This is part of a BuzzFeed News Investigation. Other main stories in the series include:

Detective Guevara's Witnesses and related video

Roberto Almodovar Finally Walks Free

Justice Delayed

The Night Shift

Roberto Almodovar held his head high when he walked free after 23 years in prison. He kept it that way when he was embraced by five other men who say they, too, were framed for murder, all by the same cop. It was the dress that finally made him break down.

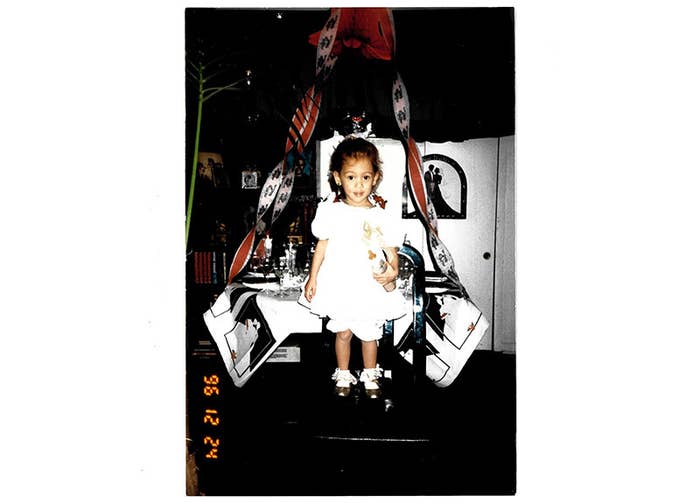

Days after his release, after he had returned to his room in his aunt Mary’s house, after the TV news trucks and the waves of visitors had all receded and he was beginning the work of putting a post-prison life together, he found a photo of Jasmyn — the daughter who had been just an infant when he was arrested, who he had spent those long decades yearning for, who was now a young woman sitting beside him on the couch, scrolling through her phone. She was 2 years old in the photo, wearing a shiny party dress.

“I still have that dress,” his aunt said, fishing around in the closet until she found it.

He ran his fingers along its gold neckline and its tiny gold bow. Suddenly he could feel it: all that he had lost, all her firsts, all the people who had picked her up from school because he wasn’t there.

He hung his head and wept.

On the night of Aug. 31, 1994, Almodovar had just finished the GED class he was taking and come home to his aunt’s house when he and his girlfriend started to fight. It was a bad one: They fought so loudly, so long, and so late that it woke a neighbor next door. It even drowned out the sound of nearby gunfire.

That gunfire killed two people who had been sitting on a stoop around the corner.

Two witnesses to the shooting picked Almodovar out of a lineup. One of them later testified that the lead detective pressured him. There was no other evidence against Almodovar. Still, despite his alibi, despite the neighbor who heard him in his aunt’s house during the shooting, he was charged with two murders. A jury convicted him and sentenced him to life without the possibility of parole.

His aunt Mary Rodriguez, along with her sisters Gladys Ramirez and Iris Mojica, fought for the next 23 years to exonerate their nephew, spending long nights at the dining room table mapping the cracks in the case, and mortgaging a family home to pay for legal fees. Eventually, with other families in the neighborhood, the aunts helped uncover dozens of cases in which Reynaldo Guevara, the lead detective in Almodovar’s case, was accused of misconduct. More than 50 other people say he framed them, too.

Last April, 10 days after BuzzFeed News published an investigation detailing the allegations against Guevara, prosecutors dropped the charges against Almodovar on the eve of his final appeal. He walked through the gates of the Cook County Jail a free man. His daughter, Jasmyn, sprinted past the jail guards to embrace her father.

As camera crews swarmed the dozens of friends and family members greeting Almodovar, five men stood patiently underneath a shade tree to the east of the throngs, waiting to welcome the newest member to the club to which none of them ever wanted to belong: men who Guevara had helped send to prison, and who were later exonerated. Combined, they’d spent more than 100 years locked away for murders they didn’t commit.

As Almodovar, a mix of smiles and tears, made his way over to them, they each recognized his expression. They’d had the same moment, felt the same joy. But they knew that walking out of prison isn’t the same as being free.

Depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anger bind these men in invisible ways to each other and to their pasts. They have struggled financially, professionally, and personally as they try to reclaim their lives on the outside. Guevara casts a longer and darker shadow than any of them could have ever imagined.

For Angel “Javy” Rodriguez, one of the first of the Guevara exonerees, freed in 2000 after nearly four years in prison, there’s the murder charge that he says keeps popping up on his background checks, even though he has since been declared innocent. Like most of the exonerees, he’s unable to explain away the long gap on his résumé, leaving him struggling from gig to gig.

For Juan Johnson, exoneration meant closed drapes, locked doors, and his grandson softly crawling up next to him in bed asking, “Papa, why are you always so sad?” After a federal jury found that Guevara told witnesses to pick Johnson out of a lineup, he won a $21 million award (later reduced to $16.4 million). But the money did little to help him adjust to regular life. Instead, it isolated him further, leaving him suspicious of others’ intentions and overtures.

Jacques Rivera was freed after a 12-year-old witness testified that Guevara had manipulated him into choosing Rivera in a lineup. Medical records showed that the victim, a man who supposedly named Rivera as his assailant, had actually been in a coma at the time. That was six years ago. Yet Rivera still lives in fear. To open his front door he has to turn his back to the wall and look back and forth several times — just in case an officer is following him. He keeps shoeboxes and Target bags full of receipts, in case he ever has to prove his whereabouts. “When the gas pump says ‘see clerk for receipt,’” he said, “I go in and see the clerk to get my receipt.”

“The only program I’ve got is my family. If it weren’t for them, I’d be fucked. I’d be a bum in the streets.”

For Jose Montanez, freed a year ago, exoneration meant being able to walk into Wrigley Field to watch his beloved Cubs. But so many people packed so tightly was too much for a guy who’d spent 23 years watching his back. He had a panic attack and had to leave.

For Armando Serrano, freed with Montanez, exoneration meant simply standing in the middle of a block, a grocery store, or his mother’s home “feeling like I’m not normal. Like something bad could happen to me in an instant,” he said. “I feel like I’m still in prison.”

People who serve out their sentences receive support services like job placement, housing assistance, and counseling. People who are exonerated rarely do. They get a check from the state, based on how many years they spent behind bars. Beyond that, they mostly have to figure it out for themselves.

“The only program I’ve got is my family,” said Almodovar. “If it weren’t for them, I’d be fucked. I’d be a bum in the streets.” He has yet to receive the nearly $200,000 payout he’s due under Illinois state law. His lawyer, Jennifer Bonjean, plans to bring a federal civil suit against the city for all that he suffered.

Mary converted a corner of her finished basement into a bedroom for Almodovar until he’s able to save for his own place. That helps. But even the most basic requirements of American life have proven harder than anticipated.

When he went to the motor vehicle division for an ID card, he had nothing more than his birth certificate and a copy of the April 15 edition of the Chicago Tribune with a front page story chronicling his release. The worker behind the desk told him he’d need more.

Got a utility bill, the worker asked? Nope.

Cable? Pay stub? Nothing.

With no ID card, Almodovar couldn’t apply for public assistance or perform dozens of other daily tasks. A state that controlled every moment of his life as a convicted man suddenly couldn’t confirm his identity as an innocent one. “It's hard," he said, "and it shouldn’t be like that."

Getting a job has been even harder. Exoneration doesn’t change the fact that he’s a 42-year-old with less than two years’ work history. And even prospective employers who acknowledge his innocence are likely to worry about the scars he still bears.

One of Almodovar’s friends — his Aunt Mary used the term in air quotes — heard Almodovar talk about reclaiming his life, maybe going back to school. The friend works as a recruiter for an online Christian college. Without Almodovar’s permission, the recruiter signed him up. Suddenly a man who had barely ever used email had a student log-in, a course in crisis counseling, and a $6,000 student loan.

Scowling as he read the course requirements, he found one he’s never even heard of. “E-book?” he muttered in disbelief.

“They know he’s naive to all of this,” Mary said. “So why are they doing that to him? You’re supposed to help him, not take advantage of him.”

Frustrated, he snapped the laptop shut. “I just don’t want to fail.”

Almodovar was always careful about his appearance. Before his arrest, his family used to tease him about his inability to pass a reflective surface without checking himself out. These days, though, it’s not just vanity. The perfect part of his hair or the slim fit of his sweaters can help hide the turmoil he feels inside.

So when he was invited to an event at a law school, he headed first to a discount clothing store to buy a new shirt and tie. But the fitting rooms had a faint smell of rubber that reminded him of the inmate processing center at the Stateville prison, where toilets were crusted with feces and rats roamed freely. He felt the anxiety setting in. “I gotta get out of here,” he said to himself, rushing for the exit.

Mary notices the pain in small, subtle moments. Like the times she’s talking to him and he simply stares, still trying to size up a room and evaluate a threat that’s no longer there.

In the middle of their conversations, sometimes Mary fights her own disbelief. “He’s home,” she reminds herself. “He’s actually home.” Other days, the reality strikes her in more unpleasant ways. She notices that her nephew, once unfailingly respectful, is now more abrupt. “In prison, you have to be more direct," he explains to her. "That way people don’t misunderstand you."

“But we’re not inmates,” she responds.

His daughter taught him to use a cell phone, but he mostly just gets her voicemail.

His aunt Gladys saw his stress at a recent party. She was in the back of the room, catching up with an old friend when Almodovar arrived. As he walked through the room of strangers, his anxiety rose with each new face he passed. “Why weren’t you at the door?” he demanded. Gladys, who’d taken overtime shifts at the her job at the candy factory and moved into her father’s unfinished basement to help save for her nephew’s appeals, bit back. “Lower your damn voice,” she told him. Weeks later, he still can’t make Gladys understand his anger in that moment. He’s sometimes still scared in a room full of strangers. Anxiety, panic overtake him. “I don’t know who is going to come at me a certain way.”

For the 23 years he was incarcerated, Almodovar did his best to shield his aunts from the horrors he saw behind bars. In quiet, unguarded moments when it’s just family, the truth now slowly seeps out. They hear for the first time a story about an inmate who gouged out his cellmate’s eyes during a fight. He tells them about another inmate who was just days from completing his sentence. He heard that the guards placed him with a man who’d vowed to kill any cellmate, just to see if he’d do it. According to the story, he did.

View this video on YouTube

Almodovar's release from prison after 23 years.

There have been happy times, too. He’s accepted invitations from friends and family to attend two Cubs playoff games, attended his first concert at Chicago’s famed Soldier Field, and made his first voyage on an airplane, to visit New York City on his first vacation.

“I try to face my fears and get past it,” he said. “It’s just enjoying life. I see a lot of people just rushing to do things. They don’t take time to just enjoy the little things.”

No matter how much he tries to catch up on the things he missed, 23 years are still gone.

Yet no matter how much he tries to catch up on the things he missed when he was locked up, 23 years of his life are still gone. And most painfully for Almodovar, so too are 23 years of his daughter’s.

On the day of Almodovar’s release, Jasmyn sat with him on the family couch as he ate his first meal. She talked about all the things they would do together. Hot dogs at Portillo’s. Him teaching her to ride a bike. Her teaching him to use a computer. Halloween, together, with him dressed as the Joker and her as Harley Quinn.

At a welcome-home party for Almodovar a month later, Jasmyn surprised her father by re-creating key moments in her life. She walked out in her high school prom dress so that they could have their first dance. Then she slipped into her graduation gown and swayed with him to the song “Daddy’s Home.” But when the reverie ended, Jasmyn was still 23, with her own life — job, friends, and dates that don’t include him. His aunt Mary tells him that he “has to fit into her schedule now.” Jasmyn taught him to use a cell phone, but he mostly just gets her voicemail.

At least once a month, the men who were exonerated after Guevara put them away for murder try to have dinner, go bowling, do something to strengthen their bond. If all else fails, they are certain to see one another at the court dates of other men who say Guevara framed them too.

Last month, several of the Guevara exonerees filled the gallery during a hearing for Jose Maysonet, who said he had been framed for a double murder. When Guevara, his supervisor, and other officers refused to testify about their investigation, prosecutors had to drop the charges and let Maysonet go after 27 years in prison. Almodovar headed down the courtroom steps to watch yet another man walk free from the gates where he had emerged seven months and one day earlier.

Almodovar recognized that same look, that mix of smiles and tears. As he watched Maysonet walk out, he knew some of the struggles he’d face, the adjustments he’d have to make. But he also knew the support Maysonet would have, if from no one else but the fellow members of the exonerees' club.

Eventually the time came for everyone to part. The sun had set and the air turned cold, so Almodovar zipped his jacket and turned his collar up. He walked with Aunt Mary back to her car, and headed home with her. He needed to finish sorting out the online course, and start working on his job applications. On the way there he thought of calling Jasmyn but decided not to. He didn’t want to bother her. ●