When Robert Meltzer, who runs gyms for children in Los Angeles, found that more than $60,000 in payroll taxes — half a year’s worth — had gone missing in 2013, it was too late.

When something similar happened to Stanford Media Group, a company that sold CDs and DVDs online, Mark Gilula said he was forced to lay off employees. He said the stress contributed to his heart attack.

And when Maureen Sullivan, an architect, went looking for answers about the $111,000 that evaporated from her accounts, she said her inquiries with the police “basically went into a black hole.”

What none of these small business owners could have known was that their losses were linked to one of the most infamous international banking scandals on record.

The bookkeeper who handled their payroll allegedly embezzled their money and injected it into a notorious scheme used by crime bosses, terrorist financiers, and drug cartels. The participants laundered $10 billion of illicit money into nice clean cash.

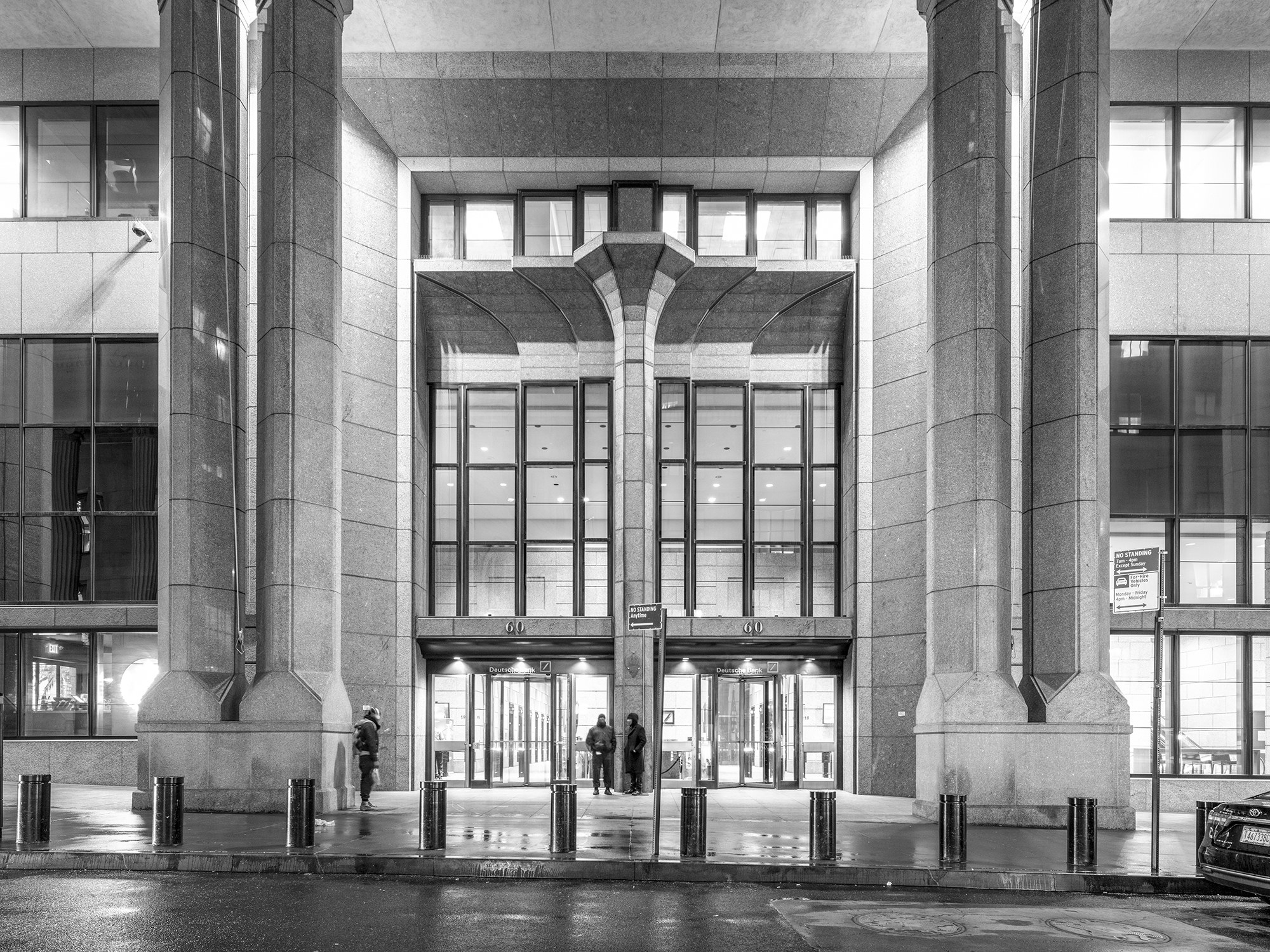

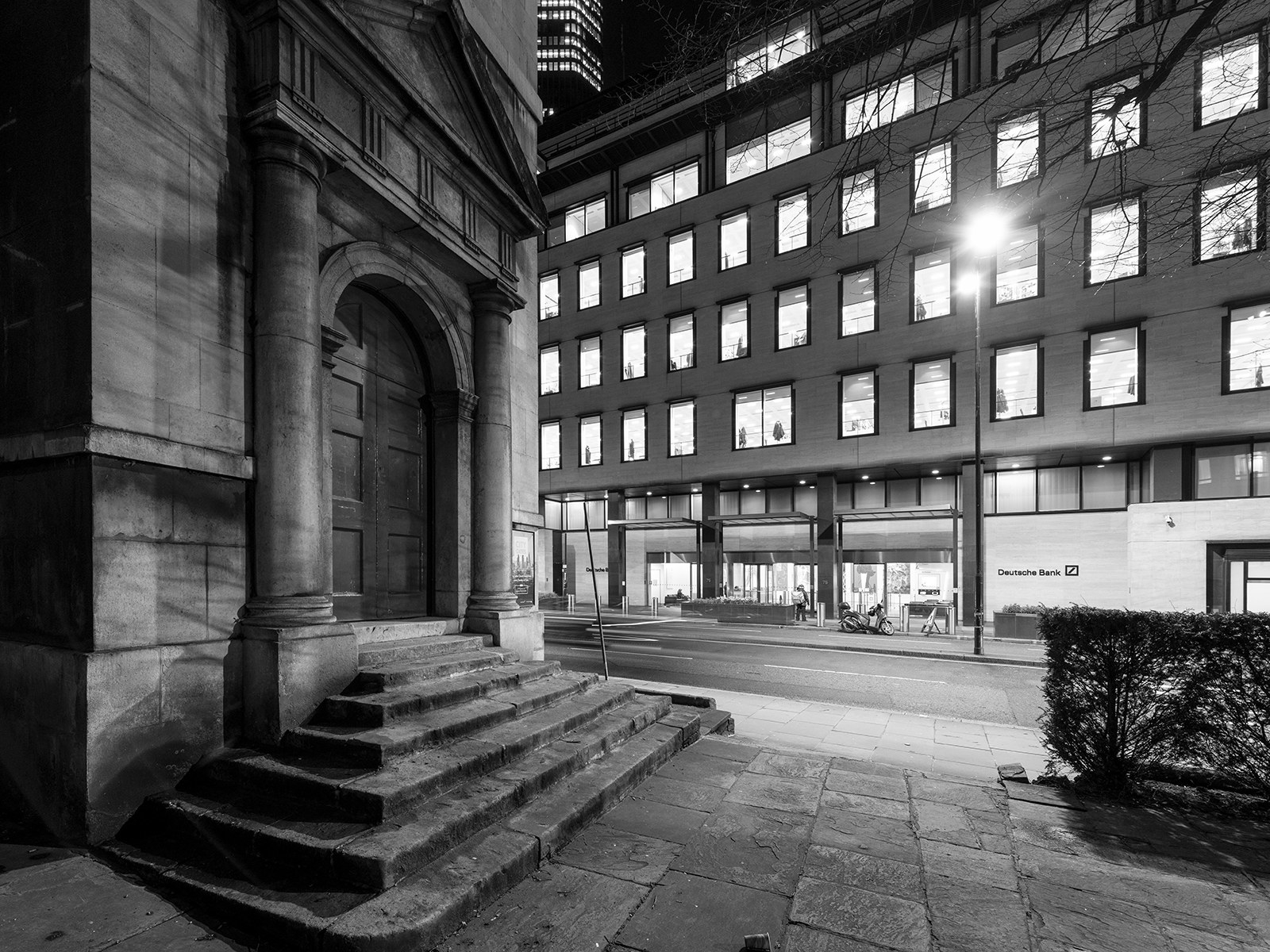

It all happened with the help of Deutsche Bank, Germany’s biggest financial institution and one of the biggest lenders to Donald Trump. But when the enormous scandal broke, Deutsche blamed it on a few middle-level staffers in its Moscow office, paid a fine, and got back to business.

The FinCEN Files investigation reveals that Deutsche managers, including top executives, had direct knowledge for years of serious failings that left the bank vulnerable to money launderers. Documents show two warnings sent to committees that included Paul Achleitner, Deutsche’s chair, and one sent to the bank's supervisory board.

Deutsche’s problems were so striking they prompted Bank of America to file a confidential alert known as a suspicious activity report, or SAR, to the US government. Bank of America employees had visited Deutsche’s London office to discuss worries about Russian money laundering. They were stonewalled when a Deutsche manager interrupted their meeting and asked them to leave the building. Bank of America found the situation troubling enough that it raised the matter with Achleitner, according to its filing.

Another top Deutsche executive, Christian Sewing, ran the audit division when one of its teams gave the Moscow office a clean bill of health, despite evidence that it could not even produce a list of its clients, let alone verify that they were who they said they were. Sewing is now Deutsche’s CEO.

In all, more than 100 internal alerts were raised on the companies at the heart of the Russian mirror trade scandal between 2012 and 2015.

During these years, some of the world’s worst criminals used the network to move dark money around the globe, with the help of shell companies and corrupt financiers. Business owners like Meltzer, Gilula, and Sullivan were left to pick up the pieces. The wide range of criminal activity linked to the mirror trades has never before been revealed.

The FinCEN Files investigation includes thousands of closely held US Treasury documents — among them, suspicious activity reports — that BuzzFeed News shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and more than 100 newsrooms around the world. This investigation is also based on confidential bank documents obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, a partner in this project.

By law, banks must file SARs to the Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, when they spot activity that bears the hallmarks of money laundering or other financial misconduct. SARs by themselves are not evidence of a crime, but they can support investigations and intelligence gathering.

In recent years, Deutsche’s share price has plummeted under the weight of scandal after scandal. In the last decade, the bank has paid fines for everything from evading sanctions against Iran and Myanmar to rigging foreign exchange markets to doing business with Jeffrey Epstein. And it has come under scrutiny for lending Trump hundreds of millions of dollars despite his history of defaulting on loans.

The bank, responding to questions raised by this investigation, said it has acknowledged “past weaknesses” and “learnt from our mistakes,” while investing hundreds of millions of dollars to bolster its defenses against financial crimes. “We are a different bank now,” a Deutsche spokesperson said in a written response.

The spokesperson said Sewing was not personally involved in the review of the Moscow office and disputed aspects of Bank of America’s written account to the government, including the assertion that Achleitner met with an executive from that bank.

The $10 billion mirror trading scheme remains one of Deutsche’s darkest stains. While it had many tentacles, at its heart was a group of money launderers who controlled a network of anonymous companies around the world.

They would buy shares in Russia and sell the stock to one of the European shell companies they owned. As the network pinged money across the globe, it turned the rubles into dollars and other currencies. The system had one other great advantage: It allowed criminals to move their ill-gotten gains undetected.

To make it all happen, the perpetrators needed a Western bank to work with them. They found one in Deutsche. It wasn’t the only bank that was involved, but prosecutors said traders in its Moscow office were motivated by “greed and corruption” and that one supervisor had apparently been bribed to facilitate the trades.

The companies that moved the money were some of Deutsche Russia’s most active clients, at times generating bigger commissions for the bank than any of its other customers in Russia.

In one confidential letter from March 2016, never before revealed, the UK’s financial regulator privately scolded Deutsche’s willingness to take on “very profitable clients, regardless of financial crime risks.” It cautioned that “leadership on financial crime had been lacking for a considerable period of time.”

But when the agency spoke about the matter publicly, it exonerated senior managers, saying they “were not aware of the suspicious trading” and the failings at the bank had been committed “negligently, rather than deliberately or recklessly.” The regulator initially considered a fine of £1.7 billion for the scandal, but decided that would be “disproportionately high” and reduced it to £163 million.

Among the recipients of cash from the mirror trades was a company the US government says is part of the Russian mafia.

The state of New York imposed a higher fine of $425 million but took the occasion to praise the bank’s leaders for dealing with the issue in a “serious manner and timely fashion.”

Among the recipients of cash from the mirror trades, the FinCEN Files investigation has found, was a company the US government says is part of the Russian mafia. Its owner has been identified as a liaison for Vladislav “Blonde” Leontyev, described by US authorities as a Russian mobster and a high-level narcotics trafficker. In response to BuzzFeed News, Leontyev denied any involvement in the mirror trades or other criminal activity.

Between March 2013 and April 2014, nearly $50 million in illicit funds also went to a company that is part of the Khanani money laundering organization, whose clients include Hezbollah associates, the Taliban, and Mexican drug cartels, according to the US government. (The group’s head, Altaf Khanani, was sentenced in 2017 to 68 months in prison after he laundered more than $1 million during an undercover Drug Enforcement Administration sting.)

A sporting goods supplier in Brooklyn, where the manager was found guilty of laundering money for cyberscammers, also received cash from the mirror trades. So did a New Jersey telecoms operation that did business with shell companies linked to organized crime, the Syrian weapons program, and a notorious oligarch, SARs show.

Money from a looted Russian bank where Vladimir Putin’s cousin sat on the board was also filtered into the network, records show.

All those funds were funneled into the money laundering operation along with cash from LA Payroll, the tax consulting firm whose owner allegedly defrauded 141 small businesses across Southern California. The victims included churches and not-for-profit organizations. The man behind the fraud fled the US and the money has never been recovered.

The saga of the mirror trades is not yet over for Deutsche. In its most recent annual report, Deutsche said that the Department of Justice continues to investigate, and that the bank had set aside money in case of future fines.

It started with a client called Financial Bridge, a small Russian firm that used Deutsche to buy and sell shares for its clients.

Financial Bridge was at the center of the mirror trading network, which by 2011 was already funneling hundreds of thousands of dollars to a front for the Brothers’ Circle — a group of organized criminals that the US government sanctioned for drug smuggling, human trafficking, and violence in Russia and around the world.

That same year, Russian authorities suspended Financial Bridge’s trading license on suspicion of money laundering. That should have triggered a review inside Deutsche, an outside consultant later determined. But when the ban was lifted, Deutsche’s Moscow office went right back to handling Financial Bridge’s transactions.

One of the company’s owners, a Ukrainian financier named Alexander Perepilichnyy, dropped dead during a jog outside his home on the outskirts of London.

Then, in November 2012, an even brighter red flag arose. One of the company’s owners, a Ukrainian financier named Alexander Perepilichnyy, dropped dead during a jog outside his home on the outskirts of London. Two weeks after he died, it was revealed that Perepilichnyy was linked to a multimillion-dollar tax fraud and had fled Russia, blowing the whistle on the scam.

A few weeks later, the documents obtained by Süddeutsche Zeitung show, Deutsche’s anti–money laundering software flagged Financial Bridge for its “high-risk transactions.”

But the alert went to an office in India where staff had “very limited” training, confidential regulatory documents show. Financial Bridge’s explanation for its transactions — that they were for “investment activities” — was deemed adequate.

By 2013, Deutsche’s own internal reviews were beginning to identify crucial weaknesses in the bank’s procedures for combating financial crime.

To guard against financial crimes, banks have policies to “know your customer,” which means researching clients before taking them on. But an internal review focusing on know-your-customer protocols in the Moscow office found that bankers there failed to properly vet clients, even neglecting to determine if they were known criminals. The Moscow bankers could not even produce a list of who their clients were.

A separate, simultaneous review found that the Moscow office’s anti–money laundering department was severely short-staffed and failing to properly monitor transactions.

The findings of both of those reviews were shared with the Deutsche executive team. At one presentation, executives identified the situation as an “immediate priority.”

Achleitner was then chair of the supervisory board for Deutsche and sat on board committees. Documents show that these bodies were informed of anti–money laundering problems at the bank on at least three occasions in 2013 and 2014.

Those updates for board members included descriptions of how the bank was struggling with its obligation to research clients and that it was facing technology and staffing issues for its compliance teams.

By 2014, Christian Sewing, a Deutsche lifer who had started as a 19-year-old apprentice in the small German city of Bielefeld, was working his way up the corporate ladder and was chief of Deutsche’s audit division, the bank’s internal watchdog.

That summer, a team from his division turned its attention to Moscow; by fall the investigation had concluded. Despite all their colleagues’ documented concerns, the auditors gave Deutsche’s Moscow office a “green” rating, records reviewed by BuzzFeed News show.

The office received a “satisfactory” rating for “Control Environment” and for “Management Awareness.” As for the office’s anti–money laundering and know-your-customer procedures — which the team was specifically instructed to evaluate — the auditors wrote nothing at all, the records show.

Despite all their colleagues’ documented concerns, the auditors gave Deutsche’s Moscow office a “green” rating.

Records show that Deutsche later examined the quality of the 2014 audit and determined it was inadequate.

Deutsche declined requests to interview Sewing, but a Deutsche spokesperson said that he “had no direct or indirect involvement in the 2014 audit.”

The spokesperson added: “That was consistent with the well-established protocols at the time concerning which audits were escalated to the Global Head of Audit.” Deutsche also said Sewing helped to uncover the mirror trades later.

By the start of 2016, the volume of Russian money flowing into the US financial system was raising alarms at Bank of America. A team of experts from the bank flew to Deutsche’s London office seeking answers.

A suspicious activity report would later provide a blow-by-blow account.

In a Jan. 11 meeting with Deutsche, the Bank of America team began to gain some insights as the head of Deutsche’s business intelligence team “revealed significant challenges” that “his staff had to navigate to perform enhanced due diligence on clients,” the SAR says.

But the meeting was interrupted when one of Deutsche’s managing directors arrived. He told the Bank of America investigators they were not authorized to talk to anyone in London and asked them to leave.

The SAR says that the matter was escalated within Bank of America, with one of its senior managers “scheduled to meet with Paul Achleitner” in a few days. The SAR adds, “Achleitner indicated the matter would be addressed” with the bank’s CEO at the time, John Cryan.

On Jan. 29, a Deutsche executive overseeing compliance gave Bank of America officials assurances that their questions would be answered.

On Feb. 11, Bank of America filed its SAR on Deutsche. It wrote to the government that it did not yet have “sufficient information to assess the adequacy of the Deutsche Bank’s current control environment.”

Bank of America declined to comment for this story. Asked about the SAR, Deutsche Bank responded that “our review of the situation indicates that the events did not take place as implied.”

It added: “It would not have been the place of Paul Achleitner to get involved managing the interactions with Bank of America, nor do we have any record of him doing so.”

The bank declined to make Achleitner available for an interview.

Weeks later, the Financial Conduct Authority, the UK financial regulator that had been conducting a confidential review of Deutsche, sent a set of disturbing findings to the bank.

The letter warned that “leadership on financial crime had been lacking for a considerable period of time” at the bank and that managers had put the pursuit of profit above its responsibilities to fight money laundering.

It said it found evidence of “financial crime risk being overridden by commercial drivers and in some cases a willingness to take on very profitable clients, regardless of financial crime risks.”

The regulator said there was a “significant risk” that money laundering at the bank was “going unreported or undetected.”

To those within the bank, it wasn’t news.

In October 2015, Deutsche had hired consultants from the accounting giant Deloitte to figure out what had gone wrong. Deloitte interviewed staffers, combed through emails, and examined trading data.

The bank laid the blame on Tim Wiswell, an American who ran the Deutsche Moscow trading desk. But according to a copy of the Deloitte report obtained by Süddeutsche Zeitung, there were systemic failings at the bank.

Going into detail on the Moscow audit, the report described how the team had given the office a positive rating even though auditors hadn’t properly tested the office’s money laundering prevention system. The report concluded that audits conducted by the division had “severe shortcomings” from 2012 onward.

Sewing, while not named in the report, was head of audit at the bank from June 2013 to December 2014. He then joined the bank’s management board, where his responsibilities included the audit division for another six months.

The report also did not name Achleitner specifically. But it described instances when concerns about broken anti–money laundering systems were flagged to board committees on which he sat. The problem of understaffing was raised repeatedly, and Deloitte concluded that the bank’s compliance teams had been “undermined by limited allocated resources.”

Deloitte also found that the bank’s transaction monitoring software had issued 108 alerts about the mirror trading companies between 2011 and 2015. Nonetheless, during that time Deutsche kept the transactions moving.

By the time regulators caught up with Deutsche, Wiswell was gone. He had decamped to Bali, where he now lives with his family, and did not respond to requests for an interview. He was pictured last year at the gala dinner of the Florence Biennale art festival, with a beaming smile on his face and a glass of champagne in his hand.

Homeland Security documents indicate that Tovmas Grigoryan, the Los Angeles bookkeeper who allegedly absconded with money from clients’ small businesses, fled the country, likely for Russia.

Following its investigation into Deutsche and the mirror trades, the New York State Department of Financial Services determined that “greed and corruption motivated” some of the bank’s Moscow employees. In a consent order that resulted in a fine for the bank, the department said there was evidence of around $3.8 million of alleged bribes going to one of the Moscow bankers and a close relative.

State and federal law enforcement authorities have never charged anyone at Deutsche in relation to the mirror trades.

Inside Deutsche, the bank sacked three people who had worked on the Moscow office audits. Deutsche said that “most senior managers referenced in the internal investigative reports are not at Deutsche Bank anymore.”

“Consequences have been taken where and as appropriate, including on the management board level,’’ the bank’s spokesperson said.

The spokesperson defended the actions of the supervisory board, saying it “diligently exercised its oversight responsibility.”

Achleitner remains in power at Deutsche. In 2018, his board forced out CEO John Cryan after a short three-year reign, citing sagging profits.

On a Sunday evening that April, Achleitner presented Deutsche’s board with his choice for a new CEO to bring the bank the stability it so desperately needed: Christian Sewing. The board approved. ●