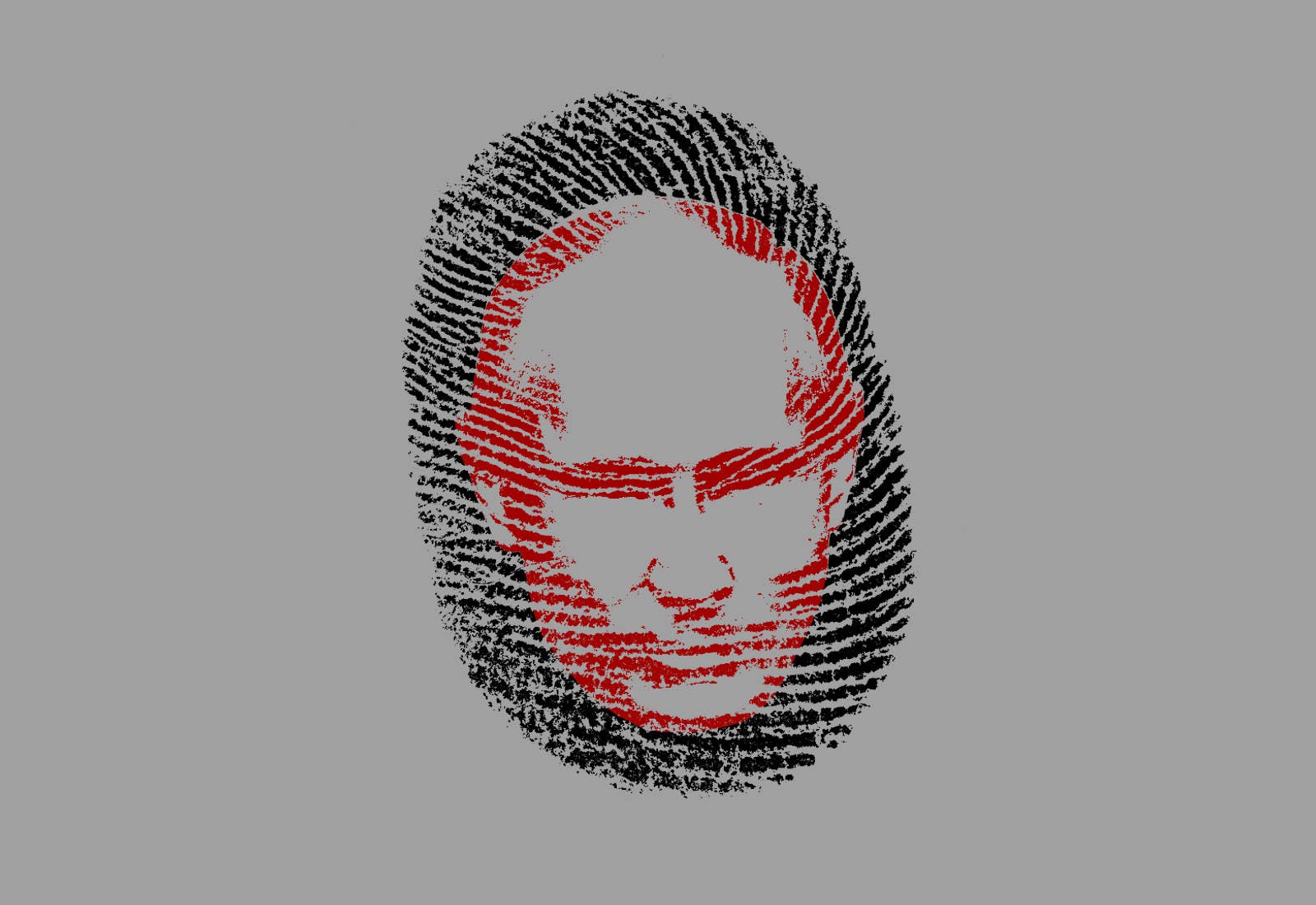

The fingerprint-analysis software used by the FBI and more than 18,000 other US law enforcement agencies contains code created by a Russian firm with close ties to the Kremlin, according to documents and two whistleblowers. The allegations raise concerns that Russian hackers could gain backdoor access to sensitive biometric information on millions of Americans, or even compromise wider national security and law enforcement computer systems.

The Russian code was inserted into the fingerprint-analysis software by a French company, said the two whistleblowers, who are former employees of that company. The firm — then a subsidiary of the massive Paris-based conglomerate Safran — deliberately concealed from the FBI the fact that it had purchased the Russian code in a secret deal, they said.

In recent years, Russian hackers have gained access to everything from the Democratic National Committee’s email servers to the systems of nuclear power companies to the unclassified computers of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, according to US authorities.

This September, the Department of Homeland Security ordered all federal agencies to stop using products made by the Moscow-based company Kaspersky Lab, including its popular antivirus software, and media outlets reported that Russian hackers had exploited it to steal sensitive information on US intelligence programs. The department later clarified that the order didn’t apply to “Kaspersky code embedded in the products of other companies.” The company’s founder, Eugene V. Kaspersky, has denied any involvement in or knowledge of the hack.

The Russian company whose code ended up in the FBI’s fingerprint-analysis software has Kremlin connections that should raise similar national security concerns, said the whistleblowers, both French nationals who worked in Russia. The Russian company, Papillon AO, boasts in its own publications about its close cooperation with various Russian ministries as well as the Federal Security Service — the intelligence agency known as the FSB that is a successor of the Soviet-era KGB and has been implicated in other hacks of US targets.

“The fact that there were connections to the FSB would make me nervous to use this software.”

Cybersecurity experts said the danger of using the Russian-made code couldn’t be assessed without examining the code itself. But “the fact that there were connections to the FSB would make me nervous to use this software,” said Tim Evans, who worked as director of operational policy for the National Security Agency’s elite cyberintelligence unit known as Tailored Access Operations and now helps run the cybersecurity firm Adlumin.

The FBI’s overhaul of its fingerprint-recognition technology, unveiled in 2011, was part of a larger initiative known as Next Generation Identification to expand the bureau’s use of biometrics, including face- and iris-recognition technology. The TSA also relies on the FBI fingerprint database.

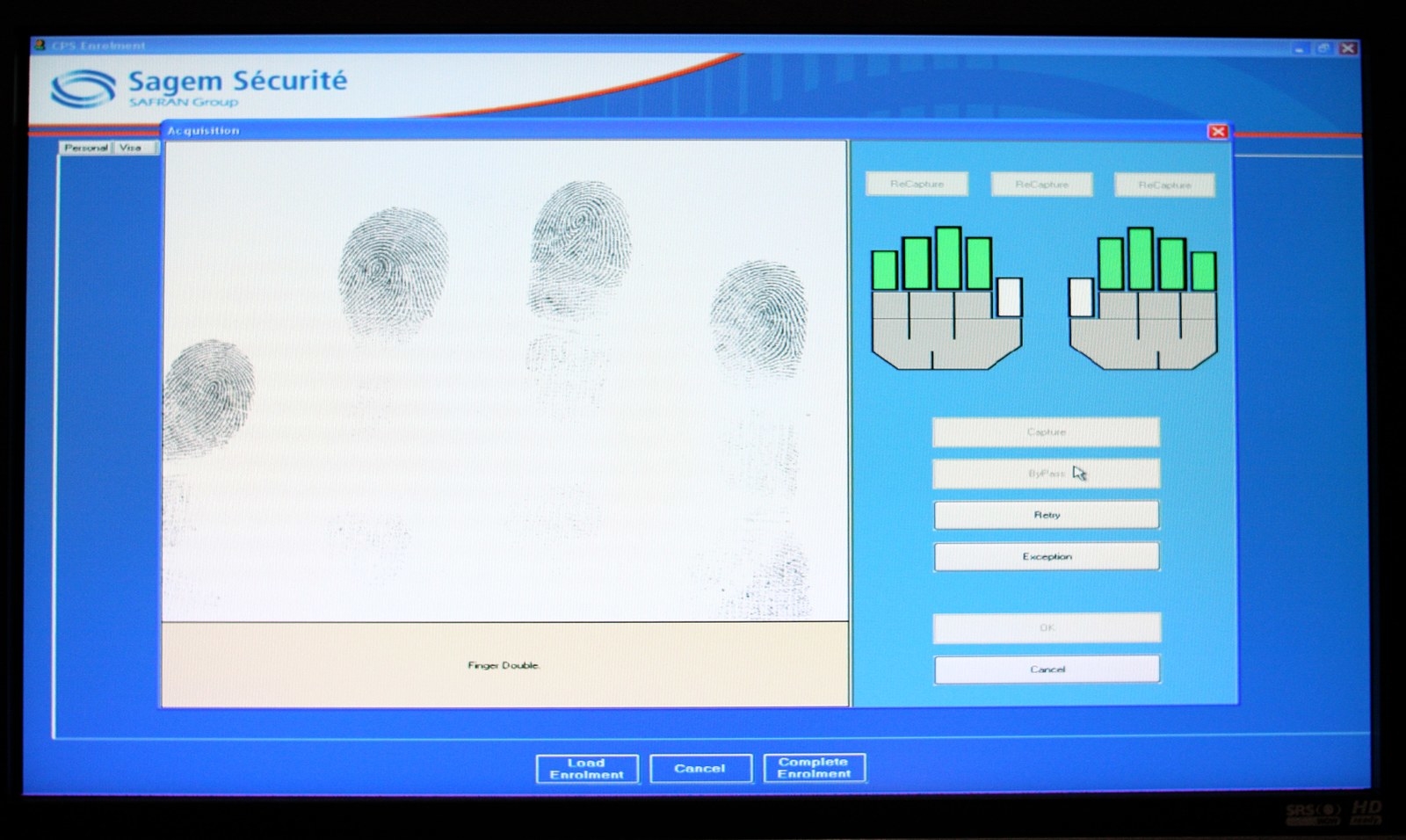

In hopes of winning the FBI contract, the Safran subsidiary Sagem Sécurité, later renamed Morpho, licensed the Papillon technology to boost the performance of its own fingerprint-recognition software, the whistleblowers said. Both of them worked for Morpho: Philippe Desbois was the former CEO of the company’s operations in Russia, and Georges Hala worked for Morpho’s business development team in Russia.

BuzzFeed News reviewed an unsigned copy of the licensing agreement between the French and Russian companies, which both men said they had obtained while working for Morpho; it is dated July 2, 2008 — a year before the company beat out some of the world’s largest biometric firms, including an American competitor, to secure the FBI business. It grants Sagem Sécurité the right to incorporate the Papillon code into the French company’s software and to sell the finished product as its own technology. It also stipulates that Papillon would provide updates and improvements during the five-year period that ended on the last day of 2013. In return, Sagem Sécurité agreed to pay an initial fee of roughly 3.8 million euros — equivalent to almost $6 million at the time — plus annual fees.

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

The contract, which is also referenced in court documents, says that to Papillon’s knowledge its software does not contain any “undisclosed ‘back door,’ ‘time bomb,’ ‘drop dead,’ or other software routine designed to disable the software automatically with the passage of time or under the positive control of any person” or any “virus, ‘Trojan horse,’ ‘worm,’ or other software routines or hardware components designed to permit unauthorized access, to disable, erase, or otherwise harm the software, hardware, or data.”

The contract reviewed by BuzzFeed News also contains a section titled “Publicity” that says, “The parties agree to keep strictly confidential and not to disclose by any means to any third party the existence and the contents of this Agreement.”

Desbois — who has filed a whistleblower lawsuit in US federal court accusing Safran of fraudulently collecting about $1 billion from federal, state, and local agencies — said at least three high-level company officials stressed to him on multiple occasions that the existence of the agreement needed to remain a closely held secret. Disclosure, he said he was told, might jeopardize contracts in the US market, which the company coveted.

“They told me, ‘We will have big problems if the FBI is aware about the origin of the algorithm.’”

“They told me, ‘We will have big problems if the FBI is aware about the origin of the algorithm,’” he recalled.

Neither Desbois nor Hala was personally involved in the integration of Papillon code into the French company’s products or the sale of the software to the FBI, but both said they had conversations with engineers who did work on the integration. Desbois said multiple company officials told him that the technology sold to the FBI contained the Papillon algorithm.

“You know the word omertà?” Desbois said, referencing the Mafia code of silence made famous by the movie The Godfather. “It was always the intonation like we have done something bad that is a secret between us and that we should not repeat it to anybody.”

“Deep collaboration”

In promotional material and on its website, Papillon boasts of its work with Russia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, which oversees police and immigration agencies, among others, and is run by a longtime police official who was appointed to the post in 2012 by President Vladimir Putin. The products that Papillon sells “are created with the instructional assistance” of the ministry, and the company is “closely cooperating with the Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Justice of Russia,” according to company publications. A Russian government website says that the Internal Affairs Ministry “renders methodic assistance” to Papillon.

“Papillon is not an independent company,” said Hala, one of the whistleblowers. “Papillon was an emanation of the Internal Affairs Ministry, so Papillon was always under the control of the ministry.”

Papillon’s deputy director for marketing, Ivan Shapshal, disputed that. “We are fully a private company,” he said. “Do we do special tasks for the intelligence agencies of Russia? No, there is no reason for us to do this. It is just a risk. It does not help us make money.”

Among the Russian agencies that use the company’s fingerprint-recognition technology is the FSB. “Year by year,” one Papillon publication says, “the company expands its cooperation with” the FSB, as well as Russian agencies in charge of immigration, customs, and drug control. Other clients include the governments of Turkey, Kazakhstan, Serbia, and Albania.

“We will be happy to be close to any security agency in the world for money.”

Shapshal said his company’s fingerprint-recognition technology helps Russian police solve roughly 100,000 cases per year. “If our software can help police solve more crimes, we are happy to be ‘very close’ to them, as you say,” he said. “We will be happy to be close to any security agency in the world for money.”

Papillon’s founder and director is Pavel Zaitsev, who worked as an engineer and programmer at Russian military installations from 1985 to 1991, according to a biography published with an article he wrote for a trade publication. Many of the company’s staffers, a Russian government website says, “gained experience working at the plants of Military-Industrial Establishment in Miass” — the city in the Ural Mountains where the company later established its headquarters.

Hala said there was “deep collaboration” between Papillon and the FSB. “It’s not a secret,” he said. Hala said he attended multiple meetings involving Russian government officials and Papillon executives in which FSB officials expressed strong support for Papillon and “controlled absolutely the discussion.”

The Internal Affairs Ministry, the FSB, and the Russian Embassy in Washington, DC, did not respond to requests for comment.

Neither the FBI nor any of the companies involved denied directly that the fingerprint software used by the bureau contains Russian code.

The FBI declined to answer repeated questions about the software but said in a statement, “As is typical for all commercial software that we operate, appropriate security reviews were completed prior to operational deployment.”

Safran declined to respond to questions about its actions as owner of the subsidiary that provided the software to the FBI, noting that it has since sold that subsidiary. But in legal filings, Safran has not denied the existence of the contract to license the Russian code, instead arguing that the allegations of fraudulent sales were not specific enough and that the company was not legally responsible for the actions of its subsidiary.

Safran sold the subsidiary this year to a US private-equity firm, which renamed the company Idemia. An Idemia spokesperson said the fingerprint-recognition technology was “almost entirely developed and manufactured in France or in the United States” but that two software components contained source code developed “by other companies.”

The spokesperson, Céline Stierlé, refused to name those companies.

“We don’t comment on such things because we cannot confirm or deny.”

More broadly, she said the whistleblowers’ claims “are old allegations that are not supported by facts and that have been rejected by federal and state authorities and by the courts,” referring to the lawsuit filed by Desbois, one of the former employees who spoke with BuzzFeed News.

This year, a federal judge dismissed the case but did not evaluate the merits of most of the allegations. Instead, the judge focused on technical issues, finding that the suit hadn’t alleged enough specifics about, for example, when and how fraudulent claims for payment may have been submitted to the government. Also, the judge wrote, any false claims would have been submitted by a subsidiary that was not named as a defendant in the case — and the parent companies that were named couldn’t necessarily be held legally responsible. The case is on appeal.

As for the Russian company, Papillon, executive Shapshal responded to a question about the contract giving the French company rights to its code by saying, “We don’t comment on such things because we cannot confirm or deny.”

But he insisted that the company’s code did not include any vulnerabilities, saying that if anyone were to check “then you will see there is no back door.”

“Weigh carefully the risks”

As the FBI evaluated the companies vying to provide the fingerprint-recognition software in 2009, the possibility that the contract might go to a company subject to influence by a foreign government, even an ally, unsettled some members of Congress. The part-ownership of Safran by the French government prompted a letter to then-FBI director Robert Mueller from former Rep. John Kline of Minnesota, a Republican member of the House Intelligence Committee.

“Allowing a foreign government to provide services regarding sensitive information to our law enforcement and intelligence communities could potentially pose a grave counterintelligence threat to the US government,” Kline wrote. “I urge the FBI to assess whether any domestic companies are capable of this work and weigh carefully the risks versus the benefits of granting a foreign government access to this sensitive data.”

“Allowing a foreign government to provide services regarding sensitive information to our law enforcement and intelligence communities could potentially pose a grave counterintelligence threat.”

An FBI spokesman at the time said that the bureau “assesses all risks and vulnerabilities associated with any foreign influence or security concerns for vendors under consideration for contracts, including subcontracts, with the FBI.”

Later that year, the FBI and Lockheed Martin — the primary contractor in charge of incorporating various vendors’ products into the bureau’s system — announced the selection of a Morpho subsidiary, MorphoTrak. Among the competitors not chosen was the US company Cogent Systems.

A Lockheed Martin spokesman refused to discuss the contracting process and said the company had divested its unit responsible for the FBI program. A representative for Leidos, which is now the project’s primary contractor, declined to comment.

Desbois’s whistleblower lawsuit alleges that a US-based MorphoTrak engineer named Frank Barret was aware of the Papillon deal and led a team that helped prepare the software for use by the FBI. On the front step of his home in California, Barret refused to read and respond to the allegations in the complaint but said, “Everything I’ve said to the investigators, everything I’ve said in this trial, is true.” Asked to clarify, he closed his front door. When BuzzFeed News followed up the next day, Barret threatened to call the police.

Both Desbois and Hala said they discovered the existence of the agreement licensing the Russian company’s code after they questioned their bosses’ instructions not to compete with Papillon for certain contracts. It was then, they said, that company officials explained that the two companies had an unwritten agreement not to encroach on each other’s business in certain countries — an arrangement that violates antitrust laws, the whistleblower claim alleges. Desbois and Hala said that they obtained a copy of the licensing agreement because they wanted to see for themselves whether it spelled out the terms of the noncompete pact; it did not.

Papillon executive Shapshal declined to comment on the antitrust allegations. Idemia spokesperson Stierlé said that “this allegation, like the others, was part of the litigation” and that “it too was found to be deficient and lacking in even the most basic level of detail and was rejected by the court.” The judge found that the whistleblower suit did not provide specifics on who falsely certified to the US government that the company hadn’t violated antitrust laws, or when and how this had occurred.

Desbois’s whistleblower lawsuit accuses Safran of defrauding the US government out of about $1 billion, and if the suit is successful he stands to collect millions. Hala is not involved in the case. Both Desbois and Hala said they left Morpho voluntarily and on good terms.

The federal government so far has declined to intervene in the lawsuit, as it has the option to do in whistleblower suits alleging fraudulent claims for payment. In court filings, however, Justice Department lawyers noted that this wasn’t necessarily an indication that the case lacked merit, and they preserved their right to step in later. The complaint also accuses the defendants of misrepresenting the fingerprint technology in sales to the government of California; lawyers for the state also have declined to intervene.

The FBI contract is now a centerpiece in much of MorphoTrak’s marketing material. In 2011, the FBI said the new fingerprint-recognition software significantly increased both the speed and accuracy of matches, boosting the latter from 92% to more than 99.6%.

“In terms of prestige, to be able to say ‘My technology is used by the FBI,’ it really helps with sales.”

“In terms of prestige, to be able to say ‘My technology is used by the FBI,’ it really helps with sales,” said former employee Stephane Guichard, who led a US-based team that implemented and maintained the fingerprint-matching software for state and local agencies that had purchased it but was not involved in the software’s development or the FBI contract.

Guichard and two other former MorphoTrak employees who worked on government contracts in the US said they didn’t know about the licensing agreement with Papillon, and they expressed surprise that their former employer would use Russian technology. “Personally, it would have concerned me a little bit,” said Phillip Moore, who worked as an account manager and sales manager. It would have raised “basic trust issues with what they would supply us,” he said.

By the end of 2013, as the final stage of the FBI project phase-in became operational, Morpho reported that the US market accounted for more than a third of its roughly $2 billion in revenues.

Safran recently announced that it planned to refocus solely on aerospace and defense, and, earlier this year, it sold Morpho, which had recently been renamed Safran Identity & Security, to the US private-equity firm Advent International, with the French government investment bank Bpifrance also taking a stake. The reported price was about $2.5 billion.

The company, now named Idemia, has provided fingerprint-recognition software to the Department of Defense and agencies in 28 states and 36 cities or counties across the US — from the Orange County Sheriff’s Department to the New York Police Department. Through its subsidiaries, Idemia is a powerful lobbying force in Washington, and it is currently fighting to kill legislation that would endanger its status as the sole provider of fingerprint services for the TSA PreCheck program. ●