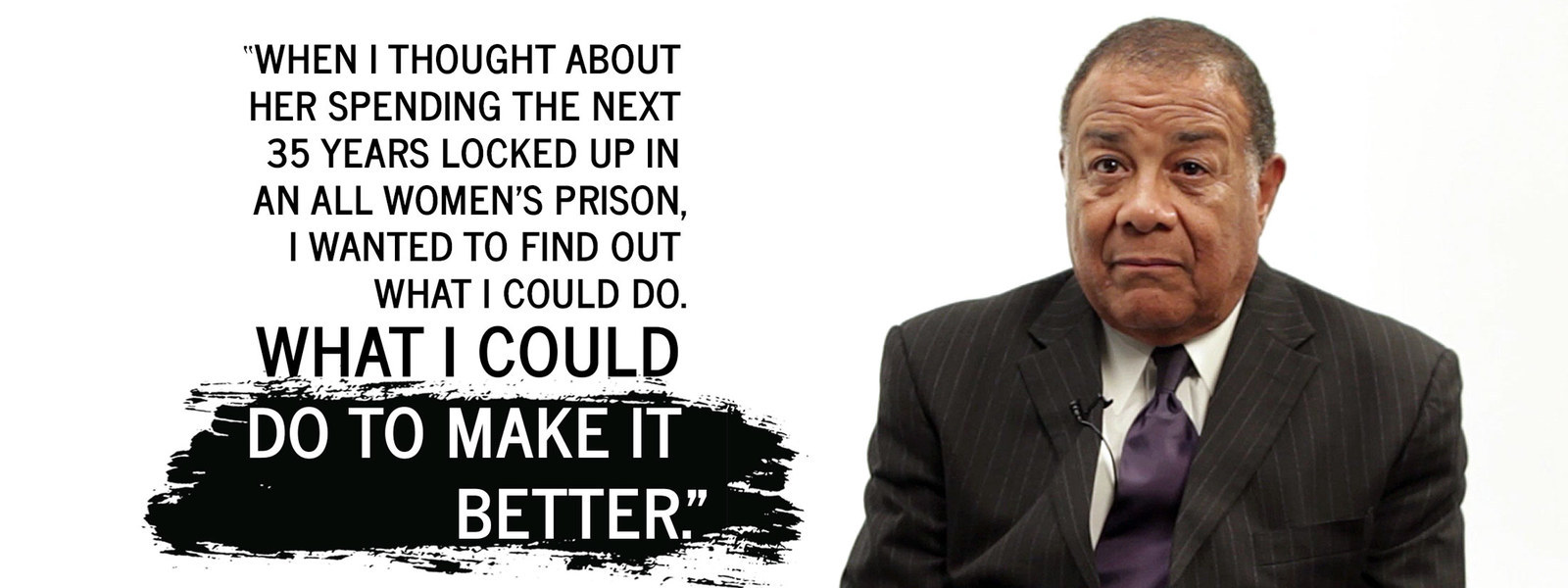

“You know, this case has haunted me,” Judge Kenneth Watson said in open court this March. Before him, in prison-standard jumpsuit, was a 24-year-old woman named Victoria Phanthtaranth. Just a year earlier, Watson, a state judge in Oklahoma City, had sentenced her to 35 years in prison.

Now Watson was reconsidering her plight. In three and a half decades of practicing law, he said from the bench, “I’ve never had a case that has stuck with me the way this has stuck with me.”

After Phanthtaranth's 3-year-old daughter Alexis died from a massive skull fracture, investigators determined that Alexis’ stepfather Freddy Mendez had caused the fatal injuries. But there seemed to be little doubt that, at the very least, Phanthtaranth did little to stop him.

“Everybody just thought that she was complicit,” Watson told BuzzFeed News. In a plea deal, she pled guilty to “murder by permitting child abuse.”

Then Mendez’s murder case went to trial, and Phanthtaranth testified for two days, under no promise of a lighter sentence. Mendez was convicted, but after the trial Watson’s court reporter talked to jurors about Phanthtaranth’s testimony. “Most of the women on the jury were just in tears about what had happened,” Watson said.

Mendez’s killing of little Alexis was brutal — he picked her up and slammed her into the ground — but so was his treatment of Phanthtaranth. One way he liked to get her attention, she told the court, was to grab her by the throat. A few weeks before he killed the girl, Mendez threw Phanthtaranth in his family’s swimming pool, then he continued hitting her in the bedroom, pushing her into the closet. When he was done, he demanded that she make him a sandwich. He called her his maid and his slave.

Though Phanthtaranth had enlisted a friend to get out of a previous abusive relationship, she didn’t tell the friend much about this one, because, she testified, she was “ashamed and embarrassed.”

Prosecutors agreed to allow for a new hearing, in which Watson would decide whether to alter her sentence.

Phanthtaranth’s ankle chains clinked as she ambled up to the witness stand. She was asked to raise her voice so everyone could hear her. Prosecutor Gayland Gieger asked what she would go back and change. “You know how many times I’ve thought about that?” she said.

She said she wondered whether she should have just killed Mendez — “forgive me for saying that,” she told the court — or found some other way to get away from him. Her mind often wandered to the simple fact that she was holding her son as she watched her infant daughter suffer the fatal injuries. “Does it mean that I chose my son over my daughter?” she asked.

With both sides finished, Watson said he would impose a strict probation plan and suspend the remainder of Phanthtaranth’s sentence. She is now free and works as a cashier.

Watson told BuzzFeed News that he thought about how Phanthtaranth had suffered from repeated physical and sexual abuse growing up in foster homes. And she had already been behind bars more than two years for Alexis’ death. “How much is one person expected to endure?” he said.

What troubles Watson is something he acknowledged both in the sentencing hearing and in an interview. Had Mendez just pled guilty, instead of taking his case to trial, he probably never would have learned of the abuse Mendez meted out on Phanthtaranth. “They both would be in right now,” he said, “and nobody would have even had a second guess about it.”

On Jan. 17, 2008, Judge Jeanine Howard called Arlena Lindley’s sentencing hearing into session.

White, the prosecutor, made her case first: After hearing from the medical examiner and two police officers, she called Lindley’s friend Chance to the stand. Chance confirmed that Lindley didn’t call 911 but instead called Turner. She also said that Lindley could have brought Titches to her father’s home to keep him safe.

On cross-examination, Lindley’s attorney, Johnson, asked Chance, “Did you ever think that Alonzo was going to kill Titches that day?”

“No,” Chance replied. Lindley, she also testified, was a good mother to Titches.

“How was Arlena, around Alonzo?” Johnson asked.

“She was, like, scared of him.”

“Constantly?”

“Yes.”

Next, White called Anthony Love, Chance’s cousin, who testified that he saw Lindley after she and Chance were thrown out of the apartment and that he did not like the way Lindley was reacting to Turner’s abuse. “When I asked her, ‘You don’t — you see this boy doing this to your child and you don’t want to call the police or nothing?’ She just gave me a smirk,” he said. “And I got upset and asked my cousin to remove her from my premises. I did all that I can do.”

The defense called Titches’ grandmother, Lee. She told the court that Lindley "has my love and support" and added, “I think that our family has really suffered enough. We lost Titches. I don’t want to lose her.”

Titches’ father, Wade, testified that he thought Lindley “was a perfect mother. It would be unfair to my son, knowing that he [is] in a better place right now, to sit up and try to badger her and say that she was just a terrible mother toward my son.”

When Lindley herself took the stand, she said she thought she was “doing the right thing” in trying to wait out Turner’s rage. “I actually thought if I would do what he say,” she said, “he would calm down.”

Then Judge Howard turned to Lindley and asked her whether Titches was crying that morning, before she and Chance left the house. Lindley said yes.

“And you just sat there?” the judge asked.

“No,” Lindley replied. “I tried to help my son.”

“I’m sorry?”

“No, I tried. I didn’t sit there. I tried to make him stop.”

“What attempts did you make? What did you do?”

“I yelled at him so he would get the attention off Titches, and that’s when he came at me.”

“And what was Titches doing then?”

“He was crying.”

“And was he still crying when you left the house with Latricia?”

“I don’t remember… I was trying to get my son. I don’t remember. Because I had him. He snatched him back. I don’t remember.”

In closing arguments, Johnson reiterated his plea for mercy and said, “What I have got beside me is another victim of Alonzo Turner.”

White, the prosecutor, countered that the judge needed to make a statement that a mother should “step up” and at the very least call the police or paramedics. A mother, she said, is supposed to “lay her life, if she has to, on the line for her child.” She reminded the judge of the state’s plea deal offer of 10 years. “We believe that the court will make the appropriate decision,” White said, “on the amount of time she spends in prison.”

Then Judge Howard handed down the 45-year sentence. “Like the prosecutor said, this is the last justice for Titches,” she stated. “The evidence showed me you were more worried about yourself than your child on October 13th, 2006. You failed to protect him from that horrible beast you were living with. You had a duty to protect your son, and you let him down. You didn’t nurture him when he needed you the most.”

Years later, White recalled that she was “shocked” when Judge Howard went far beyond the 10-year sentence she had offered. Still, White said she feels that 45 years is plenty fair. Lindley, she said, watched Turner “torture” her only son, “and then she got in her car with her friend to get hair products.” White said, “She deserved what she got.”

White did not initially remember that her office had viewed Lindley as a victim, having charged Turner with assaulting her on the day he killed Titches. She acknowledged that many see child abuse and domestic violence as linked, and she said that in many of the cases she sees, the perpetrator has committed both. But, she said, she runs the child abuse division of the Dallas County Prosecutor’s Office, and a separate division handles domestic violence. “Why women stay, and that — I can’t speak to that; I have no expertise in that,” she said. Her division focuses on “only the children.”

White also did not recall that someone else called 911 when Lindley hadn’t, but White said that fact didn’t mitigate her sense of Lindley’s guilt. (Judge Howard declined to be interviewed and did not respond to a written question about the 911 call.) A call from a mother would have carried more weight than one from a neighbor, White said, and the fact that someone else phoned didn’t relieve Lindley of her duty as a mother to take action. “In the end,” White said, “she walked out alive, and he didn’t.”

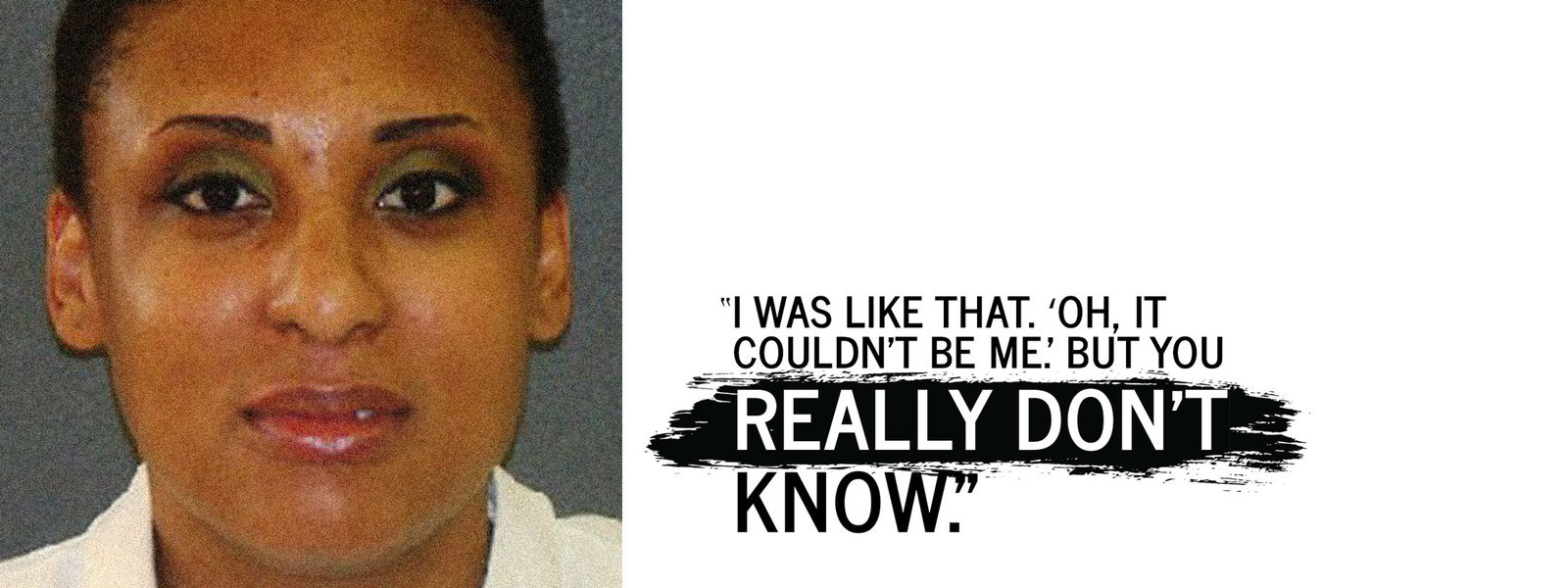

Lindley stays in an all-women’s prison off a stretch of farmland halfway between Austin and Dallas. She has been behind bars eight years. Having lost her first attempt at parole, she will have to wait until 2016 to try again. The parole board cited its “nature of offense” rule, reserved for prisoners whose acts were too egregious for them to be granted clemency.

Told that many people believe that in a situation like hers, they would do anything to protect their children from abuse, she said, “I was like that. ‘Oh, it couldn’t be me.’ But you really don’t know.”

Titches would be 11 years old now. He’s been dead for twice as long as he was alive, so Lindley’s memories are frozen in his baby years — learning shapes and colors on the internet, playing with his Hokey Pokey Elmo. Titches' name is tattooed on the inside of her wrist.

Anita Badejo, Jeremy Singer-Vine, Julia Furlan, Ellie Hall, and Nicolás Medina Mora contributed reporting to this story.

Audio of Victoria Pedraza's confession to the Arkansas state police.

Audio of Victoria Pedraza's confession to the Arkansas state police. Judge Kenneth Watson discusses Victoria Phanthtaranth's case with BuzzFeed News.

Judge Kenneth Watson discusses Victoria Phanthtaranth's case with BuzzFeed News.