My mother and two aunts held it down at the school board meeting 🙏🏾🫶🏾. And the book was not removed. Thanks for all the prayers y’all. 🥹🥹🫶🏾🫶🏾

George M. Johnson wasn’t surprised when they heard that their book All Boys Aren’t Blue was facing a ban at a public library in New Jersey. The 37-year-old author has seen their memoir banned in at least 29 school districts.

Last week, Glen Ridge United Against Book Bans invited Johnson to attend its library board of trustees meeting, hopefully to sway trustees to vote against the ban, but they had to be in Houston for a book reading. Instead, Johnson asked their mom and two aunts — who live 20 minutes away in Plainfield where Johnson grew up — to appear in their place.

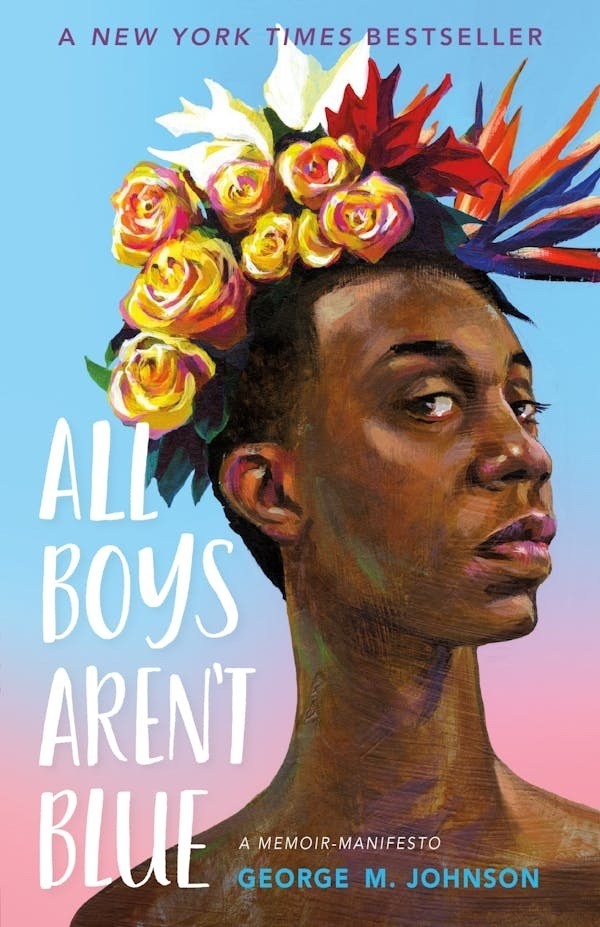

Amid a crowd of people both for and against the ban of Johnson’s book and five others that include representation of LGBTQ people, Kaye Johnson, 65, Johnson’s mother, took the floor to provide public comment. Behind her were her sisters, Stephanie Elder, 51, and Sarah Elder, 57, holding a poster of the cover of All Boys Aren’t Blue.

Johnson’s mother then powerfully read a statement prepared by her child to defend their work.

“Our books are not introducing teens to hard topics. They are simply the resource needed so they can understand the hard topics they are living out day to day,” Kaye Johnson said.

All Boys Aren’t Blue, which was released in 2020, is a collection of personal essays by Johnson about their childhood and adolescence for young adult readers. The book depicts topics including consent, agency, sex, and an instance of statutory rape.

The local group Citizens Defending Education had filed to remove Johnson’s book as well as Here and Queer by Rowan Ellis, This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson, It’s Not the Stork and It’s Perfectly Normal by Robie H. Harris, and You Know, Sex by Cory Silverberg.

“Not all parents want their children indoctrinated in race-based theories, reading sexually explicit material, or being taught in the classroom to question their sexuality or gender identity,” the group says on its website.

But Johnson’s defense of their book, as read by their mother, said it’s necessary for young people to access literature that grapples with Black and queer experiences.

“As a Black queer person, I know what it’s like to read books that don’t tell my story,” Johnson’s mother read. “So in this hunt to protect teens, does it ever cross your mind that removing or restricting this life-saving story for LGBTQ students only harms them more or how removing this life-saving story for Black teens harms them? Or do you not care? That’s really what this fight is over — removing LGBTQ stories and Black stories. If you don’t want your child to read it, that’s fine, you have every right to allow your child not to read, but you don’t get to trample on the rights of parents like my mother and my aunts.”

When Johnson’s family finished reading the statement, the room erupted into cheer. And after hearing from them and dozens of other community members, the Glen Ridge Public Library Board of Trustees voted unanimously to keep Johnson’s book and the others in circulation.

Though they couldn’t physically be there, Johnson told BuzzFeed News they received live updates about the meeting from their family group chat. They watched the video, feeling both honored and nervous for their mother and aunts, especially after hearing from them that police in riot gear had showed up to the meeting.

“It was really emotional because I hate that they have to get pulled into this. You never want your family to feel like they’re being targeted,” Johnson said. “On a micro level, it just feels good to have that type of support in my life and know that I always have that. But on a macro level, it was a beautiful thing for queer community to see what it looks like when a family shows up for you.”

Johnson said that since their book was released nearly three years ago, they have seen almost daily attacks from parent groups, schools, and libraries across the country trying to get it off the shelves.

In 2021, the American Library Association named All Boys Aren’t Blue the third-most-banned book in the US.

Johnson said in the past it was “fun” to keep track of each proposed ban on their book, but these days, it’s too time-consuming. When the book was first published, Johnson knew they might receive some pushback but never imagined that their memoir would still be at the center of culture war discussions over parental rights and education in 2023.

“I don’t think I ever at any moment thought I would be sitting here today still fighting the good fight — and still being removed,” Johnson said. “I’m like, is my book ever gonna fall off the [banned book] list? … I think it speaks volumes, though, like a Black book and queer book potentially being at the top of the most challenged list in the United States. It speaks volumes about the particular hatred of two groups in this country and how that hatred came out at the intersection of a person.”