Earlier this month, the FDA announced that it has received reports of about 50 cases of cancer in people who’ve had breast implants.

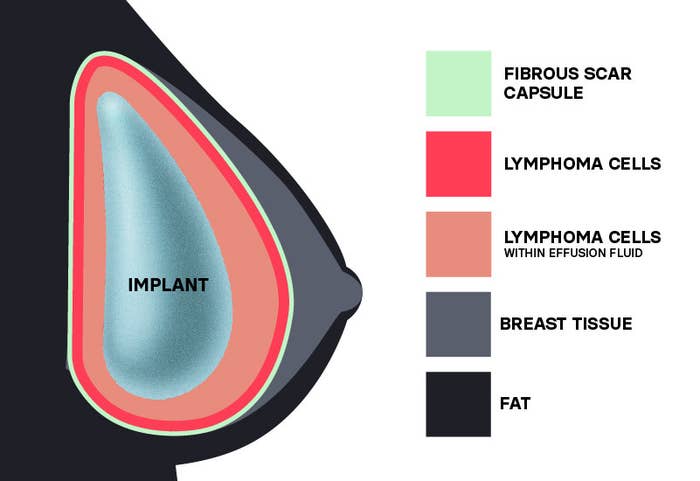

The cancers, including squamous cell carcinomas (a common skin cancer) and lymphomas, were found in the scar tissue that forms around implants. In some people, the cancer had spread throughout the body.

Some commonly reported symptoms included swelling, pain, lumps, and skin changes.

Although the warning is concerning, the experts we spoke to said the low number of cases so far is reassuring — and that implants will continue to be inserted per usual. The FDA said the risk of developing these cancers is rare, and there isn’t enough information to definitively say that breast implants are the cause of the cancers. It’s also not clear whether some types of implants carry greater risks than others; these cases are occurring across implant types (textured and smooth) and filling types (saline and silicone).

At this time, people with breast implants are not being encouraged to remove them.

Dr. Justin Broyles, a plastic surgeon at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said that about 400,000 people have implants surgically inserted under their breast tissue or chest muscles each year. About 300,000 of those are for cosmetic reasons, and the rest for reconstruction purposes — for example, following a mastectomy. So the “numbers in the grand scheme of things are relatively small,” he said.

Dr. Sarah Cate, a breast surgeon oncologist at Mount Sinai, agrees. She said that over 10 years, the incidence rate of these cancers is 0.00075%, or 1 in every 133,000 people. The FDA didn’t provide many details regarding the severity of the reported cancers and what kinds of treatments were used, Cate said, so it’s critical to avoid jumping to conclusions.

But this isn’t the first time cancer has been linked to breast implants. In 2011, the FDA identified a possible association between breast implants and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, a cancer of the immune system; as of April, 505 cases and 14 deaths have been reported in the US.

Still, the latest warning is a reminder that breast implants are intruders in the human body and that they carry some risks, including infection, ruptures, pain, problems breastfeeding, and more systemic symptoms informally known as “breast implant illness.” They also typically need to be replaced and are not a one-and-done procedure.

“Unfortunately, breast implants are not lifetime devices. Whether for reconstructive or aesthetic purposes, they serve a real role, but they're not perfect,” Broyles told BuzzFeed News. “Engaging in a conversation with your surgeon about the risks and benefits, and the durability of the devices in the follow-up, is really important for you to be an informed patient.”

Here’s everything to know about the common complications associated with breast implants and what to keep in mind if you already have or are planning on getting them soon.

What are the common complications of breast implants?

Breast implants carry inherent risks that increase the longer you have them, boosting the likelihood that you need to replace or remove the devices at some point.

It’s generally recommended that people replace their breast implants every 10 years, but that can change depending on any problems that may occur with your implants. Otherwise, MRI screenings are recommended five to six years after your surgery and then every two to three years thereafter. (Some insurance companies will not cover implant removal or replacement, despite complications.)

“It's not just a one-step procedure and then you don't ever have to see a plastic surgeon again,” Cate said. “It’s not like getting a haircut. You might have to go back to the operating room more than once, which is a serious consideration.”

Cancer aside, some other complications are bleeding, rippling, unexpected scarring, and changes in how your nipples or breasts feel, including pain or numbness. There are other potentially more serious issues that may require additional surgery to repair, including infection, ruptures or leaks, displacement, and capsular contracture (a painful hardening of the breast around the implant).

Generally, however, “these are really safe devices and most patients have a good experience,” Broyles said. There’s little data on how transgender patients fare with their breast implants, but early research shows that complications are rare and occur at the same rates as in cisgender patients.

Ruptures, for example, tend to occur anywhere between six to eight years after implantation. They can be caused by compression during a mammogram, normal aging of the implant, or — most commonly — damage done by surgical tools during the implant surgery.

Ruptures may not be obvious depending on the type of implant you have. Two types of breast implants are approved for use in the US: saline- and silicone-filled. (The latter are more popular because they tend to look and feel more natural, especially among reconstructive surgery patients who no longer have breast tissue to lay on top of the implants, Broyles said. Complications involving silicone breast implants first emerged in the 1960s. Safety concerns led the FDA to issue a “moratorium” or ban on the implants from 1992 to 2000, which officially ended in 2006 following receipt of safety and risk data on the devices.)

Patients with saline-filled implants know right away when their devices rupture, because it’s like a balloon of salt water that immediately deflates, but when silicone gel leaks out of an implant, it tends to stay in place without causing any breast shape change, Broyles said.

“That's why the FDA and plastic surgeons recommend monitoring with imaging to ensure that a rupture hasn't occurred,” Broyles said. “If you know you have a leak or rupture, I would definitely recommend replacing it or removing it.”

Another potential complication faced by some people who get some types of breast implants is trouble breastfeeding, especially for those who have had reconstruction after a mastectomy. It’s unknown if some silicone from an implant can pass through the device’s shell and into breast milk, but the FDA says at least one study shows this isn’t the case.

That said, there aren't any groups of people (based on age, race, or ethnicity, for example) that are more likely to experience any one of these complications, Broyles said, although mastectomy patients could face greater risks for certain events because their implant surgery tends to be more invasive.

Breast implant illness is as complex as it is controversial

Then there’s the more perplexing symptoms some people report feeling immediately after surgery or years later, such as fatigue, brain fog, rashes, GI issues, hair loss, anxiety, depression, weight changes, and muscle pain. Some, particularly those with predisposing risk factors or an existing condition, end up being diagnosed with autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory arthritis, lupus, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Clinicians call this “breast implant illness” (BII) or autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA). While some healthcare professionals believe BII is a specific disease, others aren’t convinced it’s real. Yet many patients, including celebrities Ayesha Curry, Crystal Hefner, Ashley Tisdale, and Yolanda Hadid, reported feeling relief from these symptoms immediately after their implants were removed.

BII is not currently recognized as a diagnosable medical condition and is generally not well understood. In a 2021 review, two researchers called it “the most controversial subject in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery.”

“There are certain diagnoses within medicine that can be hard for physicians to understand because there’s not an imaging test or lab value. This is one of those examples where it really involves a thoughtful conversation with the patient,” Broyles said. “When I have to remove breast implants in these cases, many times patients report feeling better, and I can’t necessarily explain that with a laboratory result or imaging finding.”

“But ultimately my job as a plastic surgeon is to make my patients feel and look their best and if that’s a result of that interaction, then I think it’s a worthwhile endeavor,” he added.

An analysis by the FDA of medical device reports posted between January 2008 and April 2022 identified 7,467 cases of BII. Most patients were about 42 years old, on average, and developed BII symptoms about five years after getting their breast implants. However, the FDA warns that these numbers are likely underestimated.

Textured implants may carry greater risks

Breast implants also come with smooth or textured surfaces, with varying shapes and degrees of thickness. It’s said that textured implants stay in place better than smooth ones because their ridges better adhere to surrounding muscles — especially, Cate said, for thinner patients, who have smaller pockets to fit them into — but they do have more of a bad rap.

Textured implants, which represent 10% of all breast implants sold in the US, made up a greater proportion of the more than 730 cases of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) globally.

Textured implants were involved in 496 of the 733 global cases of BIA-ALCL reported to the FDA (209 cases did not specify the implants involved); they were also involved in 16 of the 36 reported deaths (19 cases did not specify the implants involved). The majority of these textured implants came from the same pharmaceutical company, too.

The discovery prompted the FDA in 2020 to ask Allergan to recall all of its BIOCELL textured implants — accounting for less than 5% of all breast implants sold in the US — and textured tissue expanders, which are used to stretch the skin before implant surgery.

An analysis by the FDA found that the risk of BIA-ALCL with the BIOCELL textured implants was about 6 times higher than with textured implants from other manufacturers. But some estimates show the risk of BIA-ALCL may be more than twice as high as the FDA estimates. At least one case has been reported in a person with silicone implants, but the patient’s history with other implants is unknown.

Fortunately, most patients who receive surgery to remove their implants recover from BIA-ALCL successfully, with some needing chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

The FDA’s warnings about BIA-ALCL really took the “breast implant world by storm,” Broyles said, and they caused some hospital systems to forgo stocking textured implants altogether, Cate said.

Again, it’s unclear if the implant itself is causing the cancer, but experts speculate that something about its texture triggers a large inflammatory response that cascades out of control.

“But this is poorly understood because many, many patients have had textured implants and very few of them actually develop some of these cancers,” Broyles said. “I do upwards of 200 implant reconstructions a year and I have only seen one case of BIA-ALCL. Most surgeons will work their entire career and not see a case, so it is quite rare.”

What remains to be seen is how the risk of cancer differs between silicone- and saline-filled implants, the FDA says.

Overall, it’s a good idea to monitor your breast implants and contact your plastic surgeon if you notice any abnormalities.