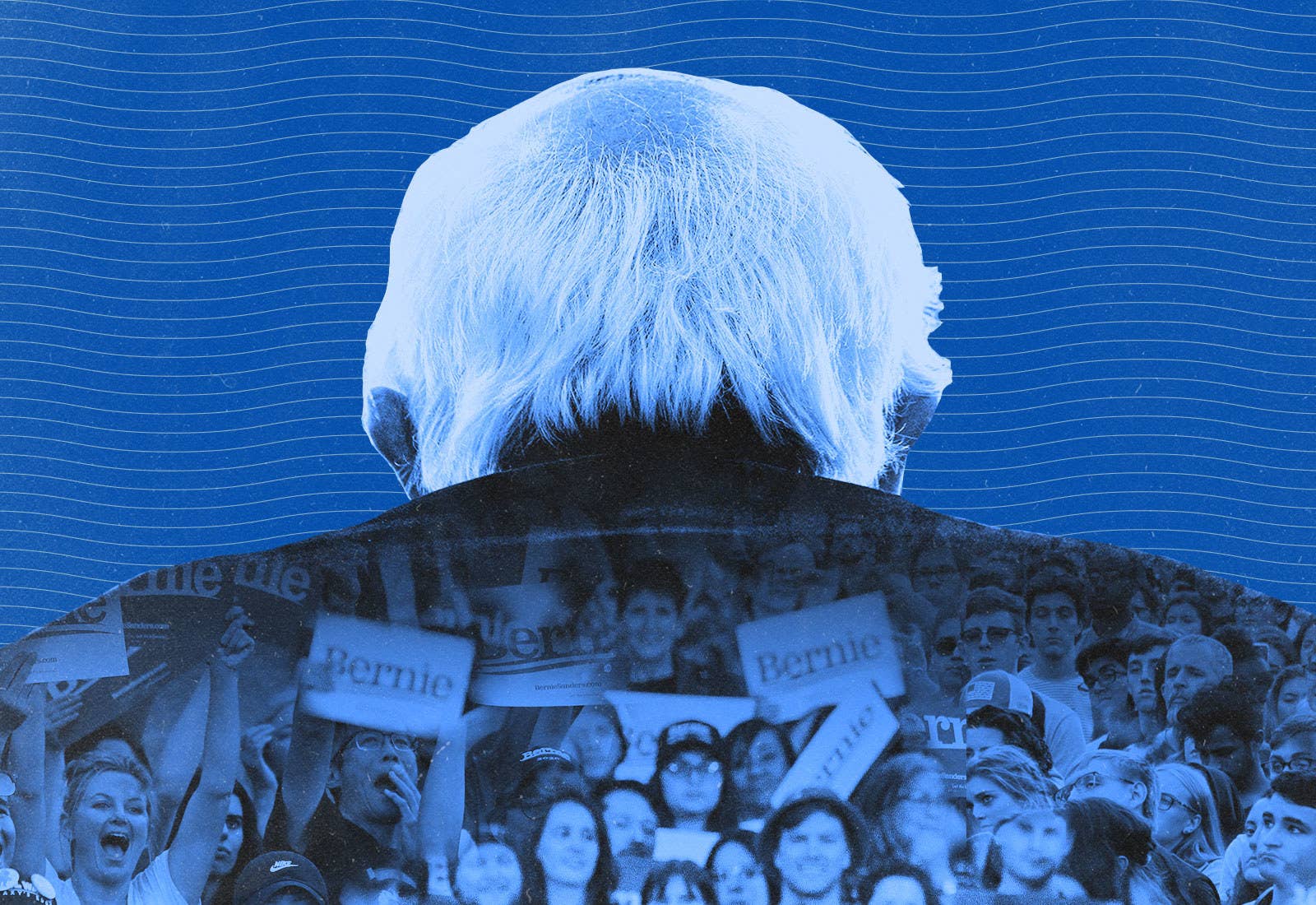

During the Las Vegas Democratic presidential primary debate last month, former mayor Pete Buttigieg — who yesterday dropped out of the race — accused Sen. Bernie Sanders of a failure in leadership when it comes to reigning in his army of supposedly toxic supporters.

“I think you have to accept some responsibility and ask yourself what it is about your campaign in particular that seems to be motivating this behavior more than others,” Buttigieg said.

It was Sen. Elizabeth Warren to whom the question about Bernie Bros was first directed, and to her credit she didn’t opt to smear the diverse coalition of progressive voters working to elect Sanders — likely realizing that they’re potential constituents who value many of the same things she does. Instead, she pivoted to point out who, in her view, was the biggest threat on that stage to Democratic unity and progress: former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg. But for other candidates, the opportunity to pile on the Democratic frontrunner for the actions of his most visibly and vocally aggressive followers — who, granted, probably aren’t Russian bots, as Sanders has insinuated — was too good to pass up.

After Buttigieg got in a few jabs, the Vermont senator pointed out (correctly) that the black women involved in leading his campaign are also victims of “vicious, racist, sexist attacks” from other candidates’ supporters. Though they’d rather not admit it, every single candidate in the race has been able to claim quite a few asshole surrogates and supporters (including Buttigieg!).

It is true, however, that Sanders’ fans — of whom there are many, especially the young and Very Online — are particularly loud on social media. Sanders has wholeheartedly condemned the harassment and bullying carried out in his name since the “Bros” first became a problem for him back in 2016, after which his top aides privately reached out to senior officials at opposing campaigns to apologize for the sexist and racist swarms. Still, by this point, the Bro narrative has been rather exhaustively overhyped, to the extent that the campaign insists it’s become a distraction and a smear.

Particularly because he’s an old white guy — and a cranky one, at that — Sanders is frequently assumed to inspire the worst and most bigoted impulses in the people who support him, regardless of their own race and gender. One Sanders skeptic claims he is “a man who defines himself around his anger, and he attracts a lot of men who define themselves around their anger, many of whom do, in fact, use it as a license to act abusively.” Another explains his rapidly expanding, diversifying base with the theory that “some young women and some young people of color want to be more like angry white men.” Bernie fans who aren’t men must have “internalized misogyny,” this theory goes, while his many supporters of color have “internalized white supremacy.”

When (white male) identity and its resultant “toxic masculinity” is assumed to be the driving force of a candidate’s campaign, it follows that a woman candidate would offer something radically different. Amy Klobuchar, who has reportedly run “a workplace controlled by fear, anger, and shame” in which she “demeaned and berated her staff almost daily, subjecting them to bouts of explosive rage and regular humiliation,” even went so far at the Las Vegas debate as to suggest that we could stop sexism on the internet by nominating a woman for president.

The whole exchange in Vegas perfectly illustrated how a certain brand of neoliberal identity politics, popularized in the Obama era, feels increasingly insufficient to address the most pressing issues of our time. We might all agree, for example, that social media has contributed to the poisoning of our political discourse. But to imply that a woman Democratic nominee in 2020 would stop or even slow sexism (online or otherwise), when Hillary Clinton’s candidacy did nothing of the kind, strikes me as more than a little delusional.

A significant subset of progressive Democrats still cling to the hope that, going into the 2020 elections, presidential identity politics might save us.

Thanks in part to the promotion of marginalized identity representation and visibility in the United States, more women and people of color have leading roles, top jobs, and other positions of power than they did a generation ago — which, proponents argue, means positive trickle-down effects for everybody else. But any feminist or civil rights gains afforded by the efforts and visibility of, say, more women CEOs or queer politicians haven’t necessarily made significant differences in the lives of those on the margins. That isn’t to say power should stay in the hands of old, rich white guys, but that even as the pool of leaders (in everything from entertainment to publishing to politics) has grown slightly more diverse, discrimination and bigotry remain everyday facts of life for millions of Americans. Many nonwhite, nonmale people do make it a priority to raise up others when they ascend to powerful positions, but just as many others pull the ladder up behind them.

Even our first black president, some black activists and thinkers have argued, fueled the false hope of a post-racial era. Critics have pointed out how Barack Obama prioritized a politics of individualized “racial uplift” rather than one of systemic anti-racist change, and received undue celebration from pundits who preferred to overlook the less savory parts of his record “in the name of racial symbolism,” as Cornel West wrote in 2017. Obama’s historic presidency, for all its allegorical power, did not in fact result in a post-racial America — nor did Hillary Clinton’s candidacy solve systemic sexism or stem the tides of gendered violence. But a significant subset of progressive Democrats still cling to the hope that, going into the 2020 elections, presidential identity politics might save us.

I understand the urgency undergirding so much of the push for representation and why, for example, Warren supporters are so heartened by the idea of a smart and organized woman as president, especially since she’s so often been undermined for misogynistic reasons, or why Buttigieg supporters felt passionately that his campaign was a huge symbolic win for queer rights. Both have faced real institutional barriers because of who they are, which can sometimes translate into the belief that, after so much bigoted pushback, it’s simply their turn, regardless of what either of their platforms would mean for the country.

But if anything signals what should be the beginning of the end of identity as a primary metric of candidate selection in Democratic politics, it’s the rise of Sanders and his grassroots, multiracial, intergenerational movement to empower working-class people. For the Brooklyn native and many of his supporters, his identity is beside the point. If Americans elect someone who believes in universal human worth and dignity and refuses to compromise on fundamental issues, then maybe — maybe! — we might actually get closer to something like a "post-identity" reality than we could ever manage through symbolic representation.

One of the latest reported instances of Sanders’ supporters running amok involved attacks against the leaders of the Nevada Culinary Workers Union after they criticized Sanders’ Medicare for All plan, because it would effectively eliminate the union’s hard-won private insurance. Buttigieg mentioned the feud in the Vegas debate, hoping to paint a picture of a Sanders coalition that viciously attacks anyone who doesn’t believe in his platform. But that storyline didn’t stop the senator from dominating the polls; in fact, members of the Culinary Workers Union themselves bucked leadership by backing Sanders in the Nevada primary, contributing to his victory there. According to the New York Times, “many rank-and-file union members said they supported Mr. Sanders precisely because of his health care proposal, explaining that they wanted their friends and relatives to have the same kind of access to care that they have.”

This is something that seems to get overlooked in the focus on the most extreme and aggressive end of a wide spectrum of Bernie stans: Behind so many of his supporters’ vehement anger at unchecked corporate greed is a deeply compassionate impulse of solidarity with other people in this country, regardless of what they have in common and what sets them apart. And that is very much by design; as my colleague Ruby Cramer wrote in December, Sanders is aiming to run “a presidential campaign that brings people out of alienation and into the political process simply by presenting stories where you might recognize some of your own struggles.” So it’s disorienting to watch a parade of supposed political experts and pundits scaremongering about how Sanders’ and his supporters’ rage is divisive, even as he continues to amass a strong multiracial and cross-class coalition.

I don’t think someone who works for the Sanders campaign should be shitposting about opponents, even on a locked account, like former staffer Ben Mora — if only because the senator’s critics are all too ready to pounce on an example of his movement’s supposed toxicity — but I don’t think private insults made by a lower-rung staffer are necessarily newsworthy, either. For one thing, barely a quarter of American adults use Twitter, where a lot of the Bernie Bro hysteria is centralized. And for another, Sanders is reportedly the most-liked candidate in the Democratic field, according to a recent poll from FiveThirtyEight and Ipsos. Most voters, it seems, are comfortable making a distinction between the worst of the so-called Bernie Bros' behavior and the platform of the candidate they support.

I feel similarly about the claims that Sanders is too loud, too angry, too much (which are also leveled, for sexist reasons, against Warren). In Sanders’ case, the accusations carry with them whiffs of anti-Semitism, alongside the troubling insinuation that anger is somehow an inappropriate reaction to the current state of inequality in the US. But they also reflect an attempt to position Sanders as an avatar of the patriarchy.

Projecting individual trauma onto entire communities or movements, made up as they are of an incredibly diverse array of humans, does a disservice to us all.

Sady Doyle, an author and prominent figure from the mid-aughts feminist blogosphere, recently tweeted that she associated Sanders’ yelling with the horrific treatment she endured from her father growing up, and that Bernie’s movement “enacts dynamics of abuse.” Likening Sanders, and, by extension, his supporters, to a violent misogynist becomes a frustratingly self-fulfilling prophecy; a number of cruel and vitriolic responses (which seemingly proved her point) no doubt made it easier for Doyle and others who agree with her to brush off the reasonable, good-faith criticism she also received.

I’d wager Sanders’ supporters are largely aware of the debilitating effects of misogyny, if not experiencing it firsthand. But what overly simplistic readings like “Bernie = Man = Bad” elide is the many complicated ways in which different kinds of people experience gendered violence. Since time immemorial women have terrorized black people of all genders; cis people have terrorized trans people of all genders; the combinations go on and on. Those who feel triggered by the tenor and volume of Sanders’ voice — to the extent that they’d seriously struggle to vote for him over Donald Trump — resonate on the same frequency, to me, as women who’ve experienced male violence and thus refuse to share space with trans women. That’s not to say their trauma is negligible or excusable, but that projecting individual trauma onto entire communities or movements, made up as they are of an incredibly diverse array of humans, does a disservice to us all.

Earlier this year, some similar projection occurred when the question of whether Sanders had privately expressed doubts to Warren that a woman could win the presidency became the topic of public debate. As Natalie Shure wrote for Elle at the time, “the impulse to cast Sanders and his supporters as sexist — intended as a sharp contrast with the feminists behind Warren or Hillary Clinton before her — is based on an analysis of politics as a pop cultural product. In this telling, Warren is the beleaguered underdog heroine, taking on just another old white guy finger-wagging his way to the top. This obfuscates the structural power at work and the degree to which many people are drawn to Sanders’ candidacy for decidedly feminist reasons: In a starkly unequal country with a woefully inadequate welfare state, women disproportionately suffer the harms of poverty.”

Ultimately, Shure wrote, “#MeToo doesn’t urge us to uncritically accept a female presidential contender’s version of a news story; it urges us to take seriously women’s pain and fight for them to have control over their lives — and no one, least of all victims of sexual violence, is served by collapsing that moral distinction.”

To some extent, it’s understandable why Sanders makes such a tempting blank canvas for projecting identity narratives, since the candidate largely refuses to narrativize his identity himself. He doesn’t talk much, for example, about the fact that, if elected, he would be the first Jewish president in US history, though he’s done so more this election cycle than he did back in 2016. (He’s also recently been referring to himself as the “son of an immigrant.”) That’s one of the reasons his recent remarks at a New Hampshire town hall about how his Jewish heritage influences his politics and worldview struck such a chord; a clip of the exchange has been viewed over 1.5 million times.

While other candidates like Warren and Biden “often invite you to consider your story through the lens of their own,” as Cramer wrote in her profile of Sanders late last year, the Vermont senator would rather not use his personal life to connect with voters. “You’re asking about me, and I’M not important,” he once said in an interview. To Cramer, he added, “The gamble is there are millions of working people who don’t vote or consider politics to be relevant to their lives. And it is a gamble to see whether we can bring those people into the political process. One way you do it is to say, ‘You see that guy? He’s YOU. You’re workin’ for $12 an hour, you can’t afford health insurance — so is he. Listen to what he has to say. It’s not Bernie Sanders talking, you know? It’s that guy. Join us.’”

To his supporters, Sanders’ refusal to center himself in his campaign makes it clear that he views himself as a mere vessel for a movement that’s much bigger than one person or one presidency. In many ways, the campaign does traffic in more conventional identity narratives — the focus is just on other people’s identities: those of his campaign staffers and those of potential voting blocs. Surrogates like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez can speak to Sanders’ platform as it’s relevant to different minority communities with personal and cultural specificity, while black campaign leaders like Briahna Joy Gray and Nina Turner emphasize how much of Sanders’ movement is actually shaped by, and for, black women.

Sanders himself is well aware that, on the level of optics, he himself is not an ideal messenger. (At a recent CNN town hall, when asked about a VP pick, he said, “That person will not be an old white guy. That I can say definitively.”) And so the campaign emphasizes the senator’s history of movement ties and support — the people are leading him, rather than the other way around. Were he to become president, Sanders has said he would be acting as “organizer in chief.”

In some ways, of course, Sanders’ universalism with a focus on labor isn’t anything new; every successful presidential candidate has sold the American people on some broader vision, from Obama on hope to Trump on making America great again. And it’s hard to believe anyone vying to become one of the most powerful people on earth when they tell us it’s not really about them. And yet, with the slogan “Not Me, Us” (an active rhetorical reversal of Hillary Clinton’s “I’m With Her”) Sanders has fashioned a campaign built and backed by people of all genders, races, and socioeconomic classes who don’t necessarily see themselves in him as an individual — perhaps because they don’t really need to.

Even though former vice president Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders are old white guys, for example, the former’s overwhelming black support in South Carolina won him his first primary in that state over the weekend; meanwhile, a recent poll shows that the latter has just overtaken Biden in support among African Americans nationally. Of course, at this point, voters are selecting from an all-white field — but even earlier in the race, black voters weren’t necessarily flocking to support black candidates.

Sanders is rarely given representation credit for his ability to speak to people who also know what it’s like to live paycheck to paycheck.

I think often in this never-ending election cycle of Zoe Leonard’s landmark poem, “I Want a President,” written the year I was born. “I want a dyke for president,” Leonard writes. “I want a person with aids for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.” No matter how many times I read it, the poem can still leave me teary-eyed; it’s weighted with so much crushing impossibility.

Because even if we one day do have a “dyke” or a “fag” for president — or a woman, for that matter — it seems impossible that we’ll ever see someone in the White House who truly represents people currently living beneath the poverty line. There have been presidents who grew up in economically precarious situations, and Sanders could potentially join their ranks, but even the sole democratic socialist candidate had to first become a millionaire in order to make it this far.

That’s the strange thing about class. It’s possible to live your whole life in the same socioeconomic bracket — indeed, as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, class ascendance is becoming a rarer feat — but it’s also possible to slip into and out of poverty. Like disability, class isn’t as stable an identity as those of race or gender (though race and gender aren’t necessarily stable either). And like sexual orientation, it’s not always possible to look at someone and determine their family’s present or past household income — which is one of the reasons why, when discussing identity in US politics, Sanders is so rarely given representation credit for his ability to speak to people who also know what it’s like to live paycheck to paycheck.

What’s remarkable about the senator’s campaign is that he drives home the fact almost all of us, save the very rich, are a single medical issue away from complete financial ruin. For all our many differences, this is a grisly reality the working people of this country have in common. Though conservatives and moderates who fear the rise of democratic socialism love to try gotcha-ing Sanders for his “hypocrisy” because he owns a lake house, or target his surrogate Ocasio-Cortez when she wears sparkly tops or gets an expensive haircut, the fact that some people have more disposable income doesn’t preclude them from advocating for a fairer distribution for all. And those of us who’ve managed, against the odds, to ascend from the working poor to the middle class are not under any illusions that being able to buy a nice dress today means we’ll never again have to fear losing our jobs and therefore our health care tomorrow.

Voters who are more progressively minded but still think Sanders’ focus on class is too singular tend to worry his campaign isn’t “intersectional” enough, especially when compared with Warren’s. Last month, the Nation published an opinion piece (since corrected and updated) by professor Suzanna Danuta Walters claiming that Warren is the “first intersectional presidential candidate.” The story includes as examples of Warren’s “intersectional framework” her ability to link gun control to domestic violence, or criminal justice to disability rights. But she’s not the only candidate who can lay claim to a platform that concerns multiple intersecting identities and oppressions. Sanders’ plan for a Green New Deal, for example, prioritizes “Justice for frontline communities — especially under-resourced groups, communities of color, Native Americans, people with disabilities, children and the elderly — to recover from, and prepare for, the climate impacts.”

And if some people are claiming Sanders can't serve the interests of multiple different identity groups or communities he doesn't belong to, a lot of the people in those communities beg to differ. Barbara Smith — who along with other members of the black women–helmed Combahee River Collective coined the term “identity politics” — expressed dismay earlier this year in the Guardian that she so often sees “support for identity politics and intersectionality reduced to buzzwords.” Smith was writing to endorse Sanders for president: “because I believe that his campaign and his understanding of politics complements the priorities that women of color defined decades ago.”

Smith directly addresses the intersectionality concern: “Some critics have questioned whether Sanders is concerned about the specific ways that people with varying intersecting identities experience oppression. As a black lesbian feminist who has been out since the mid-1970s, I believe that, among all the candidates, his leadership offers us the best chance to eradicate the unique injustices that marginalized groups in America endure.”

Critic Andrea Long Chu, in response to the Nation’s piece about Warren’s supposed intersectionality, nailed in a Twitter thread what’s so frustrating about assumptions that Sanders isn’t as strong on issues of race and gender: The piece, she wrote, is “v specific to academic feminists who have so convinced themselves that universalism is a luxury of the elite that when a candidate amasses a broad working class coalition with universal rhetoric their brains pop. … like do i think bernie sanders really knows what a trans person is? no. nor for that matter does liz warren. but trans people need health care way more than they need some politician to give them a nice vibe. … there’s real humility to universalism insofar as it doesn’t predicate public goods on visibility or representation. Bernie doesn’t have to ‘see’ you in order to defend you. it’s impersonal in a way i find respectful.”

Where critics of Sanders find evidence of potential erasure in his universalist appeals — that any moment he discusses the working class in general is a moment when he’s not specifically addressing the concerns of black women or mothers or trans people — his supporters see a radical and widespread commitment to economic justice regardless of who they are.

All of this is not to say identity can’t, or shouldn’t, play any role in an individual politician’s narrative. Sanders, even if his personal life remains his campaign’s B plot at best, still has the power to connect with voters by speaking to his Jewish identity and his upbringing in a rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment. Ocasio-Cortez, too, has made a powerful case for issues she cares about, like a $15 minimum wage, by couching political discussions in her experience as a waiter and a member of the working class. And Warren, in the last two primary debates, has proven to be a formidable Bloomberg opponent by brilliantly connecting her own ordeals of discrimination in the workplace to the indignities allegedly suffered by women under Bloomberg’s employ. She pushed him to release three women from their NDAs in a matter of days. Warren quoting on national TV the horrible things Bloomberg has reportedly said about women made a very strong case for electing someone who intimately understands what it feels like to be harassed, belittled, and violated due to one’s gender.

Attempts to politicize the personal can just as often be a liability as they are an advantage.

But Warren’s candidacy has also shown us the downsides to an overreliance on identity narratives. More than 200 Cherokees and other Native Americans just signed a letter urging Warren to fully retract her dubious past claims to Native heritage, including her reliance on a DNA test that she publicized last year. Warren has previously apologized, and recently reiterated those apologies in a 12-page letter, but the claims continue to haunt her. Neither is relying on the identity of high-powered surrogates a safe bet; the New York Times, in a recent story about how Warren is winning black activists but losing the black vote, Astead W. Herndon reported that “the progressive activists who have showered her candidacy with validation have a different electoral lens than the black electorate at large. That schism is a distinction some have labeled ‘grass tops vs. the grass roots’ — or the belief that the leaders of liberal and progressive organizations have a different political lens than their more working-class members.”

Which is all to say that attempts to politicize the personal can just as often be a liability as they are an advantage — a risky game that Sanders, in his refusal to frame his campaign around his identity, has largely decided not to play.

As a straight white man, even a socialist Jewish one, that’s without a doubt in part a function of his privilege. Most nonwhite, nonmale candidates don’t have the option of making a campaign Not All About Them. Sanders — for all that the Democratic establishment might be doing to try to prevent him from clinching the nomination — does benefit from looking like the “default” political candidate in a way a black person or a woman simply doesn’t. But if you have a built-in strategic advantage in building this kind of universalist campaign, you might as well use it.

Earlier this year, the publishing world’s equivalent of the identity politics debate centered on the novel American Dirt, about a mother and her son fleeing violence in Mexico for the promise of the US. The book, which was criticized for its harmful stereotypes of Latinx immigrants, was written by a woman who until recently identified as white. In a Twitter thread in the wake of the controversy, writer Kaitlyn Greenidge posed an excellent question: “What if the aim of your art is not to humanize the other but to talk about the systems of power, and the ppl who benefit from them, that turn people into others in the first place? Like what if you asked your audience to take it for granted that someone poorer than them is also human and then moved on from there.”

I wonder if Sanders’ campaign might be employing something similar: taking for granted the fact that all of us, regardless of our race or gender or socioeconomic status, are human, and therefore deserving of certain rights: clean water, a roof over our heads, freedom from crippling college debt, medical care that won’t sink us into bankruptcy.

Sanders, like any politician, is not a saint or a savior. To many of those who harbor serious doubts about the fundamental value of electoral politics and the structures that govern our society, a vote for him at the end of the day is still harm reduction, still a way in which we are choosing our enemy. And universalism, at its most basic level, is the biggest cliché in the political handbook: We are all more alike than we are different. But anyone still clinging to the hope of identity representation might do well to remember that. ●