More than a year ago, BuzzFeed News received a remarkable collection of secret government documents. This huge trove had been assembled at the request of law enforcement agencies and congressional committees investigating the 2016 presidential election and other matters. The documents contained private banking information about public figures and senior government officials around the world — along with suspected criminals and organizations tied to terrorism.

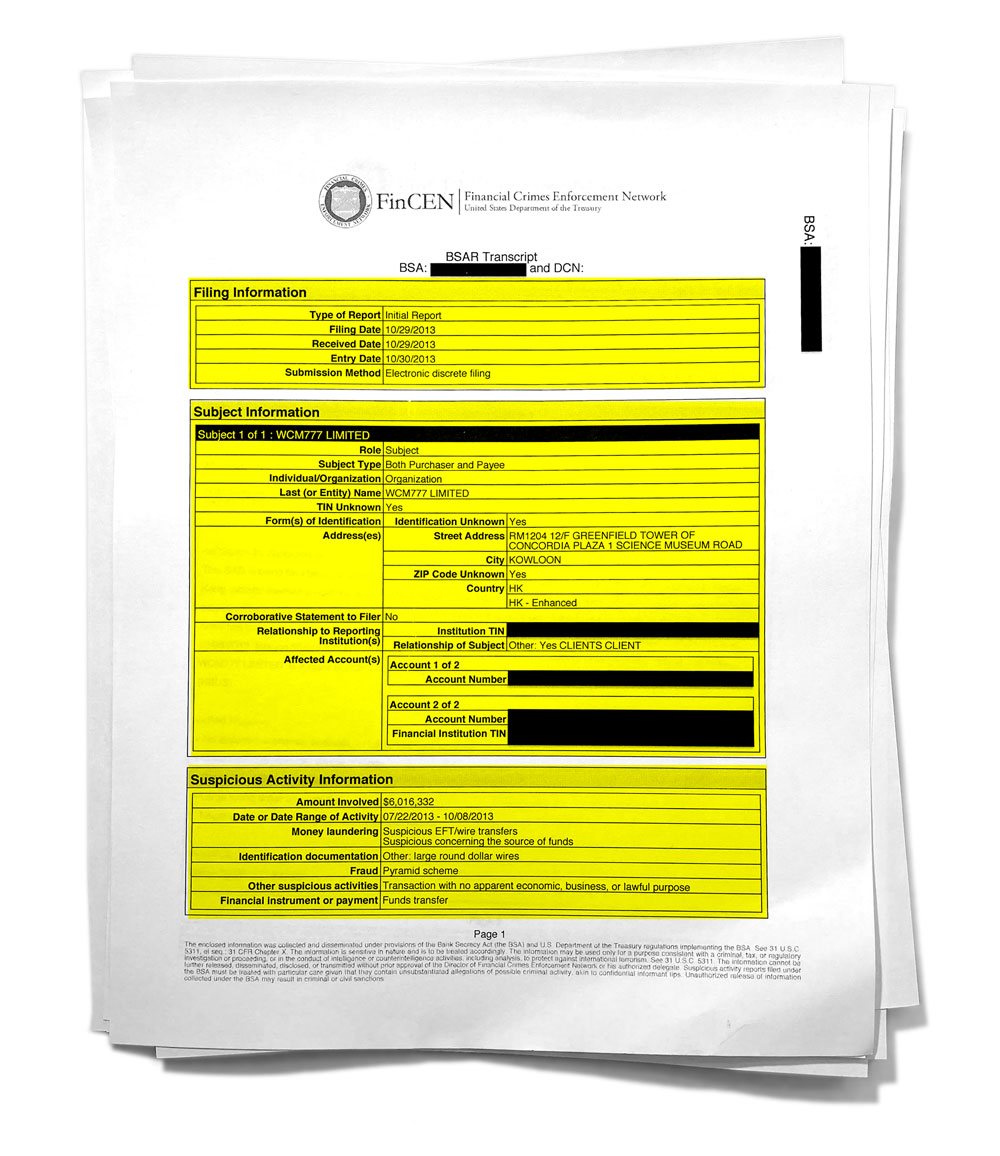

Among the documents were more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports, or SARs, which banks and other financial institutions submit to the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, when they observe transactions that suggest money laundering or other illegal activity. Such reports can support investigations and intelligence gathering — but by themselves they are not evidence of a crime.

These documents are so closely protected that they are never supposed to be available to the public. You can’t get them through Freedom of Information requests and you can’t subpoena them in legal proceedings. Banks are not supposed to admit the existence of a SAR — even to other banks. Prior to this reporting, very few SARs are known ever to have been revealed. BuzzFeed News has thousands.

Mostly dating from 2011 to 2017, although describing some transactions that occurred as early as 1999, the documents provide an unprecedented glimpse into global money laundering. To analyze them and crunch the numbers, BuzzFeed News teamed up with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and more than 100 partner news organizations from 88 countries.

What ensued was a yearlong data analysis collaboration that required thousands of hours of manual data entry, the creation of custom-built digital tools, machine learning, and specialized validation software.

But it all came down to those suspicious activity reports.

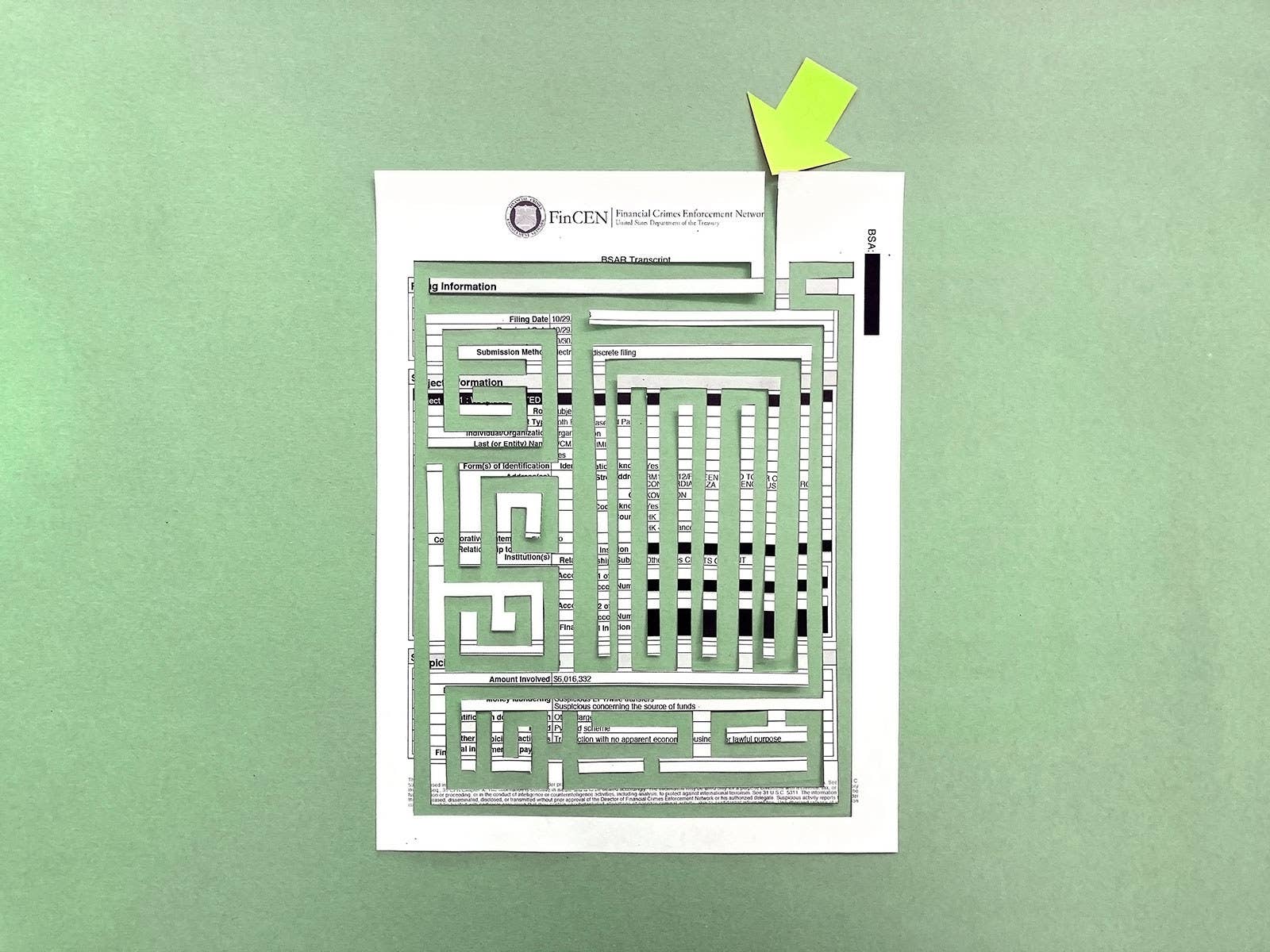

The Anatomy of a SAR — and How We Dissected Them

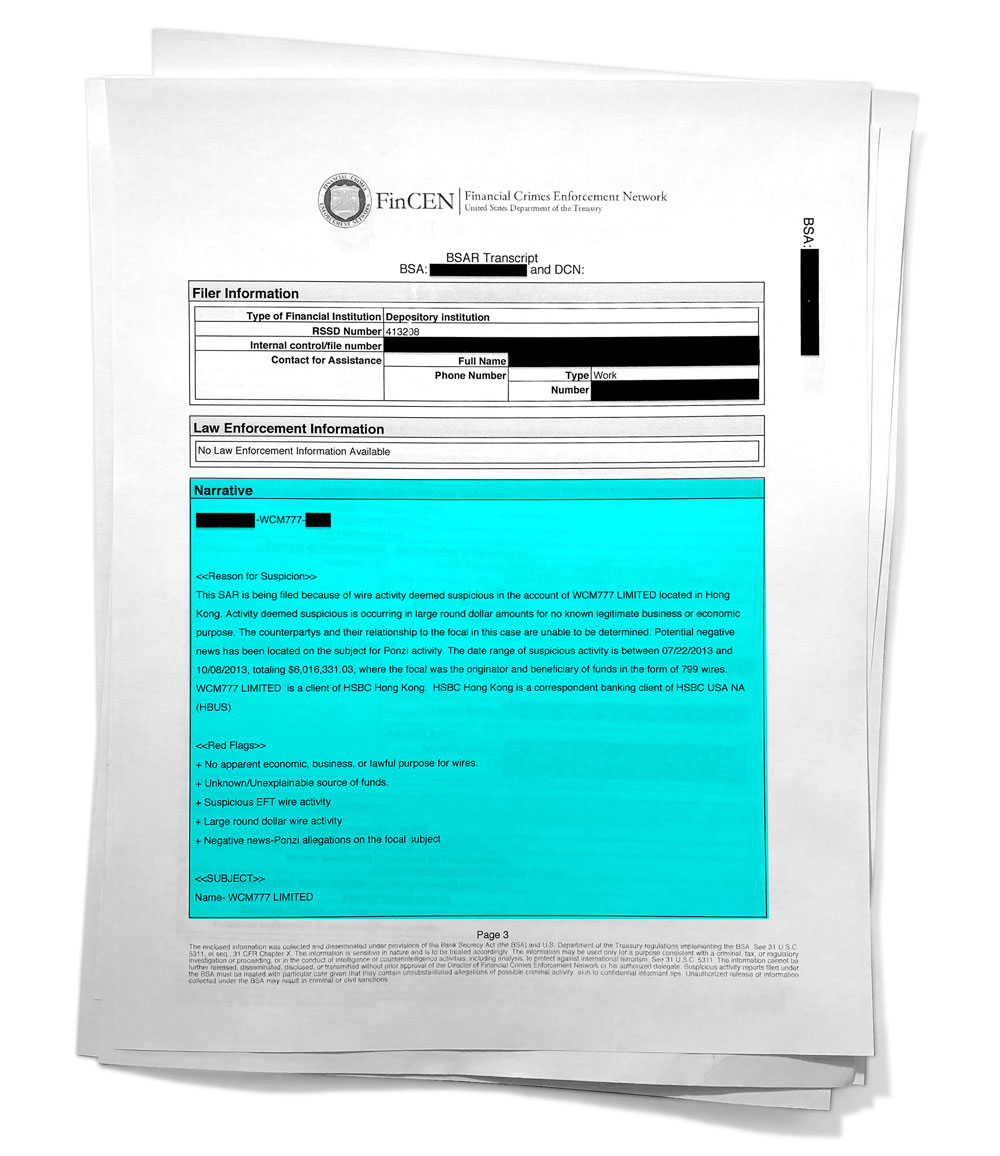

All SARs have two parts: a set of data tables and a narrative.

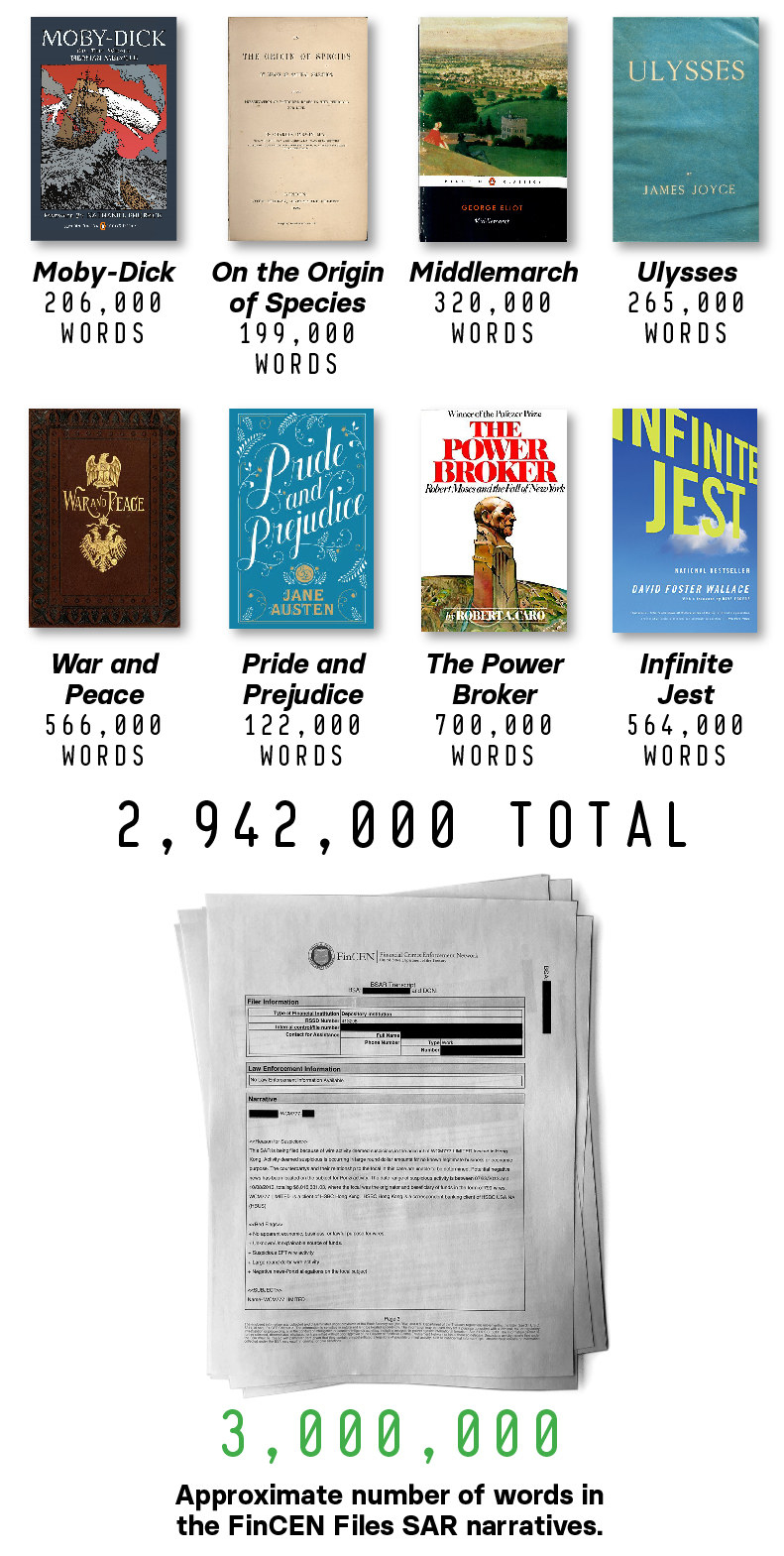

Some narratives are bare bones, while others are in-depth accounts including individual transactions, additional parties, and what the money was purportedly being used for. In the FinCEN Files, these narrative elements alone came to more than 8,000 pages — or about 3 million words.

We tried writing computer programs to automatically extract this crucial information, but we quickly discovered that it was not possible.

So with no other choice, we did it the old-fashioned way: We read every last page.

With the help of ICIJ’s document-collaboration platform, BuzzFeed News and the partner newsrooms divided the task among more than 80 reporters. For each document, the reporters captured every set of transactions mentioned. After that, ICIJ submitted each “extraction” to multiple rounds of validation. It was a massive effort, but it allowed us to map out more than 200,000 of the transactions in the SARs.

This effort gave reporters access to a greater level of structured, searchable detail than FinCEN itself provides to investigators.

In addition to the written SARs, BuzzFeed News received hundreds of spreadsheets that banks had sent to FinCEN. Although those files often lack the context of the written reports, they list more than 100,000 transactions.

But each bank has a slightly different way of producing these files. So ICIJ undertook an effort to standardize the field names and address formats to make them more useful to our partners.

More Than $2 Trillion — Yes, With a “T”

In total, these reports flagged more than $2 trillion in transactions. Here’s how it broke down.

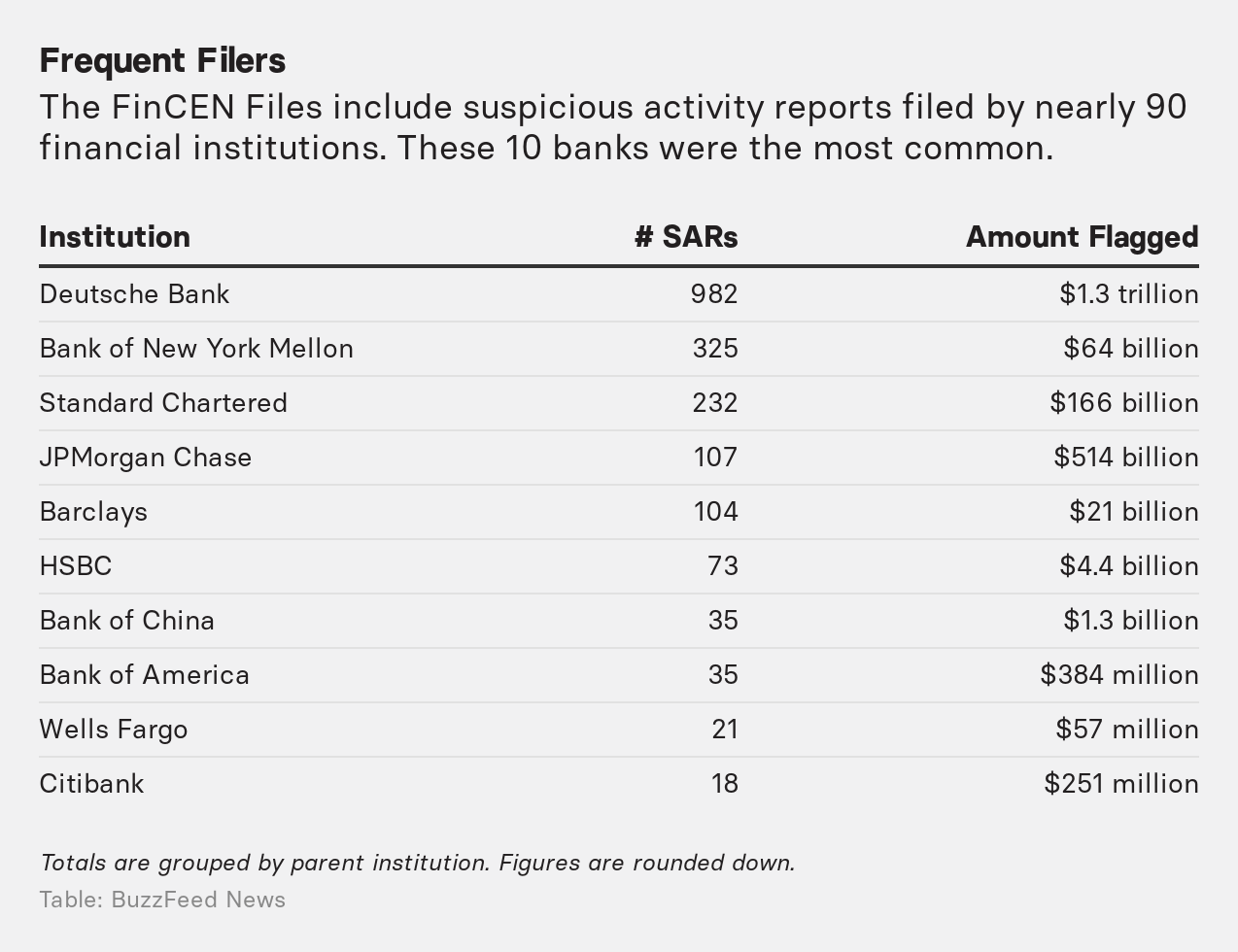

The Banks: The FinCEN Files contain reports submitted by nearly 90 banks and other financial institutions. This particular collection of documents is not a representative sample of what banks file overall. Within this subset, by far the greatest number of SARs come from Deutsche Bank.

Here are the top 10 banks represented in the FinCEN Files, plus the total value of suspicious transactions they flagged:

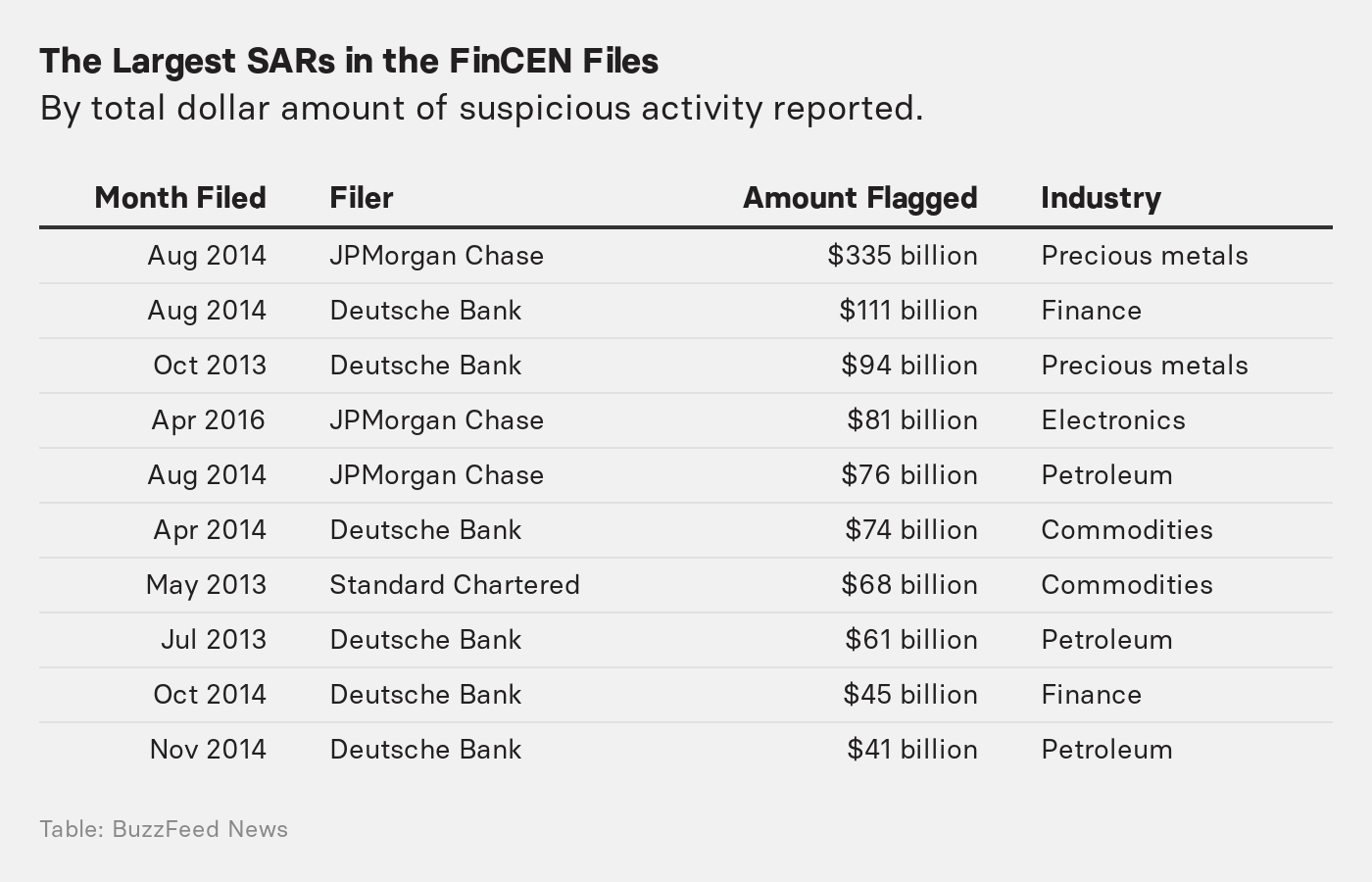

One report, filed in August 2014 by JPMorgan Chase, identifies more than $335 billion in suspicious activity, relating to more than 100,000 wire transfers “sent, received or processed” over the course of a decade-plus by MKS, a Switzerland-based company that trades precious metals.

“We cannot confirm your report of a purported SAR from a half decade ago of which we have no knowledge,” a spokesperson for MKS told BuzzFeed News and ICIJ. “We note, however, that referencing $335 billion in purported wire transactions over a twelve-year period creates a false and misleading impression about the scale and scope of our precious metal operations.”

MKS is “proud of our record of maintaining an industry-leading compliance program,” the spokesperson said, “and our long history of maintaining uninterrupted access to financial markets around the world.”

In total, 130 reports flagged at least $1 billion to the Treasury; these big-dollar reports account for more than 90% of all “suspicious activity” in these documents.

When banks first encounter suspicious transactions, they are supposed to file a report within 30 days. But that doesn’t mean all of the information is timely: SARs often refer to much older transactions, even some that occurred more than a decade before. This frequently happens when banks receive new information about old transactions or clients, such as when ICIJ published the Panama Papers; but other times, the reason is unclear.

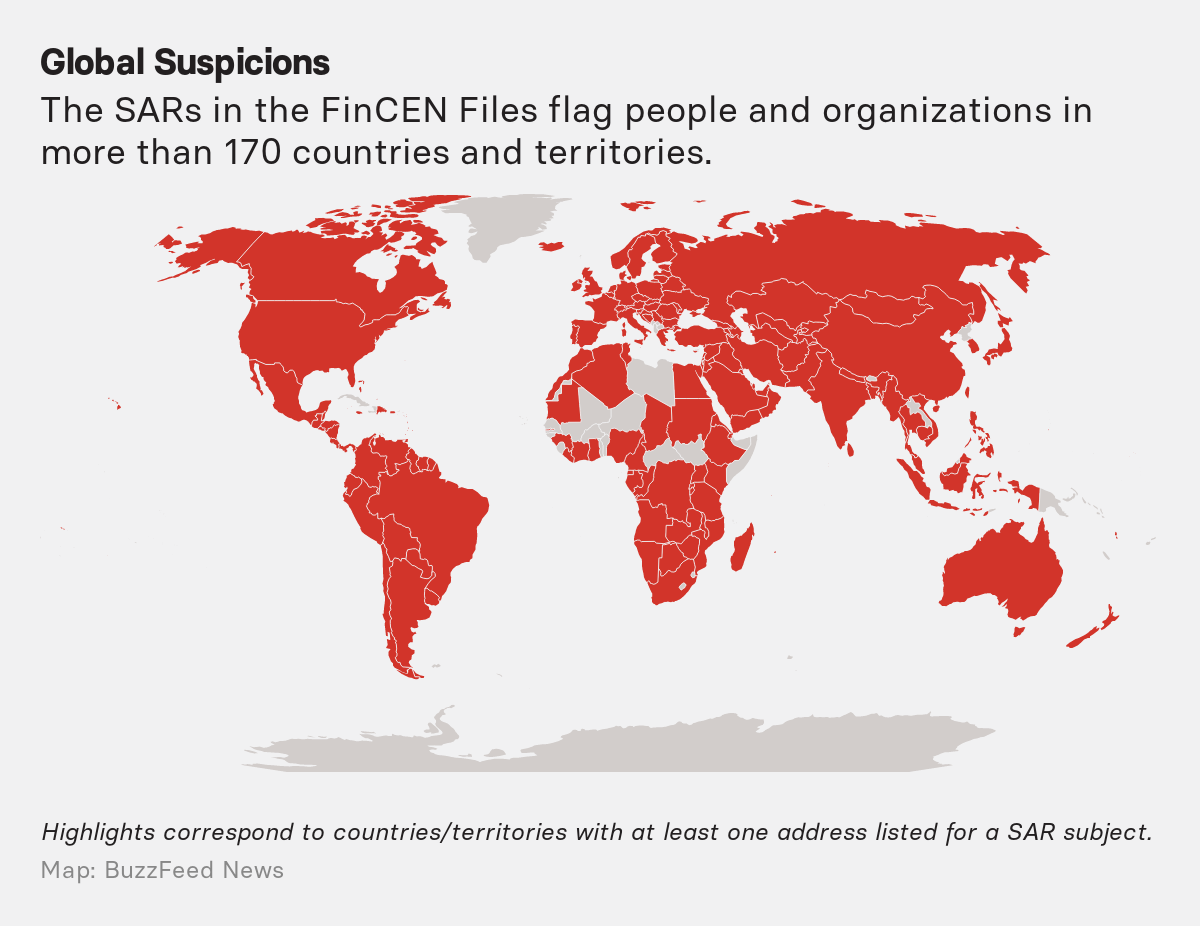

The Objects of Suspicion: The documents provide information on more than 10,000 people and organizations spanning more than 170 countries and territories. They also touch almost every state in the US.

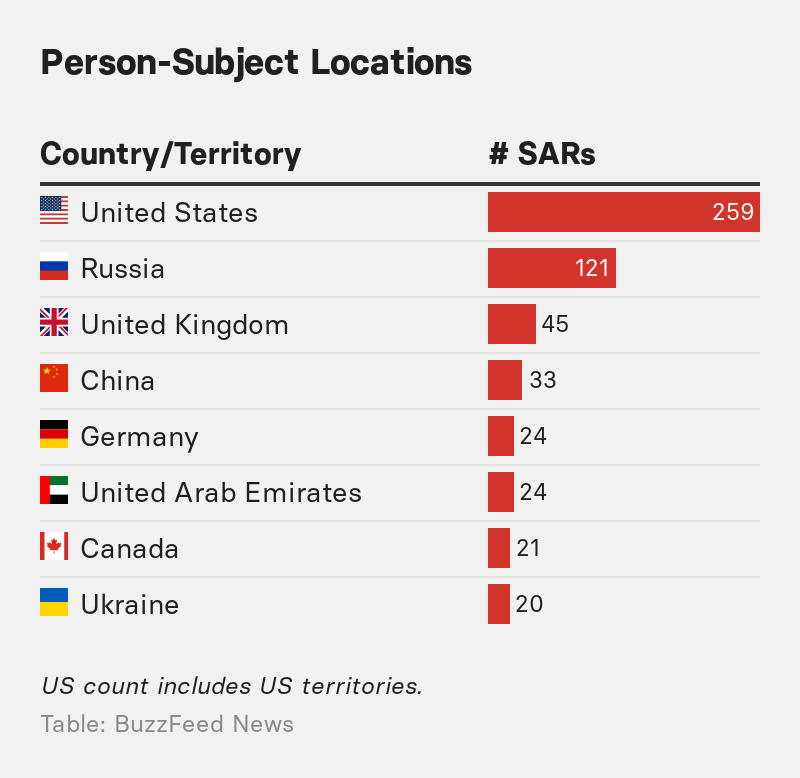

More than 250 SARs reference people with addresses in the US, and more than 120 with addresses in Russia. The UK, China, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, and Ukraine were also common locations for people, each appearing in at least 20 reports.

At least 25 of the people named as subjects have appeared on Forbes' list of billionaires in 2018, 2019, or 2020, according to an analysis by ICIJ and BuzzFeed News.

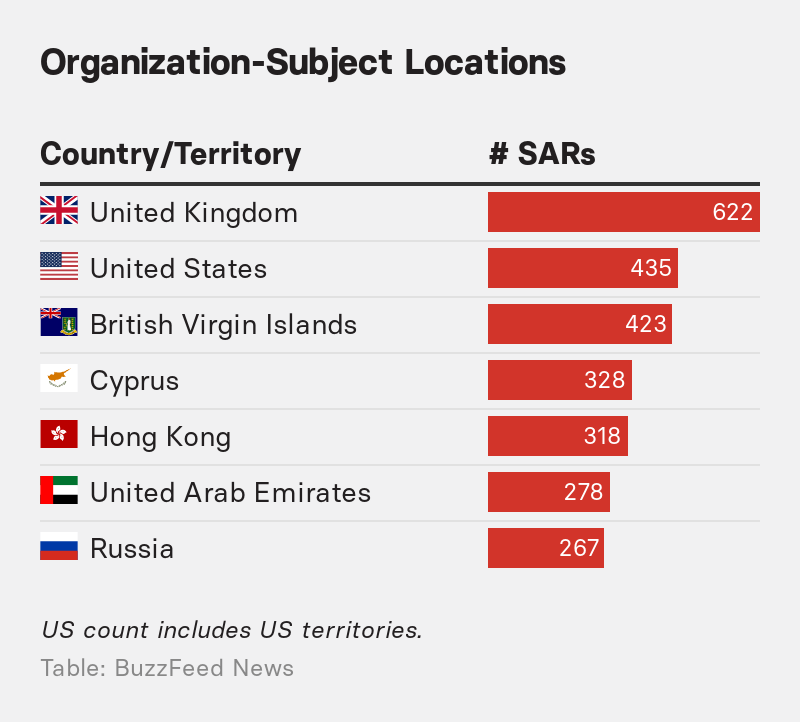

The SARs, however, are far more likely to mention organizations than people. The locations of those organizations read like a where’s where of wealth accumulation and management. More than 400 feature companies with addresses in the British Virgin Islands, and more than 300 include Hong Kong — two popular places for stashing wealth with little scrutiny.

More than a fifth of the SARs in the FinCEN Files include a subject whose “address” is effectively blank: no street number, city, state, or even country. In some cases, the blank addresses are for customers in the bank’s own corporate network.

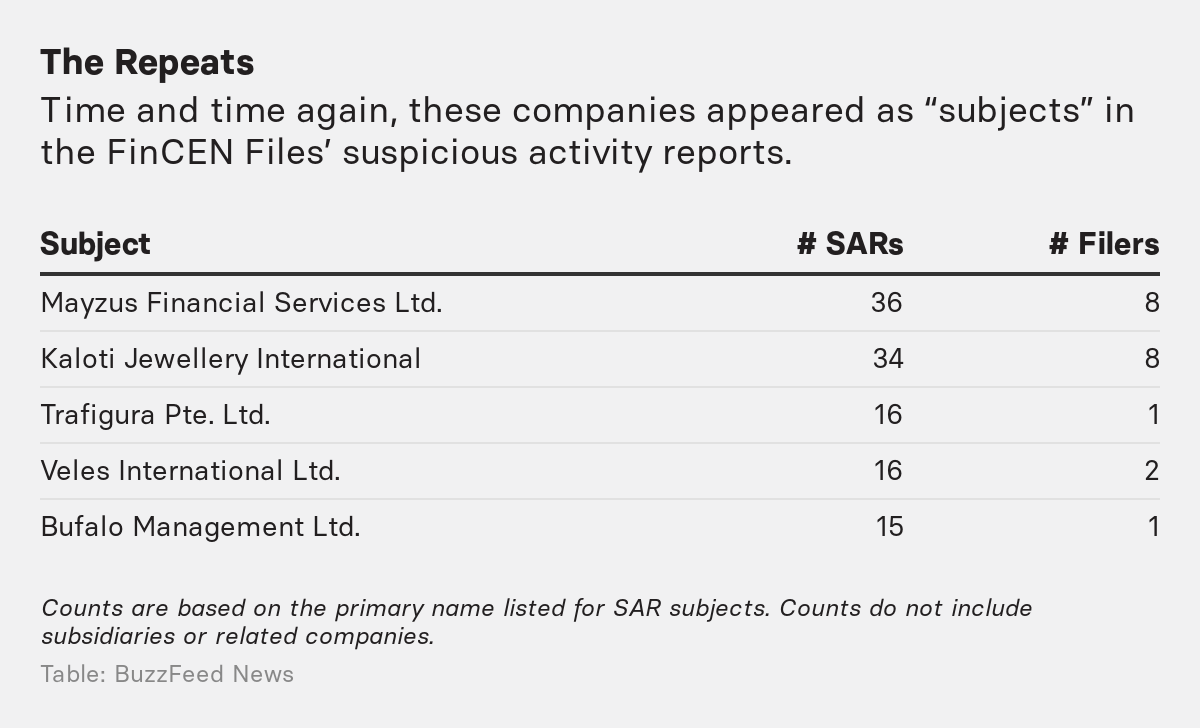

Some entities have been flagged numerous times in the FinCEN Files. Mayzus Financial Services, an online payment processing company that served clients involved in a bitcoin money laundering ring, sets the record, appearing as a subject of 36 SARs. Second is Kaloti Jewellery International, a Dubai-based precious metals company that was flagged as a subject in 34 separate SARs by eight different banks. Here are the five subjects flagged most often:

Responding to a request for comment, a representative for Mayzus Financial Services said the company takes compliance seriously and "helped to arrest online and offline fraudsters, corrupt remittance agents, money launderers, and apprehend hundreds of millions of dollars worth of illicitly gained assets" and that "from my perspective MFS has done exactly what it was supposed to be doing."

A lawyer for Kaloti said that the number of SARs was "statistically insignificant" in the context of its industry. "Kaloti vehemently denies any allegations of misconduct, whether those allegations stem from today or a decade ago," the company told ICIJ and BuzzFeed News.

Trafigura declined to comment. Veles International and Bufalo Management did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ inquiries.

What the Government Doesn’t Know

Last year, banks and other financial institutions filed more than 2 million SARs. Government investigators who combat money laundering told BuzzFeed News that the sheer volume of SARs made it impossible to pay close attention to them all.

"I don't think that we have enough resources in the government to meaningfully go through them all," said Richard Elias, a former federal prosecutor for the Eastern District of California.

Although the number of SARs filed grows every year, FinCEN’s staff has shrunk by more than 10% over the past decade, according to official Treasury reports. (In addition to full-time staff, FinCEN also employs contractors to analyze SARs.) In 2017, FinCEN’s acting director testified before Congress that the agency faced hiring issues, in part because of how long it takes to get security clearances.

FinCEN did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ requests for comment about its investigative findings. It did, however, release a statement saying that “the unauthorized disclosure of SARs is a crime,” and it announced that it was referring the matter to the Department of Justice and the Treasury Department’s Office of Inspector General.

FinCEN makes its database of SARs available to more than 450 law enforcement and regulatory agencies around the country, with more than 13,000 users who query the system millions of times a year.

FinCEN does not require banks to file spreadsheets detailing each individual transaction, although some do so voluntarily. Yet it’s precisely those details that investigators say are most important. “There's nothing of greater value than being able to take a look at a series of wire transfers or a series of deposits or a series of withdrawals,” said Peter Djinis, a former FinCEN analyst who helped to set up the original SAR system. “All of that information is so useful.”

When banks don’t attach transaction files, analysts have to comb through each report individually or request those records directly.

The database produced by BuzzFeed News and ICIJ provides far more clarity than the individual filings themselves, and has already helped our international network of reporters examine failures by governments and banks to stem the flow of dirty money across the globe. ●

Emilia Díaz-Struck and Agustin Armendariz of ICIJ contributed reporting.