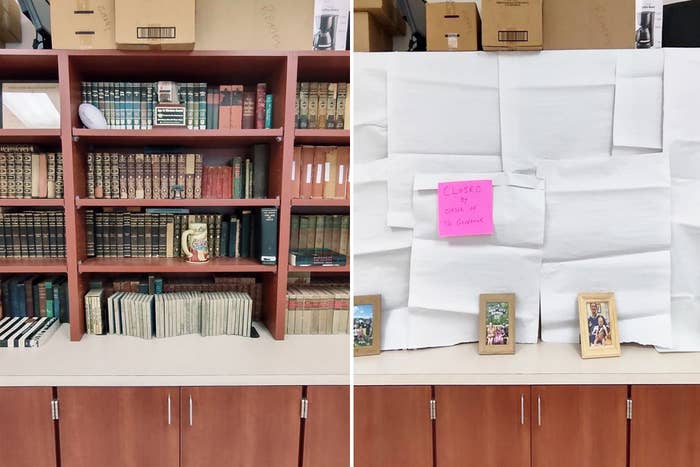

Surrounded by the full-to-the-brim bookshelves that line his Florida classroom walls, Don Falls struggled to make sense of the memo: Cover up your books, or remove them at once.

The directive sent to Manatee County School District teachers on Jan. 20 came in response to a new state law, which requires that all books go through a formal approval process with a certified school librarian or media specialist before being made available to Florida public school students. Any books already on the school’s approved list were permitted to remain in classrooms, but Falls, a history teacher at Manatee High School, had too many books to feasibly check them all. So, he covered his shelves, taping up large sheets of paper to conceal the contents.

“I have hundreds and hundreds of books,” Falls told BuzzFeed News. “I just really had no other choice other than to cover them up or remove them all, so I just covered them up.”

Though the law, HB 1467, went into effect in July 2022, it wasn’t until January that the Florida Department of Education published training on the new law, leaving many schools in limbo for months, uncertain how to proceed. HB 1467 allows parents, or even any resident of the county, to lodge objections to course material, and right-wing organizations are already taking advantage: One group, Moms For Liberty, has lobbied for more than 150 books to be removed from Florida school libraries, including The Color Purple, The Handmaid’s Tale, and many others that deal with race and LGBTQ issues. So far, most of those efforts have not been successful, but many schools are erring on the side of extreme caution when faced with angry parents.

Over the past two years, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has promoted a variety of staunchly conservative education laws. In June 2021, when “critical race theory” was becoming the right-wing panic du jour, he successfully spearheaded an effort to ban it from curricula, saying teachers were “teaching kids to hate their country.” Less than a year later, he rubber-stamped the so-called Don't Say Gay bill, which prohibits LGBTQ topics from being discussed in classrooms from kindergarten through third grade. Now, HB 1467 is the latest piece of the puzzle as conservatives work to reframe school policy in the state, with all the individual pieces of legislation coming together to create an environment of uncertainty.

“All three are very vague, and all three are interconnected,” Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association, told BuzzFeed News. “They're implementing them exactly how the governor wanted — he wanted chaos, he wanted confusion, he wanted books pulled out of schools.”

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, a spokesperson for Gov. DeSantis cited what the governor's office called inappropriate material in schools. "Our office has recently amplified several examples of inappropriate content found in Florida’s K-12 classrooms, which well exemplify the gender politics and sexualization agendas that ideologues are attempting to push via the public education system," Deputy Press Secretary Jeremy T. Redfern said. "The governor won’t let these agendas pervade Florida’s education system unanswered." The four books cited by Redfern were found in high school libraries, according to the Orlando Sentinel, and had already been removed from most of the schools before the DeSantis administration complained.

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Florida Department of Education communications director Alex Lanfranconi said, "If educators are confused about what can and cannot be taught in Florida schools, the blame lies solely on media activists and union clowns who purposefully sow confusion and mislead the public."

But many of the educators interviewed by BuzzFeed News said their confusion stems from the legislation itself, with the murkiness of HB 1467’s finer points only serving to exacerbate that. Though the law does not directly address penalties for unvetted books, the text cites Florida statute 847.012, which makes it a felony to distribute sexually obscene material to minors. “What they've essentially done here is say that books now are part of that, and that if you give books [to students] that someone deems is pornography, then you can be charged under that statute,” Spar said. Many books with LGBTQ themes have been targeted for removal, whether or not they actually include sexual content.

An award-winning book about the true story of a same-sex penguin couple raising a chick has been banned by a Florida school district in response to book banner @RonDeSantisFL’s don't say gay" law: https://t.co/8ni12YSFub

Communications from some school districts to their teachers underscored the risk of legal action. A January email from Manatee County Superintendent Cynthia Saunders, which was obtained by the Washington Post, said violating the book law could result in “a felony of the third degree.” Duval County Public Schools administrators also instructed faculty to cover or remove their classroom libraries, mentioning the felony risk in a video on how to comply with HB 1467.

Though most teachers don’t think they’re likely to face criminal charges, there remains the very real possibility of professional ramifications. A spokesperson from the Florida Department of Education suggested that noncompliance could be punished harshly, telling the Washington Post that disobeying HB 1467 could result in “penalties against” teachers’ teaching certificates. And since many Florida teachers are employed on annual contracts, rather than being tenured, school districts can simply opt not to rehire those teachers without cause.

“This year has been kind of like walking on eggshells,” said one Orlando-based middle school English teacher, who asked to remain anonymous due to safety concerns. On Friday, a far-right Twitter account — which is notorious for smearing teachers as “groomers,” targeting them for doxxing, and even bragging about getting teachers fired — posted TikToks the teacher had made parodying the book ban. As a result, he was placed on paid leave, with the school saying it was because students had appeared in the video. Since then, he’s been bombarded with harassment.

Already, the English teacher had found himself in hot water. Earlier this month, he showed his class two episodes of The Proud Family — one from the original series, and one from the Disney+ reboot — for a lesson on how representation in pop culture has shifted over the years. One student’s mother complained to school administrators, taking issue with the episode’s inclusion of LGBTQ and Muslim characters. Echoing recent conservative ire accusing the series of being “critical race theory,” the mother said she “didn't want her student to be exposed to ‘wokeness,’” he said.

Not wanting to escalate the matter — further angering the mother, or even possibly opening themselves up to a lawsuit — administrators called off the lesson, and the student was removed from his class.

“It's a slippery slope — let's say that student stayed in my class, I'm sure that parent would definitely want to see what books are on my library shelf,” the English teacher said. Though he doesn’t mind talking to parents about what their children are learning, he now realizes how easily these laws can be used to stifle lessons that don’t conform to certain worldviews.

Even before these laws came into play, teachers across the state were already struggling. On average, Florida public school teachers are the 48th lowest paid nationwide, according to data from the National Education Association. Like many states, Florida is also in the midst of a severe staff shortage, with the Florida Education Association estimating over 5,000 teacher vacancies in January (a claim the state’s Department of Education has called a “myth”).

Teachers aren’t the only ones affected. Students also stand to be put at a disadvantage by the new restrictions, educators say — especially those whose own identities are banned from classroom discussion. The English teacher was disheartened to realize how many of the books targeted for bans are ones on LGBTQ topics. “I have students that are LGBTQ-identifying, and these books represent them,” he said.

Also troubling many educators has been the Florida Department of Education’s Jan. 12 announcement it would block the teaching of a new Advanced Placement high school course on African American Studies, a curriculum Gov. DeSantis had decried as “indoctrination.”

Kristin Mitchell, an intensive reading teacher at an Orlando high school, said this could have tangible effects for her graduating students. Nearly half the student population at Mitchell’s school is Black, and many go on to study at historically Black colleges and universities, where an African American Studies course is often a general education requirement. By taking the AP course in high school, they can test out of it in college, and progress more quickly in their studies.

“There's an Asian history class, there's AP history, there’s AP European History,” Mitchell said. “So why can’t we teach AP African American Studies?”

DeSantis has framed the influx of legislation as his righteous crusade against what he calls the “far-left woke agenda.” Perhaps not so coincidentally, he is also believed to be considering a run for the presidency in 2024. “Those political aspirations seem to be guiding him more than anything else, and he's putting his political aspirations ahead of our own kids,” said Spar, the FEA president.

Don Falls, the Manatee High School teacher, has since been allowed to uncover his bookshelves — the unvetted books are still off-limits to students, but they’re allowed to remain in classrooms as long as they go untouched. “The optics were so awful in the national media, with teachers covering up bookshelves, that I think the school district and school board had to backstep a little bit,” he said.

But even with his books back on display, Falls can’t help but see parallels between what’s happening in classrooms across his state and many of the lessons he’s taught over the years.

“As a history teacher, I couldn't help but think of the historical connotations of different points in our own history,” Falls said. “Whether it be McCarthy era, or 1930s Germany, or other places where the government has tried to silence people or control what people think and learn by banning books or restricting access to knowledge.”

He thinks of all the students who, as teenagers often do, have asked him, Why do I need to know this? When will I ever use this stuff?

“This is the reason right here,” Falls said. “You learn from history, and you learn from the mistakes and successes of what people have done in the past, so that when these issues come back around — and they will come back around again — you can have some context for understanding how to deal with them.”